As it turns out, this diary-cum-sketchbook may be oblique in form but it’s acute in content, being a moving and skilfully ambivalent tribute to Kang’s senior sister, who ‘died, I was told, less than two hours into life’. The White Book can be considered a kind of ghost story, its narrator haunted by the thought that ‘If you had lived beyond those first few hours, I would not be living now.’ Immediately we see how Kang has done something quite clever – swapped funereal black for spectral white – though there is nothing too artful about the execution. Not at first, anyway: the text begins with some relatively straightforward background on the broader theme’s incubation, during which time the author imagined creating ‘something like white ointment applied to a swelling, like gauze laid over a wound. Something I needed.’

Abandoned only to be taken up again, the idea for a work ostensibly ‘about white things’ compelled Kang to embark on an experimental project of isolation in an unspecified European city, where the people ‘want to draw out their grief for as long as possible’ – just as Kang pursues her own strange grieving process, ‘[stepping] recklessly into time I have not yet lived, into this book I have not yet written.’ It’s worth noting, however, that none of this prologue is separated from the main text. What are we to make of an experiment’s abstract, so to speak, when it seems to be of a piece with the results?

Another question might be: what does this have to do with poetry? I’ve clarified that The White Book is not a novel; indeed, it seems to me that its definition is up for grabs (‘a book like no other’, the publisher insists). It’s prose but not necessarily prosaic, which is to say it conveys not just information but sensation, and its pages’ frail squares of text share the benign solipsism of poems. They stand alone:

The twenty-two-year-old woman lies alone in the house. Saturday morning, with the first frost still clinging to the grass, her twenty-five-year-old husband goes up the mountain with a spade to bury the baby who was born yesterday. The woman’s puffy eyes will not open properly. The various hinges of her body ache, swollen knuckles smart. And then, for the first time, she feels warmth flood into her chest. She sits up, clumsily squeezes her breast. First, a watery, yellowish trickle, then smooth white milk.

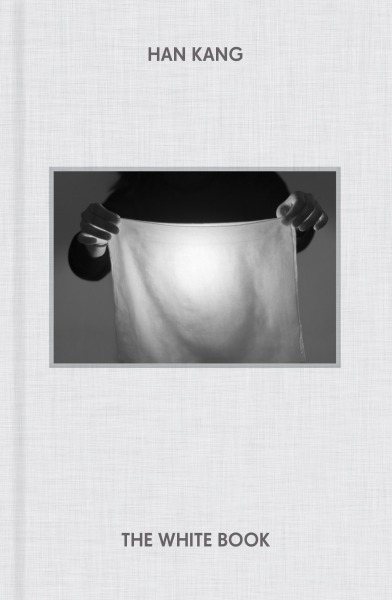

Exemplary translator Deborah Smith seems to have an ear for cadences, occasionally producing lines that could easily pass for verse: ‘Or do they only shake or nod their heads, without the need for words?’ Meanwhile, Choi Jinhyuk’s expertly, sparingly deployed images add to the sense that this is more of an aesthetic exercise than a narrative one, and intentionally so.

At times, however, you will wish the opposite was true: the middle section drags, beginning to feel like a box-ticking exercise getting bogged down in its own premise. Asking ‘Why do white birds move her in a way that other birds do not?’ is one thing, but answering ‘She doesn’t know’ is quite another. One suspects that white birds move her because it is necessary that they do so for the purposes of the book, and to be evasive about it seems disingenuous. But when Kang says what she means and says it forthrightly, she wins your full attention:

There are certain memories which remain inviolate to the ravages of time. And to those of suffering. It is not true that everything is coloured by time and suffering. It is not true that they bring everything to ruin.

Regardless of whether you agree with this sentiment, it is perhaps one of the more rational cases for a belief in ghosts – as memory-entities that are real as long as they preoccupy us. Except Kang can’t remember her sister, because she never met her. Maybe this is where the white comes in, with the artist doing what comes naturally to her by seeing blank canvasses in all things blanc; blank canvasses arrayed for the imprinting of a soul, like particle detectors hoping to capture anti-matter. Thus one of The White Book’s aims is to use art to recover ‘life. Which would have been beauty.’

A related aim, I think, is to explore the idea of the blank slate, or indeed the illusion thereof. Pursuing a kind of redemption, the author repeatedly uses white as a means to neutralise or wipe clean, only to find this isn’t possible. It is ‘A whiteness that [seems] too perfect to be real’, and this empty space has a life of its own:

Finally, I stepped out into the corridor to paint the front door. With each swish of the scar-laced surface, its imperfections were erased. Those deep-gouged numbers disappeared, those rusted bloodstains vanished [but] when I came back out an hour later I saw the paint had run.

Later, she observes how ‘The border between sky and earth has been scrubbed out [and] all else is white. But can we really call it white? That vast, soundless undulation between this world and the next, each cold water molecule formed of drenched black darkness.’ Moments such as these, when The White Book subverts its subject rather than merely presenting it, are some of its strongest. And that divide ‘between this world and the next’ is precisely what Kang’s artistic vigil attempts to bridge, ultimately allowing itself a direct encounter with the author’s imagined older sister (or ‘onni’):

An onni to come over when I’m huddled in the dark. There’s no need for that, it’s all a misunderstanding. A brief, awkward embrace. Get up, for goodness’ sake. Now let’s eat. A cold hand grazing my face. Her shoulders slipping swiftly away.

Is it sentimental? A little, yes, but it’s also necessary. The scene gives the ghost a realised human form, bringing it – and thus the conceit – to completion.

The White Book is a courageous work of poetic meditation. To follow two successful novels with such an experiment might seem an anomaly to fiction lovers, but if it wins Kang new fans in the poetry world or further afield, that’s no bad thing.

Poetry School invites (and pays) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at – [email protected].

You can

You can

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.