Layli Long Soldier’s debut poetry collection, Whereas (Picador) roots through the vocabularies it employs, carefully tracing its linguistic inheritances. Long Soldier is a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation, and is keenly aware of the power – and lack thereof – that language can command.

Whereas is split into two parts. Part I, ‘These Being the Concerns’, sketches an informed consideration of Native heritage through Lakota words, myth, the work of Zitkála Šá; it probes the unreliable relationships between language and meaning. Part II, ‘Whereas’, dismantles the bureaucratic language used in the 2009 ‘Apology to the Native Peoples of the United States’ – exposing its emptiness and inadequacies. Whereas disassembles any pretensions of neutrality that words might have, proving with dizzyingly acute dexterity the politics inherent in all the ways that reality is translated into language.

Long Soldier’s own etymologies come from her position as both a ‘citizen of the United States and an enrolled member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe’. From within this dual heritage, she asks how experiences and traditions are communicated from Lakota into English, and what might be altered in the process. The first poetic sequence in Whereas, ‘Ȟe Sápa’, refers to a mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America. Long Soldier takes care to emphasise to the reader: ‘Remember. Ȟe Sápa is not a black hill, not Pahá Sápa, by any name you call it.’ In an interview for the Kenyon Review, she explains that ‘when the settlers came, they translated ‘Ȟe Sápa’ into English and the place was referred to as ‘Black Hills,’ but our word actually meant ‘mountain’ and not ‘hill.’’ Through this careless translation, the colonial ‘settlers’ enact a linguistic violence upon the Lakota landscape – a diminution from ‘mountain’ to ‘hill’. Language is a battleground; whilst re-wording something frames our conceptions of it, Long Soldier opines that the landscape resists. Out in the world, a mountain ‘by any name’ remains a mountain.

