I began the poems in Disko Bay during a midwinter residency at Upernavik Museum in Greenland. My brief was to write about the history of the island and its present-day community but I hoped to record some observations on the wider Arctic environment too. However, the weather conditions were so extreme I couldn’t walk much further than the hilltop cemetery, where coffins decorated with plastic wreaths were lined up in rows, waiting for the earth to unfreeze the following spring. This was a place I visited often while taking a break from writing.

In the museum I encountered many different historical narratives, and began to consider the ways in which the past had been remembered and reinterpreted in Greenland. I read about the earliest settlers, and the perilous sea crossings they had made. Their lives were difficult, and often violent. In one settlement a man who went out of his mind was pinioned under rocks on the summit of the mountain, and left there to die. The horror of this stayed with me, and I often thought about this early ‘burial’ as I took my claustrophobic cemetery walk.

As the weeks went by, and the snowdrifts rose higher around my wooden cabin, my drafts began forming into sonnets, sestinas and ballads. I’d recently been a student on Mimi Khalvati’s year-long Poetry School course ‘Versification’ – a revelation – and I’d got into the habit of writing formal poems. The discipline of form was a deliberate choice now, as it gave me a means to express the austere Arctic landscape and what I perceived as a human tendency towards constraint and cruelty. It was also a way to pay homage to the importance of song in Greenlandic literature.

The man trapped under rocks became the central motif of ‘The survivors’, the first in a series of pantoums about the history of Upernavik. I chose the pantoum because its lines repeat, so that the reader re-encounters the same phrases in new contexts – just as events can be seen to repeat themselves across history, or the consequences of one action may echo through time. Colonisation plays a big part in the pantoum’s story: it is derived from the pantun, a Malay verse form that was introduced to Europe by French poets in the nineteenth century. It seemed a fitting form to consider the colonisation of Greenland and its consequences.

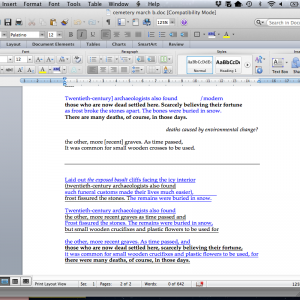

It took many drafts to get the repeating lines to weave satisfactorily through each stanza. The poem was like a Rubik’s Cube: I would solve a conundrum in one place only to find a line had slipped out of sync elsewhere. To keep track of the process, after early notes on paper I moved to a Word document and identified the lines with different colours.

I took the liberty of varying some lines the second time they came around, for example ‘the winter was their warder. Snow blew over the bones’ repeats as ‘the winter, their warder. Wind blew between the stones’. I wanted these riffs on rhythm and content to keep the reader on their toes, and prevent the pantoum from sounding overly mechanical – a common problem with this form.

Despite the pantoum having five stanzas, all those repeating lines restrict you to how many different things you can address. My final version of ‘The survivors’ left out many elements that had initially seemed central – the archaeologists (see draft 1) disappeared from the poem altogether. I also lost the contrast I’d hoped to create with modern-day hospitality on the island: ‘doors were kept unlocked and people walked into other people’s houses’. Eventually even the cemetery of the title vanished, but made its way into another poem in the collection, ‘The hunter’s wife becomes the sun’.

- Notebook

- Draft 1

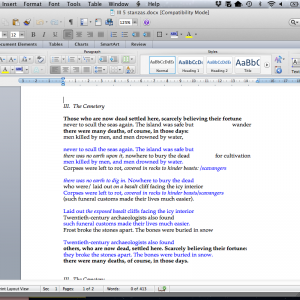

- Draft 2

An early version of the poem was published in Ink, Sweat and Tears. It’s almost there, but still uses the working title. The ‘mad men’ would later become ‘our sons’ (‘mad men’ was rather reductive – and now reminiscent of the TV programme). ‘Young men’ became ‘firstborn’, to suggest a more specific hope. But the crucial change was just one letter, the addition of ‘a’ in the last line: ‘crying for a death to deliver us from darkness’. My intention was that, rather than suggesting the escape offered by suicide, this should have an undertone of human sacrifice (which archaeologists suggest occurred in prehistoric Greenland) – and also anticipate the arrival of Christian missionaries on the island in the 19th century.

It’s good to have a deadline. My obligation to produce work for the museum during my time on Upernavik meant these poems had to be written. But that wasn’t the only incentive. Jackie Kay has said: ‘I think the acknowledgment of the closeness of life to death is often the catapult that makes a writer write.’ My journey to Upernavik through winter storms had been a terrifying one, and I wasn’t convinced I’d ever make it back home. Perhaps ‘The survivors’ grew out of my own fear that I would not survive.

The survivors

We settled here, scarcely believing our fortune

no more to scull the seas. The island was safe but

there were many deaths: driven by the darkness

men killed their kin; others drowned in shallow water

before they could reach the sea. The island was safe but

there was no earth to cultivate, nowhere to bury those men

killed by their kin. Bodies float in shallow water.

Corpses were left to rot, covered in rocks to hinder beasts:

there was no earth to hold them. Where could we hide the dead

when our sons were buried alive on the barren rock?

They were left to die, smothered in stones to keep them still;

the winter was their warder. Snow blew over the bones

of the firstborn buried alive on the highest rock.

The ice on those cairns was as good as a key in a lock:

the winter, their warder. Wind blew between the stones

and if sometimes it sounded like a child crying to be free

the ice on each cairn was as good as a key in a lock.

And so we settled, scarcely believing our fortune,

although it might sound as if we were crying to be free,

crying for a death to deliver us from darkness.

Nancy Campbell is an artist and writer who works across disciplines, from poetry and artist’s books to essays and art criticism. Nancy grew up in the Scottish Borders and Northumberland and her work is informed by these landscapes and borderlines. A series of recent residencies with Arctic research institutions has resulted in projects responding to cultural and climate change in polar and marine environments.

Nancy’s work has a wide appeal. She featured as MarieClaire’s ‘Wonder Woman’ (May 2016) for her writing on the environment, and received the Birgit Skiöld Award (2013) for her artist’s book How To Say ‘I Love You’ In Greenlandic: An Arctic Alphabet. Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy described Nancy’s poetry collection Disko Bay, as ‘a beautiful debut from a deft, dangerous and dazzling new poet’. It has been shortlisted for Forward’s Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection 2016. Recent artist’s books include proviso (2015) and Death of a Foster Son (2016).

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.