An interesting poetic constellation in this triad of new pamphlets; each has similarities to the others, but there are marked differences too. Elaine Baker’s Winter with Eva (V. Press) and Astra Papachristodoulou’s Stargazing (Guillemot Press) in particular are poles apart in formal and narrative strategies, and many readers may have a distinct preference for one or the other’s approach, while Clive Birnie’s playful Palimpsest (Verve Poetry Press) draws from its own galaxy of references and allusions. Nevertheless, a reflective consideration of all three may offer some insight into the scope and range of contemporary poetics and emerging voices, and, of course, the small presses that promote them.

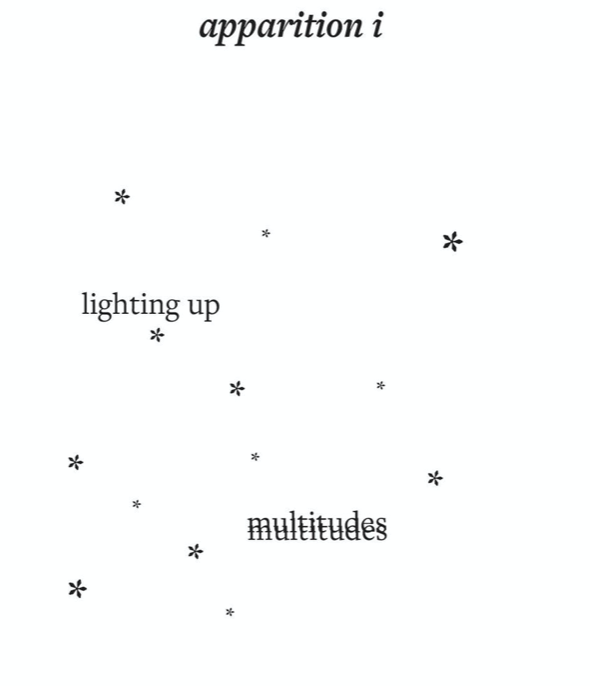

My eyes, and my hands, were first drawn to the gorgeously tactile midnight blue covers of Stargazing: Guillemot Press make particularly fine publications and this one is exceptional. Papachristodoulou’s strategy of a sequence of ‘aperture’ poems is really intriguing and demands the reader adopt a different way of reading the Daedalus and Icarus myth partially retold throughout this text. There are three striking aspects to this approach: the first is that typographical and punctuation marks have, at times, a significant presence. There are star-like asterisks, appropriately, for example in ‘apparition i’:

where a glimmering constellation offsets both the clarity of illumination (‘lighting up’) and the ambiguity of bifurcation (in the blurred ‘multitudes’). Other poems revel in backslashes, evocative of sleeting rain or other sorts of falling. Secondly, there is a consistent use of the 10-line square shape for each poem; it functions as a frame inside which the reader perceives the narrative, and a (literal) window through which the narrator (such as there is) observes the mythical drama. Don Paterson once described the sonnet form as ‘a small square poem.’ Papachristodoulou’s pamphlet, while not a sonnet sequence, quite literally comprises small poetic squares that function as boxes for dreams (to paraphrase Paterson further). Finally, the square framework, when filled to its own borders, sometimes truncates words themselves, so that a reader not only ponders the gaps and resonances offered by poetic language, but what has been severed from within that language: ‘suspended’ includes the lines: ‘the answer is terse & to the poi’ and ‘the carvings they’ve come to lif’; other poems play on the possibility of an end-of-line word fractured rather than truncated (I liked ‘god / lings’ in ‘aphroflights’).’ Here are the final five lines of ‘epitome’:

the poets sleep while the world

timelapses into wingless tomor

rows of matter together in the

past and afterlife webs that

link poiesis and void together

The more one contemplates the lines, the more semantic possibilities emerge, as the eye considers ambiguities within words and phrases, and the white spaces between words play their part too. As well as a flickering mythical narrative, these poems, with their attention to both phrase and white space, word and silence, ‘poiesis and void’, offer reflections on an almost metaphysical level.