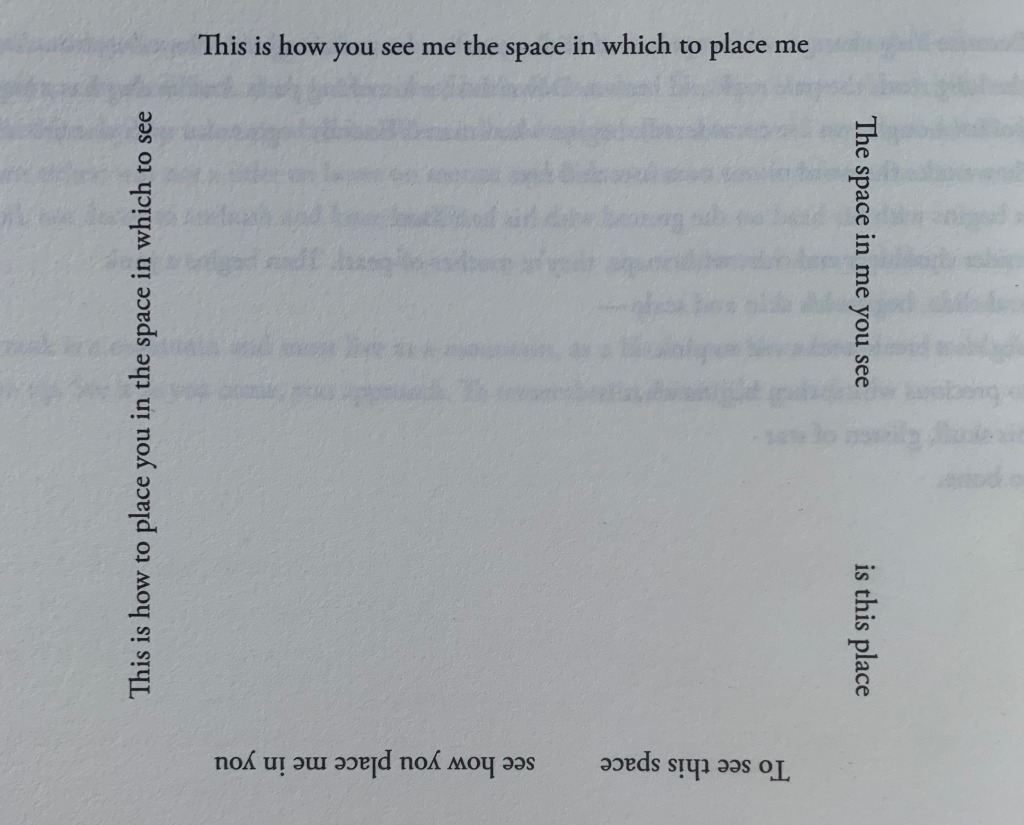

The (re)framing of concepts through language continues in ‘Three’, from the ‘Ȟe Sápa’ sequence. Here, Long Soldier traces a box with text, configuring a square emptiness inside. The phrase ‘This is how you see me the space in which to place me’ is distorted as the construction of the box progresses – and tellingly, as the phrase morphs, it is the repeated ‘me’ that gets lost, until all that remains is ‘This is how to place you in the space in which to see’. By this point, the phrase has stopped making sense. If it can be said that language attempts to constrain identity, Long Soldier’s wry repetitions show the tensions inherent here – does language control the subject, or vice versa?

Language continues to manacle identity in ‘Part II: Whereas’. In the second ‘Whereas Statement’, Long Soldier writes: ‘But the term American Indian parts our conversation like a hollow bloated boat that is not ours that neither my friend nor I want to board, knowing it will never take us anywhere but to rot.’ In these concerns, there is an echo of the boarding schools to which Native American children were exclusively sent in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, to be taught – in English – to assimilate and absorb Euro-American culture. Their native languages were forbidden, and their names replaced with those more familiar to the Christian missionaries who first established these schools. The construction of Native identity to suit a Euro-American perspective in this way is a violent distortion – at once outsize, heavy, ‘bloated’ and entirely meaningless, ‘hollow’. There is nothing hospitable about the language of the oppressors.

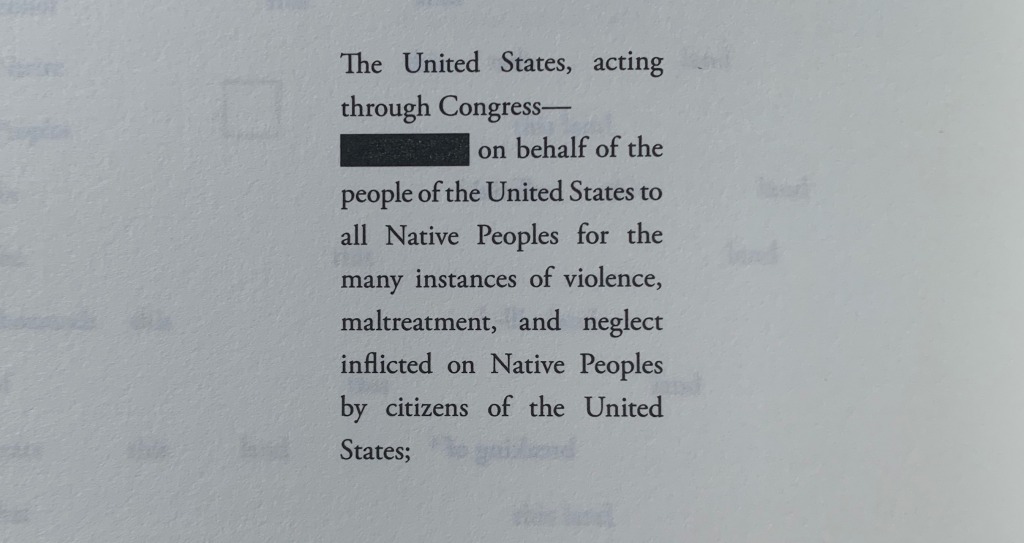

The entire second section of the book is a response to the ‘Congressional Resolution of Apology to Native Americans’ issued by the US government in 2009. It was signed by President Obama but never formally read aloud, and the tribes to whom the apology was ostensibly addressed were not informed in any meaningful way. The apology was buried in an obscure bill under layers of legal language. Is a silent apology, so couched in bureaucracy, really an apology? What does it mean to apologise in a language that doesn’t cater to its addressees?

