Here’s Glyn Edwards on his upcoming course, Burning Gaze: Revisiting the Romantics During Global Heating, exploring romanticism and climate crisis poetry.

‘Nearly Daffodils’: BBC6, English Teacher(s), Wordsworth, and Adrian Henri

BBC 6 Music has three playlists; the selection of songs appear on rotation through the day. Sometimes, a song that received intermittent radio play months ago (in that endless June warmth, before the weeks of rain) gains new traction as a band takes their new album on tour, and the ‘earworm’ appears every few hours on the station’s C List. Seemingly, some new singles demand their own encore and rise through the B List to the A List, where they appear in each DJ’s set. It’s the end of November now (my hands have just warmed up after defrosting the car windscreens) and I’ve heard English Teacher’s ‘Nearly Daffodils’ twice already.

Mostly it feels like a waste

So much laughter un-canned

I’d forgotten the taste

Don’t make me go back

All the plans we tiptoed around

In quiet hours, Daffodil buds

There is a reason

The first nine months doesn’t count

(‘Nearly Daffodils’, English Teacher)

It could be the tantalising adverb that initiates the whole narrative, or perhaps the thrill is the song’s unrelenting pace. The addictive element may come from waiting until the chorus, which leaves the final verb hanging throughout, and only completes the lyric with the song’s final word. But, it is probably more that my cognition is hard-wired into making cultural allusions to poetry’s most famous flower. Whenever I hear the word ‘daffodil’, ‘all at once…[t]hey flash upon that inward eye’ (‘I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud’).

Ironically, it was one of my own English teachers that introduced the class to Wordsworth. All too regularly, a hand raised and a voice asked ‘What is iambic tetrameter, Sir?’ The teacher would thump the desk in time to his idiosyncratic version of a poem we all half-knew already: ‘I – wan – dered – lone-ly – on – the -rocks / and – all – I got – was -sog – gy – socks.’ The class would imagine, not the isolated poet remembering a vast sky, the daffodils, but a shoeless form tutor hobbling his four stressed feet along the banks of the Mersey. Perhaps indirectly, he still introduced the central themes the Romantics were concerned with: the fear and beauty evoked by the natural world on the isolated imagination; how we report the sublime affects what others perceive as sublime.

Wordsworth wrote of the early poetic process that helped him to wonder and wander ‘Lonely As a Cloud’ as ‘the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings; it takes its origin from the emotion recollected in tranquillity’ (Lyrical Ballads, ‘Preface’). His poetic style shifted significantly from its natural connection, and audiences in the 1800s preferred ‘Tintern Abbey’ more than they appreciated moralistic insights on the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and liberalism. Perhaps there has been little change in poetic appreciation: in three recent surveys trying to ascertain the nation’s favourite poem, ‘I Wandered Lonely As a Cloud’ has podiumed alongside Frost’s snowy walk and Kipling’s ‘If’ each time.

Very few pieces of art attain a popularity that transcends their maker, and even their genre, entirely. Tourists will hoard around a particular frame in a gallery, but will ignore work by the same artist either side. Most people can name one or two classical musicians, and whether they can remember the name ‘Holst’, they’ll recall hearing ‘The Planets’ in a primary school assembly. In so fondly recalling the daffodils, audiences are seldom challenged by Wordsworth’s radical intentions. In Lives of the Poets, Michael Schmidt writes that Wordsworth ‘questioned poetic convention’, and with ‘a powerful and original vision of nature, developing an inclusive, personal style’ that ‘extended the language and thematic range of English poetry into the new century.’

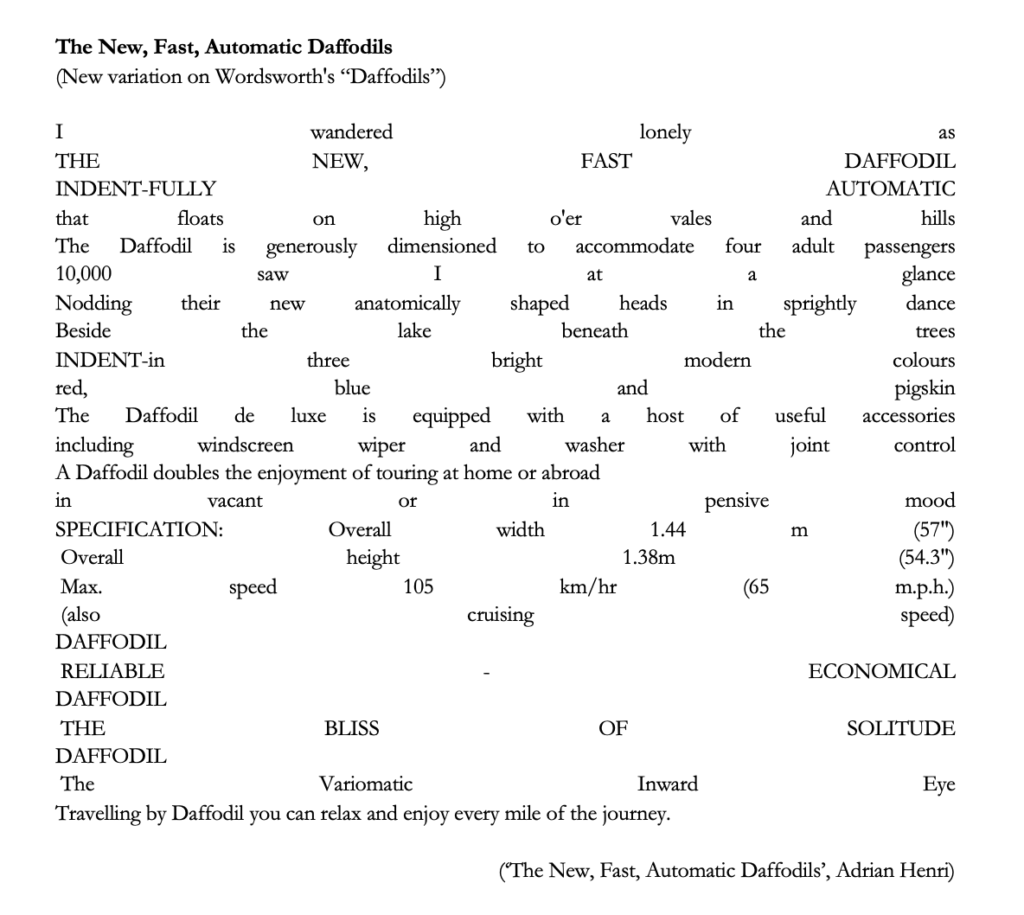

In 1967, Adrian Henri cut-up Wordsworth’s poem and interspersed lines taken from ‘Dutch motor-car leaflet’. The epigraph clarifies the allusion, and the common language of the poem allows Henri to reposition perspective on how ‘Romantic’ ideals are now marketed to fuel consumerism.

Glyn Edwards is teaching our online course, Burning Gaze: Revisiting the Romantics During Global Heating, which consists of 5 fortnightly sessions over 10 weeks and is suitable for UK & International students. This course begins 23 January 2024.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.