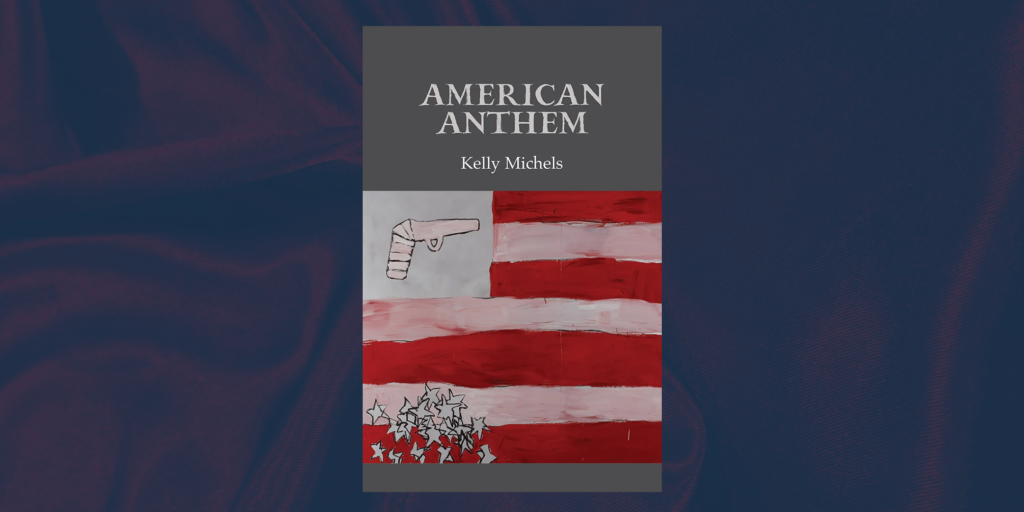

Welcome to our Forward Prizes 2024 ’How I Did It’ series. This year we asked poets shortlisted for the Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection to write about the inspiration behind one of the poems from their chosen collection. Here’s Kelly Michels on what inspired her to write the poem ‘Hurricane Season in Virginia Beach’ from American Anthem.

Hurricane Season in Virginia Beach

She was not a martyr or a quiet saint standing

in the shadows. She did not wear long pastoral

dresses or hang laundry in the breeze like a slow

ballad. She was not the woman with the quake

of trauma in her eyes or a sadness that filled out

her body; she did not know loss or grief or anything

that would make her life more theatrical in its descent.

And he did not hum to Willie Nelson on anonymous

country nights, did not own a rifle or come home

with sawdust on his clothes or a tattoo of Jesus

on his back, knew nothing of deer season

or the sound of Chevy trucks stuttering through dirt lots.

And I did not know the names of wildflowers

or the taste of pig belly, the hereditary maze

of logging roads, did not weave baskets out of corn husks

or tabulate the sorrow of crows in dusty fields.

And she did not soak toast in warm milk and serve it

in a white bowl or remember the time of day

her first child was born, and he did not believe in

aspirin or war or capital punishment. He never raised

his voice to God or to his dead mother, never

questioned the physics of the afterlife, but he knew

how to swim the length of the shore without being

swallowed by birds. And she knew how to tilt

her body through bay windows, knew how to light

a cigarette from the bottom of a toaster,

knew how to untangle a phone cord with her toes,

while I knew what it might be like to kill for love,

knew the names of ocean storms, the yearly parade

of dark bones stumbling through early September.

I knew the dangers of clouds, the grey hiccups of sky

surrounding the moon, the cave of the storm’s

strange silence stunned into light. I knew how love

lived, how it pushed and pulled, how it breathed

in the shape-shifting black holes of their eyes,

in the violence of water, one wave surging

into the next, crashing like the bodies of lovers

tearing at each other, all teeth and scar tissue, nerve fibre

and flesh, plummeting headfirst into the white

soft-spoken shore, as if wanting so desperately

to break the earth and everything on it open.