‘In many Native languages’, explains Long Soldier, ‘there is no word for “apologize.” The same goes for “sorry”. […] Thus, I wonder how, without the word, this text translates as a gesture–’

As a piece of language, the apology proves to be absolutely a ‘hollow bloated boat’. The excessive legal jargon precludes sincerity and by redacting the word ‘apologises’ here – a word that does not even translate to many Native languages – the inadequacies of the ‘gesture’ are thrown into sharp clarity. Rather than describing ‘neglect’ and ‘maltreatment’, would it not be more accurate – more impactful – to speak of genocide, cruelty, theft?

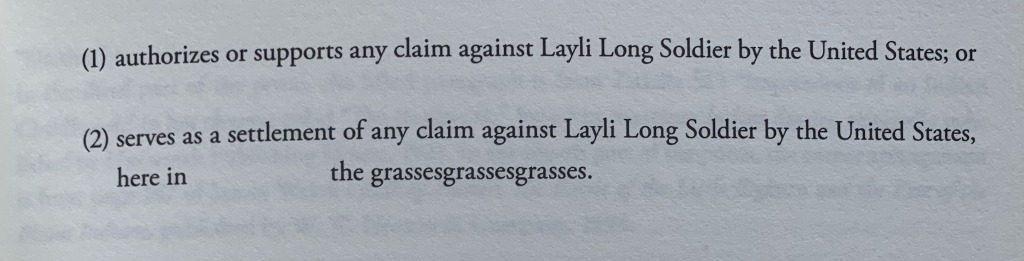

In legal parlance, ‘whereas’ as a preface to a statement means ‘taking into consideration that’. The collection’s focus on this word not only highlights the fluidity of language – how context forces constant shifts in meaning – but also asks, repeatedly, what this legal consideration might entail. The 2009 apology is undermined by a disclaimer that nothing in its contents ‘(1) authorizes or supports any claim against the United States; or (2) serves as a settlement of any claim against the United States.’ Crucially, no real responsibility is being taken here. The language of the apology is crafted to soothe an oppressive conscience; it is not made for the addressee. No reparations are forthcoming. Long Soldier infiltrates this phrasing in her own disclaimer at the end of the collection:

Here, she relocates her book ‘here in the grassesgrassesgrasses’, displacing the legal jargon and emptying it of its power. Taken out of context, the language of the government loses all sense.

In ‘38’, a sequence about the largest mass execution in American history, in which 38 Dakota men were ordered to be killed by President Abraham Lincoln in response to the Sioux Uprising, Long Soldier ruminates on forms of poetic expression that don’t depend on language. She tells the tale of Andrew Myrick, a trader ‘famous for his refusal to provide credit to Dakota people by saying, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.”’. During the Uprising, in which the Dakota people railed against the treaties that forced them to starve, they executed Myrick, and ‘stuffed’ his mouth with grass. She considers the poetic symmetry and repetition in this action:

I am inclined to call this act by the Dakota warriors a poem.

There’s irony in their poem.

There was no text.

“Real” poems do not “really” require words.

By placing ‘real’ in quote marks, Long Soldier implores a questioning of what ‘real’ poems might even entail; in a collection that relentlessly questions the duplicity of language, what are the components of a ‘real poem’? Through the poem, the poet’s processes of thought are laid out on the page. ‘But, on second thought, the words “Let them eat grass” click the gears of the poem into place. / So, we could also say, language and word choice are crucial to the poem’s work.’ Rather than using language to plead neutrality in long, declarative statements, Long Soldier uses it instead to explore the meandering nuances of thought. Nothing in the poem is static.

Throughout Whereas, Layli Long Solider conducts an elegant exposé of language’s deceptions. By manipulating language so skillfully herself, she places herself perfectly to highlight its inadequacies. Although conventions of grammar and legal phrasing give the illusion of logic, neutrality and authority, Long Soldier exposes these constructions as weak. Without sincerity, accuracy or action to ground them, words do nothing. The hill remains a mountain. ‘My tooth will not grow back. The root, gone.’

Buy Whereas by Layli Long Soldier from the Poetry Book Society

If you’d like to review for Poetry School, or submit a publication for review, please contact Will Barrett on [email protected].

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.