I think of myself as pretty much unshockable, but there are, for me, some gasp-worthy moments in this unflinching collection from Alice Anderson.

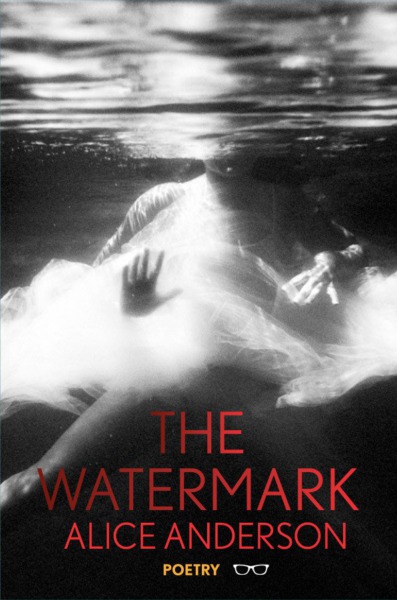

Set in the American South, The Watermark is an apparently confessional book and almost every element of Anderson’s world is refracted through a lens of sex and violence. This is the story of a life blighted by the experience of abuse. But it is also the tale of a survivor, a woman who has endured more than one kind of storm and come out loving and fighting and writing.

The bulk of the book consists of what appear to be personal poems, and these are framed at the start and finish by poems about Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. In the first two poems, both Katrina and then ‘The Quiet’ afterwards are personified as dangerous and sexually rampant women. These set the tone for all that follows. In the opening poem, ‘The Water’ Anderson writes of the hurricane:

She engulfs you like an orgasm that

won’t ever quit, her wet excess

going and going and going

And at the close:

She comes in and takes you like a lover, swift and fierce

and seemingly devoted,

and takes all your money and your children

when she goes.

The second poem, ‘The Quiet’, personifies the quiet on day after the storm as a different, but equally destructive woman. Here, in sinuous lines of free verse, Anderson achieves some startling feats of imagery and imagination:

… The quiet leaks warm milky rivulets on

the mourning mother’s borrowed dress. She’s there in the eyes of the

sister, she’s there in the frost of the morgue.

And at the end:

The quiet is your unrequited lover, come finally

to take you: a gun to your throat, a diamond ring

in her mouth. She locks your thighs in her ghastly grip,

and never stops kissing you while she fucks.

These two juxtaposed couplets demonstrate two competing aspects of Anderson’s poetry. The first sentence is imaginative, surprising and beautifully devastating, while the closing one goes too far for my taste, with the adjective ‘ghastly’ attached to ‘grip’ and the ‘while she fucks’ at the end, just putting the metaphorical boot in a little too emphatically. It would be easy to overlook the subtler moments (of which there are many) in this courageous collection, letting them be drowned out by the louder ones.

Here you will find not just first person tales of childhood abuse at the hands of her father, but also other disturbing and violent episodes located in the Deep South. There is a strong narrative streak to much of work: one poem, ‘The Season of Ordinary things’, tells the tale of a mother who kills two of her children in what seems to be a religious psychotic frenzy. Another, ‘Joy Ride’, is a free verse poem in the second person, cast in long lines.

Anderson likes couplets and often, as in ‘Joy Ride’, the line breaks are not clausal and fall on prepositions or pronouns, creating a sensation of teetering on the brink of something, almost of falling. The stanza breaks themselves are frequently enjambed as if the pauses are for breath rather than meaning. ‘Joy Ride’ is based on a newspaper headline and is from the point of view a teenage boy who takes his father’s car for a drive and, on arriving home, is beaten (probably to death) by his father:

… You see your father: he’s waiting at the table when you

slip in, set down the keys he picks up and slashes into your face. You take in

a sharp breath and think: Night air. The sun turns from pink to white seeping into

every corner of the panelled room, you taste salt in your mouth and think rough

water on the Gulf. And when the bone of your arm splinters like old kindling

stomped on in the yard, the sound is like a word whispered luck.