Beginnings & Negative Space

The initial idea for this poem came from the desire to contend with assumptions, representations, and stereotypes surrounding addiction. Often such assumptions derivative of media representations can devolve into negative stereotypes surrounding class, geography, education, etc. Other associations, such as drugs and rock & roll, can romanticise addiction. And still other assumptions can reside in potential causes for addiction, such as having a harsh or unstable childhood. While some of these conceptions are rooted in reality, none of these apply to my own lived experience with my mother’s addiction. There was no secret abuse or seismic event, for example, that could explain the origins of my mother’s addiction. Instead of overtly working against such representations, assumptions, and/or geographical stereotypes surrounding addiction and the opioid epidemic, I decided to work with them by creating a negative space portrait of my origins in suburbia.

Process & Tone

While a reaction against stereotypes was the primary impulse that began the poem, the writing process unravelled with more complexity once I began working with those stereotypes as an element of craft within the poem. I found myself thinking of the beauty of rural America and the knowledge that comes with being so close to the natural world. As I was writing, I began listing the things I wish I had known – like the names of wildflowers. I wanted to depict some of the magic of rural knowledge so often rooted within a specific landscape. Of course, it is knowledge I too can only imagine through generalisations, romanticisation, and stereotypes because I haven’t lived it. As a result, the tone of the poem becomes something that is not always easily categorisable. Some images evoke uncomfortable stereotypes, some move toward romanticism and lament, and some defiantly lay claim to the speaker’s own physical and emotional landscape.

Metaphor & Hurricanes

This is what I love about the writing process – the poem’s ability to move on its own and lead you to unexpected places. I don’t believe I was thinking about hurricanes when I began the poem. But by listing things I did not know, a portrait of my own origin story began to formulate. While the poem was initially a reaction against stereotypes and categorisations, it ended as a portrait of my parent’s love for each other likened to the intensity and power of a hurricane. Often suburbia can be generalised as a place where nothing much happens, a place that embodies sameness (within its mass production), a place in between rural and urban. However, suburban cities are unique, distinct, and full of intensity. And while I did not grow up around fields of wildflowers, I was well acquainted with hurricanes. This was an element of the landscape I was intimately connected to. This also led me to think about how we categorise hurricanes not by appearance but by intensity, and it became a natural metaphor (and method of categorisation) to explain how I came into the world and how I learned to navigate its unpredictable terrain. It also had the added benefit of creating an ominous tone, foretelling the devastation of what would come later in the collection.

Revision & Form

Originally, the poem was written as a prose poem, but that form did not fit what the poem became. I initially wanted a form that spoke to a need to subvert and/or defy categories and genres. But as a prose poem, it looked and felt like a weight on the page. In contrast, couplets allowed it to move down the page at a faster intensity, freeing the poem from my original conception of it. I had to accept that I had imposed my own confining expectations onto the poem. Categorisation and generalisation are part of the way we all think. The journey of this poem resided in working with this cognitive process as a tool rather than merely working as a reaction against it. Using it as a tool ultimately provided a more fluid dynamic that allowed me to move past (and build beyond) the confines such categorisations can often impose when they become static in the mind.

BIO

Kelly Michels is the author of American Anthem from The Gallery Press which was recently selected for the shortlist for the Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection from the Forward Arts Foundation. She relocated to Ireland from the United States in 2019 and completed her PhD at UCD. Her poems and essays have appeared in Stinging Fly, Poetry Ireland Review, Banshee Lit, Tampa Review, Best New Poets, New Ohio Review, among many others. She previously published two pamphlets, Mother and Child with Flowers (2012) and Disquiet (2015), and her poems have received the Rachel Wetzsteon Poetry Prize from the 92nd Street ‘Y’, the Robert Watson Literary Prize from Greensboro Review, and the Spoon River Poetry Review Editor’s Prize. She lives in Dublin.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.