‘Upstairs’ is the pivotal poem in my collection Distance. Six years ago, illness forced my mother to live, sleep and eat in the downstairs part of the house. This was the inspiration for ‘Upstairs’. My original intention was to highlight how, in old age, we slowly lose the world we created. But to write it I had to make some major decisions as a poet. The first was whether or not to write the poem at all. The subject matter was almost impossible to handle without criticism from one quarter or another. The second was to surrender myself to the poem, to go where the poem wanted to go and leave my own prejudices behind. ‘Upstairs’ took me far away from the type of poetry I had written up to that point. And, for the first time, I began to believe that I might be a real poet.

If landscape can recall a personal history, as it did for Seamus Heaney, then an object can also be imbued with memory. In ‘Upstairs’, I use an object-as-memory scenario when the mother asks her son to wear his father’s Alpaca overcoat, so that she might reclaim the memory of her dead husband.

The structure in ‘Upstairs’ is a central part of the poem and the driving force behind it. In the poem, after setting the scene, I wanted to represent a childlike pleading from the mother figure, so I repeated the word “Danny” – in the lines – ‘It was then she called me Danny too many times Danny she called me. / ‘Please, Danny,’ she said.’ As every parent knows, this pleading without pause (or commas in this case) can be very effective. The use of this paregmenon set the basic foundation of the poem, satisfying for both its storytelling and aural properties. I had found the rhythm of the poem.

‘My father was my age when he died / I look like him everyone says I look SO like him everyone says.’ I used double capitals in the word “SO” and repeated “everyone says” to bring home the fact that this was probably a true but tired observation. This allows the narrator to be closely identified with his father. And then, when he puts on the coat, taking on the persona of the father, it seems almost natural. Psychologists can explain how wearing clothes affects the brain and the way we see the world. But in this instance, my reason for having the son wear the father’s coat was physical, to achieve the outward appearance of the father and make real, as far as possible, the fantasy of the mother.

This led to the first of many hurdles; was it likely that a son would put on his father’s coat to please his mother, who seemed to be suffering some form of dementia? Given the fraught nature of the situation, the physical and pathetic circumstances, I’m not sure what anyone might do. In any case I decided that whatever I thought the son might or might not do didn’t matter. The poem wanted to the son to wear the coat and bring the mother upstairs.

So I lift her in my arms. So light. Oh! Sarah you are SO light. I carry her.

Up. To the age before one is old.

Up where Sarah and Danny once moved in the fluid

Of young bodies and slept, hot to the touch.

His mother wants to sleep one more time: ‘Upstairs, where her body will not take her.’ The son brings her upstairs and there is the reiteration of SO again for echo, emphasis and rhythm

Inside a poem we can create complex personalities, conflict, compassion and search for human understanding; outside we try to remain untouched. But all of our constructs must work towards the ultimate need of the poem to be good poetry. In this light, it is not surprising that some poets see themselves as merely a tool the poem uses to produce itself. In a letter to Richard Woodhouse in 1818, the poet John Keats wrote: “A poet is the most unpoetical of any-thing in existence; because he has no Identity.”

I could never support Keats’s contention that poets are merely conduits of the imaginative process and have no identity of their own. My poetry has helped me to build my identity – one poem at a time.

Upstairs

Lying on the bed with my mother,

Wearing my father’s Alpaca overcoat.

Here, Upstairs, where the air is old

And the blue-painted radiators are singing

And the cold cream is liquefying on the dressing table.

My mother can no longer take the cold.

My father was my age when he died.

I look like him everyone says I look SO like him everyone says.

I had to think when she asked me to wear the coat,

For a moment I had to think about it like I didn’t know what she meant.

It was then she called me Danny too many times Danny she called me.

‘Please, Danny,’ she said.

So I put on the coat.

She wants to lie down the pain for a moment, just for a moment,

On to the pink candlewick spread, Upstairs, where her body will not take her.

So I lift her in my arms. So light. Oh! Sarah you are SO light. I carry her.

Up. To the age before one is old.

Up where Sarah and Danny once moved in the fluid

Of young bodies and slept, hot to the touch.

We pretend to sleep, Danny and me,

Though I sweat in the coat and I don’t feel well.

But I stay still, still for Sarah’s sake I am still.

The afternoon seagulls are mad at something in the garden.

I should investigate because they sound so near and real and mad but I can’t

Because she will not let go of his hand.

After a while, released into the darkness, I get up.

I see very little by the nibbling light of the Sacred Heart.

‘Sarah.’ Softly.

‘Sarah.’ Quietly.

‘Sarah.’ My father’s voice.

And she says nothing she says, nothing.

Leaving me, afraid

That everything might be said and done and said

And she has taken all the cold of the earth into herself.

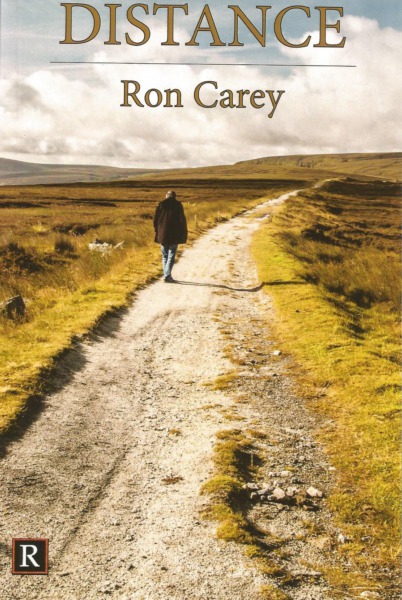

Ron Carey was born in Limerick and now lives in Dublin. He has been a prize winner and finalist in many international poetry competitions including, The Bridport Prize, Lightship International Poetry Prize and the Fish International Poetry Prize. In 2015 he was awarded an MPhil in Creative Writing from USW. His debut collection DISTANCE (Revival Press, November 2015) is shortlisted for the Forward Prize’s Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.