Winter with Eva is an altogether different sort of narrative; lucid, coherent, and set in the all too recognisable culture of Brexit Britain and its whipped-up hatred of the other: in this case the Romanian Eva, who is loved by Sean, the speaker of this love story in poems. A foreword acknowledges an obvious debt to McGough’s Summer with Monika and I was reminded of other collections that chart an affair – Duffy’s Rapture, Padel’s Rembrandt Would Have Loved You, Hugo Williams’ Billy’s Rain: it’s a popular format. The difference here is the sharp delineation of thuggish prejudice against immigrants, revealed during casual work conversations (‘Where’s she from?/ Saw that coming. As if I don’t know where this is going’ in ‘Water Cooler’), in crude slogans (‘F*** EU WE STILL BELEAVE’ in ‘Polski’), and finally in outright violence (‘Turning the corner we see it – / windows smashed in, door gaping’ in ‘The gutter’).

There is also (for me, anyway) a disquieting easiness with which the ostensibly loving Sean exoticizes his foreign girlfriend (‘you with your words like exotic birds’ in ‘Scent’). Later, petulant jealousy surfaces when he misinterprets Eva’s friendship with Aleks the Polish shopkeeper (‘I dream there’s broken glass / and I can’t use my feet […] Eva, you’ve done this’ in ‘Glass’). Sean’s flawed character adds an extra level of narrative tension to these poems, something I appreciated. There are many fine images and lucid lines, especially the innovative ‘Whiteout’ (‘Then you push me so I’m knee-deep in ice sugar, / tell me to open, / slip snow in my mouth, a white wafer’). I liked the quirky tenderness in ‘Earbud’ and ‘Creation’; the latter also contains rhythmical, visceral language for making art: ‘You scratch around for dirt and spit into your palm, / work to make the paste to paint a man’. The poem delves into Eva’s backstory, but its energy is in its imagery.

My one caveat with this pamphlet is that some of the poems feel almost too easy to read at a surface level, too prose-like to make full use of the implications and ambiguities that lineated poetry can offer. Poems such as ‘Water cooler’ and ‘Cupboard’ could arguably work just as well as prose passages. Free verse is prone to this criticism and much might depend on what one expects and enjoys from a poem. In places here, I wanted to have the opportunity, as a reader, to tease out echoes and connotations at a greater depth than were offered. But perhaps my perceptions had been skewed by prior immersion in Stargazing? On the level of voice and story, I enjoyed Winter with Eva very much.

Moving to Clive Birnie’s Palimpsest, we have the story of another compelling, eponymous female character, but this female is fragmentary and elusive by nature and name. Birnie introduces his pamphlet as a concoction of cut-up and collage from various serendipitous sources. The result is great fun: Palimpsest enacts her own technique; she is bold and hectic, flirtatious, and a little dangerous. Of course, she is also pure performance, a masquerade, for those who want to read a little feminist psychoanalysis into her construction. There is a trace of romance, though it wears its threads lightly. But like Eva in Baker’s pamphlet, Palimpsest is an artist: on page 13 we find her ‘hacking something in the bathroom, / the floor covered in the spread of half finished jigsaw.’ There is a lot of cutting in this poetry, entirely suitably, and in fact I found many lines that could be an observation of Birnie’s poetic process here just as much as they are part of the surreal storyline. For example, on page 22, Palimpsest muses on her own (imagined) embodiment as a sort of organic storage device:

“Bodies are museums in themselves,” she says,

“organ, fat and bone space where we archive,

store and hoard. This capsule (she taps her chest)

I have inscribed with all the learnings of my mouth.”

I rather liked the transferred truth of Palimpsest’s statement here: we humans are all living capsules inscribed with what we have consumed, literally or metaphorically. Palimpsest herself, though, is a metatextual trickster, intensely self-aware, without really having any self at all. I liked the ironies in Birnie’s subversion of source-texts, and the light-touch control as these untitled poems unfold in their haphazard, but somehow convincing, sequence.

Each containing their own distinct energy, these pamphlets present a vivid array not only of the fine new risk-taking voices on offer today, but the presses that scope and illuminate them. However you like your poetry, then, be prepared for a thought-provoking line-up.

Sarah Law is a tutor for the Open University. Recent publications include the PBS selected My Converted Father (Broken Sleep, 2018) and Therese: Poems (Paraclete Press, 2020). She edits Amethyst Review, a journal of new writing engaging with the sacred.

Elaine Baker’s Winter with Eva (V. Press)

Astra Papachristodoulou’s Stargazing (Guillemot Press)

Clive Birnie’s Palimpsest (Verve Poetry Press)

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.