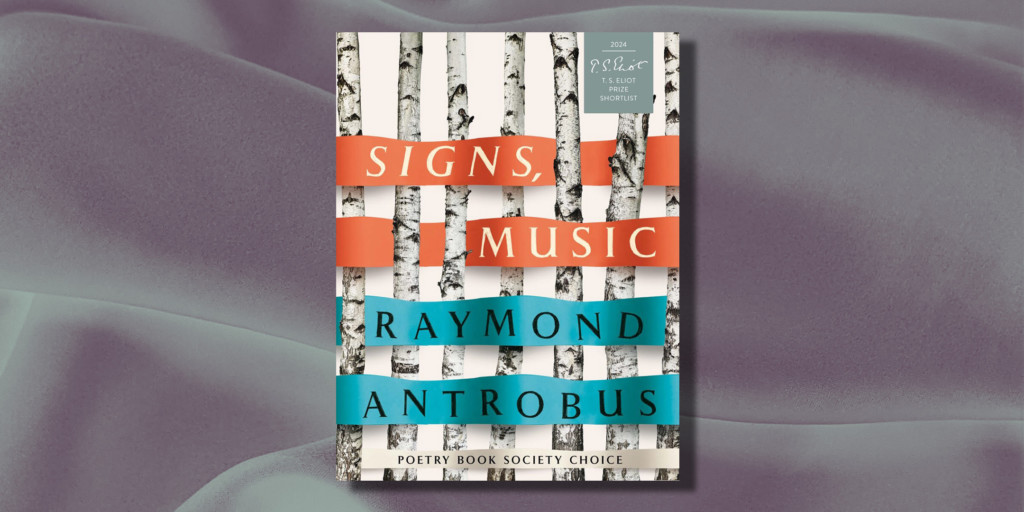

Welcome to our Writers’ Notes for the 2024 T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist. These are educational resources for poets looking to develop their practice and learn from some of contemporary poetry’s most exciting and accomplished voices. Here’s Raymond Antrobus on his collection Signs, Music.

I started writing Signs, Music the week I was told I was going to be a father. I wrote aimlessly, all my usual practice and methods fell away and became something looser. All I knew was I was going to keep writing as an experiment to chart how my writing might change as I became a father. It was an emotional, messy time and my child’s mother and I were running around so much. We were living in Oklahoma and then moved back to London, it was stressful and taxing on both our time and energy, but I was determined to write through it.

Writing Techniques: Wider Networks, First Thoughts…

If I got stuck or unsure about a poem or a phrase, I would send drafted sections to friends, not looking for any detailed feedback. I just wanted to know what worked and what didn’t, what evoked something interesting and what fell flat. I didn’t just send sections to poets either, I sent drafts to friends who work in other art forms – theatre, visual arts, friends whose taste in literature I respect and trust. My network for sounding out bits of poems and drafts was wider than it was for any of my other books. Also, reading! I kept asking for reading recommendations, I kept exploring poetry sections in second hand bookshops. These were all things I could do on the go to keep me feeling like I was living in, and with, the work as I was on the go, preparing a nest for my new family.

It was a very exciting and invigorating time. I wrote lots of stream of consciousness and didn’t just write at desks – I wrote in bed and on buses and trains. Interestingly, most of the material that stayed in the book was written in coffee shops because I was able to feed my poems from the atmosphere and surprise myself. Look, it’s nothing new, it’s literally Alan Ginsberg’s most popular advice, the ‘first thought, best thought’, but the detail that often gets left out of that anecdote is the training and preparation he did before arriving at that first thought. The preparing was looking, listening, phrasemaking, reading the poets in Russia and Ghana… Get outside your orbit and see what you can bring it into it when you arrive at the page – what are the ‘first thoughts’ then?

Kill Those Darlings, Rejoice!

The editorial process was vital, but I have nothing original to add to this either, I’m afraid. The whole finding the Michealangelo in the block of marble analogy is resonant with me for the editing process of Signs, Music in particular. I had enough material for about three poetry collections but had to edit, strip, kill the darlings, carve anything I could away and hope the sequences felt alive, buoyant, and fresh, at least to me. I was so determined to have fun with this book, to actually enjoy writing as much as I enjoyed it when I did it just for me, in private. I think I achieved that. I tightened up some of my line-by-line edits but loosened the container for the overall form, a time-based project. Write one long poem before a life changing event and then write another long poem straight after. It was simple, grounding, and helped that it was overall a joyous event I was capturing.

