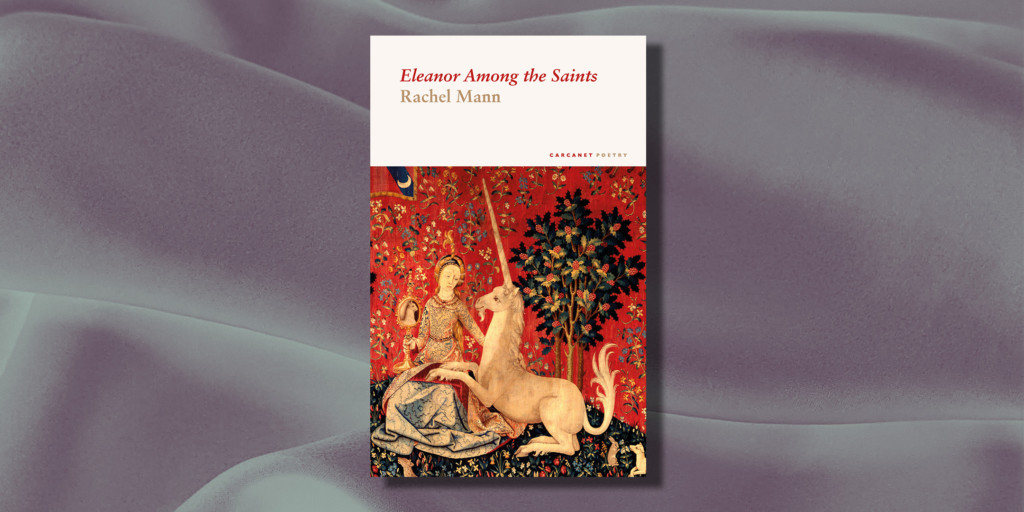

Welcome to our Writers’ Notes for the 2024 T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist. These are educational resources for poets looking to develop their practice and learn from some of contemporary poetry’s most exciting and accomplished voices. Here’s Rachel Mann on her collection Eleanor Among the Saints.

My Writerly Practice? I write to figure out what I want to write. So, writing has been a daily activity for years. Some people go for a daily workout; I have a daily scribble. I become anxious if I am forced to go any length of time without writing, even if that writing is seemingly rambling or even arrant nonsense.

Before Other Realities

These days, I don’t much mind where I write. I used to need a protected space, the clichéd ‘room of my own,’ but a few years ago I accepted that I live mostly in my head anyway. The best way to get out of it and to try and dwell in the world is just crack on and write. At the same time, I have been beyond grateful when I have found a hideaway in which to write. Also, writing in public spaces – on the tube, metro, in a tired-out shopping mall – is liberating, if disconcerting. I like to write in the morning and ideally first thing, before other realities – the basic needs of the day, the day I owe to others – break in.

Finding Eleanor…

The writing of Eleanor Among the Saints began years before it was published. I had a lot of research to do, not least into the historical Eleanor. Perhaps trickier, I had to ‘find’ Eleanor in the poems. I didn’t want the collection to be confessional, that is, merely about me as a trans woman. I needed to test out what it might mean to write through and in Eleanor in such a way that I created space for a reader, without giving too much away or keeping too much back. I find it so tempting to be rhetorical or argumentative when working on a collection. I find characters, masks, and voices helpful ways to avoid that pitfall. Given the many mean things that have been said about trans people being ‘fakers’ or ‘tricksters,’ there is something rather delicious about using devices we’re accused of using nefariously.

Techniques, Tips and Tricks

I try to accept that for extended periods I can barely write a coherent or fresh line. To break out of a rut or a block I commit to two things: firstly, reading as much as I can. I don’t think you can write seriously without serious reading. Secondly, to writing, accepting that much of it will later strike me as feeble.

When I was younger, I’d panic when I sensed I was leaving the ‘sweet spot.’ Now I embrace the departure. Even when things are going well, I no longer fear if much of what I write is inconsistent or messy. Very few of my poems tumble out near complete, in some sort of ‘gift.’ I usually find the poem behind the ‘seeming poem’ in the editing. I think what has killed off some of my poems, or attempted poems, is my intense desire to achieve control and mastery. I need to take the risk of letting go of the words, at least to an extent (!), so that they can speak.

Editorial, Discovery!

I used to think that my obsessive fascination with edits and editing was a token of my lack of skill as a poet. When I was starting out, I figured that proper or good poets were so on top of their writing that they just banged poems out fully formed. Then I saw Elizabeth Bishop’s edits for ‘One Art’ and the penny dropped. To edit (and indeed to be edited by a skilled editor like Michael Schmidt at Carcanet) is not simply refinement, it is the collection’s discovery.

For Inspiration…

Glyn Maxwell’s On Poetry is such a helpful book. Part theory, part storytelling, and part challenge to write better and more sharply. I’ve had the great good fortune of being taught or mentored by some exceptional writers, though I should give a special shout-out to my friend Michael Symmons Roberts who believed in me when I wasn’t sure I could.

I go back to poets like Herbert, Donne and Christina Rossetti a lot. They remind me it’s possible to write poetry which is not destroyed by my faith.

Ready?

Was it Geoffrey Hill who spoke about a poem’s completion as like the clicking shut of a hand-tooled lid on a box? I’ve known that experience. That sense that the artefact is finished, just right, and it is time to step away. Perhaps that experience has become more common as I have grown in confidence, though I am mindful of Auden’s approach which seemed to entail revising published poems pretty much till he died.

On Rejection, and Bullshit Detectors.

What is the point of writing if there is no rejection? Though, I wish it happened less often. One way I cope with rejections is by theorising that they are predicated on attention. That is, someone has read my poems with care, and I need to consider what it is that did not land with them. At the same time, I have been writing long enough to have learned that some poems may be good, even excellent, but they do not land with a particular editor or judge.

There are many poems and collections by excellent poets that I recognise as fantastic, but not really for me. That is okay. One thing I remind myself about is that ultimately my poems are mine, and even when they are crap, they are my crap with their own distinctiveness. That helps me smile. Eleanor Among the Saints lost some poems, as part of my beloved too-and-fro with my editor at Carcanet. Others I argued to keep. There is nothing quite as wonderful as an editor who asks the right questions to make you write better. So often I am trying to pull a ‘lyric fast-one’ for a cheap effect. The best editors are bullshit detectors, and confessors.

The Poetry School and T.S. Eliot Foundation have long collaborated on celebrating the T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist, highlighting this major fixture in the poetry calendar as a fantastic way into the art form and an opportunity to learn from poets at the top of their craft. This year we have a series of Writers’ Notes from the shortlisted poets, alongside a special one-off course with the fabulous Rachel Long, specifically focused on reading and writing after the shortlisted book, Adam by Gboyega Odubanjo. Additionally, we also have an exciting generative workshop exploring the whole shortlist as inspiration for new writing with T.S. Eliot Prize-winner, Joelle Taylor!

Rachel Mann is an Anglican priest, poet, writer and broadcaster. She has written fifteen books, including two collections of poetry. She is Visiting Teaching Fellow in the Manchester Writing School, Man Met University, and she regularly broadcasts on BBC Radio, including as a presenter of Thought For the Day on the Today Programme.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.