Many of these poems have the appearance of autobiography and one long, central poem, ‘Hush’, told in quatrains, ballad style, with some subtle and loose rhymes, is written in a dissociated second person voice. This distancing effect is useful in digesting the material, an account of sexual abuse at the hands of her father and the strategies she as a child uses to try and avoid him, ultimately without success:

You are sound asleep in bed, dreaming

of the bayou, only silence

and a pair of red-headed

woodpeckers to share

your picnic. In the dream there is

a panic of wings, of woodchips

falling, of air too heavy for flight.

You’re pinned.

You wake, see him hovering, your

Door shut tight,

Nightgown and covers thrown

to the floor

‘Hush’ pairs with ‘Disgrace Aria’, a long poem written in sections with its shocking anaphora : ‘I’m five years old – I’m sexy.’, and its refrain ‘Shame on you.’ In this startlingly titled poem we see the child taking back some power the only way she knows how, and although it seems to depict the child as victim: ‘I’m five years old. I’m sexy. / I can take it down the throat / so much easier since the surgery’. It goes on like this:

…and when daddy

comes in and one night I’m

waiting, I got

no clothes on, I got my lips

painted red, I got my pointe shoes

laced up super tight. I’m in the middle

of the moonlight on my toes and I go

“C’mon Daddy, c’mon, Now

you ready to do me right?”

And I guess I’m getting

too old or maybe I’m

not sexy ‘cause he just

turns red and

turns around and

marches out the door.

‘The Love Brigade’, a long, thin, relentless poem without stanza breaks continues this theme of sexual domination and submission. Here, Anderson recounts her experience of sex with a partner who shares her history of damage and abuse:

…We don’t know what it

means to feel clean. We are welted skin

smeared with memory and

forgetting-mud, we are behind

the closed door, we are the endless

night, the two hours when mama

goes to town, we are the come around

to wanting it, we are the pact

we made with the ones that fucked

the baby-good out of us.

I ask you to hit me.

You beg me for

A safe word. I tell you nothing

is safe…

Indeed, nothing is safe in this book, including love and motherhood. Even in ‘To the Wolves’, a poem that shares some information about her children and family her life as a mother is mediated by the experience of giving birth to still-born twins:

…I prepared your room, – took out the second crib and

brought in a big leather rocking chair, imagined sitting

there, nursing you, looking out on the hundred yards of bayou

emptying into salty, wide open gulf, the waters merging,

the creatures staying mainly to one side, the other.

I have three healthy babies, I said again, not realizing

my husband stood in the closet not three feet away.

From behind the door: Get over it.

As the title suggests, water is a recurring image in this deepest of Deep South landscapes with its bayous, swamps and hurricanes constantly posing the threat of disaster. Interestingly, the title poem, which is also the last one, offers a glimpse of redemption. It is set in a shelter three days after the storm and ends with the image of a young girl, a survivor, a ‘possibility in a ravaged dress’, who is an avatar for Anderson herself:

… There is a girl, a sort of ordinary girl, pretty

in a way you think of a pattern of cheap duct tape stuck

to a wall after a makeshift sign has fallen is pretty, found

art, eyes black as midnight, freckles either God-given

skin starlight or simply splattered mud, in her fragile communion

dress edged in Irish lace, Social Security number still scrawled

in Sharpie on the alabaster underside of her arm

in her father’s slanted hand. And on her dress: a

meridian, smack dab across the middle of her sunken chest,

right where her frenzied swimming heart nearly

drowned, but was baptized by fire instead, a spare but

graced rebirth. This almost lovely, scrappy girl, possibility

in a ravaged dress, catastrophe spelled out in seed

beads and sequins, alive, above the watermark.

In fact, most of the characters, both literal and metaphorical, who pass through this book, could stand for the author.

Anderson’s work is, as they say, not for the faint-hearted, it doesn’t pull its punches and sometimes, perhaps in an effort to be brutally honest, punches a little too hard. But ultimately it is a direct and gut-wrenching collection, one that will stay with you long after you’ve read it. If you take your poetry strong and dark, this one is for you.

Reviews are a new initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at – [email protected].

You can

You can

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.