The Chase…

There is no set text for poetry inspiration for me really. Some of the craft books I devoured that gave me a foundation for writing poetry are The Triggering Town by Richard Hugo, Structure & Surprise: Engaging Poetic Turns by Michael Theune, The Making of A Poem: A Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms by Mark Strand and Eavan Boland, Poetry In The Marking: A Handbook for Writing and Teaching by Ted Hughes and Writing Poems by Peter Sansom. More important however, was reading poetry collections and getting my head round them as reading experiences, understanding image, transitions, enjambments, how to balance high lyric with grounding prose. I am obsessed with these word-based tasks and quests and experiments in ways that I don’t fully understand, but when it flows it is nothing but joy – that’s what I’m chasing every time I write, read, look… hoping for something that shakes me alive.

Energy, Served.

How to know when something is ready? It’s tricky, there are poems that I regret publishing, realising it didn’t quite work and I needed to give more care and attention to it, that perhaps I rushed to publication for the emotional reward factor. I feel much more careful about that now. The poem is ready when the energy that pulled me down to write the poem is served. Sometimes you spend so long on one poem it becomes another poem, which can be fun and interesting, but I’m invested in being guided by a mix of enthusiasm, curiosity, and uncertainty. It’s a tricky balance and we need to be open and patient with ourselves and our work, which has a life of its own, beyond us as the authors.

The Long Game

How to deal with rejection? This is a huge question and I dealt with years of rejection before getting published in print – I was lucky to have people that kept encouraging me to submit poems, even after rejecting them. It took me seven years of sending poems to Poetry Foundation before I got an acceptance and even longer than that to get a poem in The New Yorker. Also, my early books were both rejected by major presses. My first books were self-published pamphlets that I used to tour with. I wrote three short collections and a full collection (The Perseverance) before a major press (Picador Poetry) took me on, which I’m grateful for. But I also came up in a time when the publishing industry was a lot more cynical about so called marginalised literature, poets like Linton Kwesi Johnson, Benjamin Zephaniah, Roger Robinson, Malika Booker (etc.) had to huff and puff at the door so poets like me and my peers could be let in.

It’s a long game. Like I said, there is such a thing as publishing too soon and therefore some rejections are good for us. We need thick skin and discipline. I think teaching poetry to teenagers for seven years in secondary schools and PRUs helped me develop this in many ways, too. In one PRU, I walked into the classroom and was instantly called a “cunt”, but by the end of the lesson, that student did a 180 and ended up having a positive experience with poetry, which wouldn’t have happened if I had let his verbal abuse affect me or taint my expectations of him too soon. Through poetry, we both came away surprised and grateful, and that’s part of what I chase in this art form, too.

The Poetry School and T.S. Eliot Foundation have long collaborated on celebrating the T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist, highlighting this major fixture in the poetry calendar as a fantastic way into the art form and an opportunity to learn from poets at the top of their craft. This year we have a series of Writers’ Notes from the shortlisted poets, alongside a special one-off course with the fabulous Rachel Long, specifically focused on reading and writing after the shortlisted book, Adam by Gboyega Odubanjo. Additionally, we also have an exciting generative workshop exploring the whole shortlist as inspiration for new writing with T.S. Eliot Prize-winner, Joelle Taylor!

Raymond Antrobus was born in London, Hackney to an English mother and Jamaican father. He is the author of To Sweeten Bitter (2017, Out-Spoken Press), The Perseverance (2018, Penned In The Margins / Tin House) All The Names Given (2021, Picador / Tin House) and the children’s picture book Can Bears Ski? (2020, Walkers Books) A number of his poems were added to the UK’s GCSE syllabus in 2022. The BBC Radio 4 documentary Inventions In Sound, which accompanies All The Names Given, was produced by Falling Tree Productions and won a Best Documentary Award at the 2021 Third Coast International Audio Festival.

Thank you for these notes, Raymond. It is very inspiring and also reassuring to learn about the process behind the creation of such a great collection – at least I found out that no magic wand or secret potion was involved!

Given you wrote a lot of the base work for this collection as stream of consciousness, snippets during gaps in time, etc., I wonder how you arrived at the form – form at the collection level, and forms at the poem levels. You wrote that ‘I tightened up some of my line-by-line edits but loosened the container for the overall form, a time-based project’ – it would be great if this point could be expanded. How did you find the shape of the container for the overall form? Did your words and poems get poured flowingly into the container, or did you test pouring into multiple containers before landing on the best-fitting one? Or, was there a lot of stitching and restitching of the words and poems first before you started shaping/looking for the container?