Rishi Dastidar’s second collection is a chimera. At once a long narrative poem, a one-man play with modest stage directions, and a DIY manual for How to Set Up and Rule a Nation, the book is also written in the format of a legislative document, with numbered clauses sub-dividing into indented elaborations:

24.2. It was well past time you took a bit of freedom

24.2.1. for you.

24.3. Because if you didn’t

24.3.1. no one else would do it for you.

And then, over the page: ‘He takes his crown off his head. He worries it around his fingers.’ More on this crown forthwith.

From the offset, the premise is dense: the text offered is the script for an address to an audience, the role of speaker or spoken-to can be assumed at will; this ‘you’ bounces between an address to the self or to others — is this a one-man show happening in the dark, speaking to itself? Is anyone even listening? And then there’s the legislative element: is this a constitution being drafted in real time? The answer is: sort of.

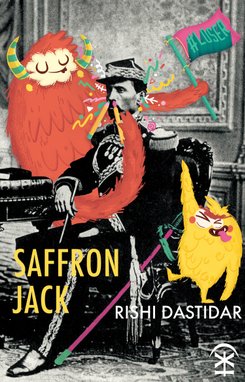

Drawing upon The Man Who Would be King (both the 1888 Kipling novella and John Huston’s 1975 film adaptation, as Dastidar informs us in the notes), Saffron Jack is a record of establishing a ‘heimat for one’, a country when other countries have failed, and making oneself its king. Huston’s The Man Who Would be King depicts two white British ex-soldiers who have become disillusioned with Victorian India, deeming it too regularised (‘regularisation’ that they, as agents of the British state, have helped to bring about), so they set off into remote Afghanistan in hopes of finding some people they can convince to crown them. It’s a story of lovable rogues meeting gory ends at the hands of inarticulate hill tribes; a jolly jape in the sub-continent when ‘the sub-continent was ours – / 61.2. no, theirs – / 61.2.1. to be jollied’.

Crucially, Dastidar’s poem deals in discomfiting questions about the nature of this ‘our’: is the brown British narrator of Saffron Jack, even with his ‘glottal stop’ and ‘lack of facial hair’, a true stakeholder in the common wealth of Britain? In contrast to the protagonists of The Man Who Would Be King, the wannabe king of Saffron Jack wants his ‘imaginary land of luxury and idleness’ as an escape from a racist Britain which will not have him. He is equipped with a ‘cheap shit, £9.99 crown from Argos’ and a flag, the Saffron Jack of the title: a ‘remix[ed]’ Union Jack, ‘spiced up a little’ in bright colours. The comedic departure point, however, hides much more sombre motivations.

Dastidar’s would-be king lists the ingredients for successful nation-making: if invading, your war will not just ‘need the mindlessly brave; / 84.2.1. it wants the cunningly cowardly too’, and a ‘caché of weapons’, where ‘caché’ flickers fantastically between a cache of weapons (as guerrilla fighters, part of an insurgency, might possess), and the cachet conferred by an army. The use of the word ‘caché’, here, is a stroke of genius, encapsulating, as it does, all the difficulties of conferring legitimacy on the struggle for self-determination: how many weapons do you have, and are they provided by taxpayer money? If not, forget it. The rulebook of passport design is also ripped up with the offer of ‘Vouchers! Gift cards! … Two for one entry into the country, and what the hell, you’ll chuck in a chicken tikka masala too!’. This rambunctiously all-embracing, coupon-code, bargain bin attitude to immigration functions as a scathing critique of the British Home Office’s ethnonationalist model, where immigration legislation favours the rich.

Countries must also be founded in opposition to something, that is in their very nature (to have edges, and things which abut them) – all the better if they can be predicated on a narrative of persecution. To that end, our king admits his flight is flawed:

56. Yes, you know you should have arrived in a manner more romantic, befitting your soon-to-be-really-true-this-time status as outcast.

56.1. A romantic in exile, a successful runner-awayer

56.2. from all the stuff that was so bad you couldn’t stay and fix it.

57. It’d suit you – and your story – more if you’d used a mode of transport more exotic.

57.1. A trampsteamer.

57.1.1. Something to weather-beat you.

57.2. Che had his motorcycle trip, where heroes were found, destinies forged, myths made.

57.3. You? You had the Eurostar.

57.3.1. Your heroism stretching as far as trying to sneak champagne from first class.

57.3.2. Stuck in the tunnel for hours ‘due to the inclement conditions at Calais’.

57.3.2.1. The conditions are always inclement at Calais.

57.3.3. One couple got so bored, they started the mile below club.

Of course, in the passage above, it would seem that the mother country being fled is Britain, contrary to the usual refugee narrative of Britain being the desired end destination. It was a country in which ‘you landed … expecting / 148.1. not milk and honey / 148.2. but maybe tea and sympathy. / 148.3. Instead – beer, bronchitis and beatings’. Description of the ‘beatings’ comes later, and after the comedic set-up of the above; the full force of it comes like a punch to the gut. Thenceforth the book takes a hard swerve, detailing racist violence and court proceedings. After the laughs, all we can do is listen meekly, a chastened audience. Dastidar’s power over us is assured.

The use of this legislative enumeration recalls the expropriation of legal register by Layli Long Soldier in Whereas, though Dastidar’s deployment is more colloquial, like a stand-up comedian dispensing kidney shots of political analysis. The force of Saffron Jack is in these whiplash changes from the funny – no work of poetry has ever made this critic laugh more – to the cutting (champagne in the first class bar to the plight of migrants in Calais) combined with a witty evisceration of the very concept of nations as per Benedict Anderson’s admonition that they are ‘imagined communities’. They ‘aren’t lucky collections of soil and flesh, blessed by a smiling God’. Saffron Jack tells us, ‘They’re as much an invention as the wheel, as jelly beans’.

Stephanie Sy-Quia is a freelance writer and critic based in London. Her writing has appeared in Granta, The White Review, Poetry Review, Poetry London, The Times Literary Supplement, and others. She is a member of the Ledbury Poetry Critics Programme.

Buy Saffron Jack by Rishi Dastidar from Nine Arches Press.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.