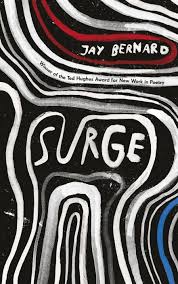

It is noteworthy that the first word of the opening poem in Surge (Chatto), Jay Bernard’s searing debut, is remember. Here is a collection against forgetfulness; a refutation of any presumption that the past is the past at all. Set between the pillars of two disasters, the New Cross Fire of 1981, which claimed the lives of fourteen young black Londoners, and the Grenfell fire of 2017, Surge is a ledger of injustice and resistance, a book of haunting and disquiet.

‘To read the archive’ states writer Saidiya Hartman, ‘is to enter a mortuary’. For Bernard, whose multidisciplinary practice has long invoked historical events, the archival material in Surge serves as a springboard for voicing the unspoken and, more tragically, the unspeakable. Given the devastation of the events surrounding the New Cross Fire, Bernard (pronouns: they/them) is courageous in choosing to draw upon this history. They are also deeply skilful and considerate with its handling. This is apparent, for instance, through their use of the first person perspective across the collection. As the reader, we are met throughout with I, we, my, me, us and our – yet so rarely do these act as a unified lyric voice. Instead, we encounter in these poems a poly-vocal affect, the creation of a multitude of voices emanating from the vastness of black Britain. In ‘Clearing’, the speaker – a victim of the New Cross Fire observing the collection of their remains – opens the poem with ‘He takes my head and places it in a plastic bag’. In ‘+’, the poem that follows, the speaker replies ‘my son isn’t a culprit, and how dare he imply it’ when a police officer racially profiles his missing son, suggesting culpability for the fire – when in fact the son died in the blaze. ‘I came here when I was six’, opens the speaker in ‘Proof’; ‘We have transformed this country’, says another in ‘Duppy’. Appearing largely without italicisation on the page, the voices across Surge converge, creating a collage – at times a chorus – of utterances reflecting the experiences of black people at the hands of the British state.

Central to the reading of the collection are two refusals, one folded neatly inside of the other. If the first refusal is that of declining to perceive the past as behind us, the second is to see those whose lives were lost as gone and unworthy of our attention; as beneath us, literally and figuratively. In Surge, the dead are here and now. They are hungry and eager to be heard. In ‘Duppy’, one of many poems in which this is felt, the speaker cries ‘No-one will tell me what happened to my body’ amidst a protest taking place in the wake of the fire. They follow this with:

I see my picture on a sign my name

as though the march

were my mother’s mantelpiece Lewisham the frame

every face come in like a cousin

tall boys carry my empty coffin

Later in the poem, when the speaker notes ‘The crowd passes through me’, we understand the speaker’s experience of their own disembodiment. We are forced to share their confusion at their invisibility; their separation from the living juxtaposed with their lingering, yet body-less presence. In constructing this, Bernard asks us to consider not solely the loss of life and the devastation of the survivors but also the limbo into which the dead are thrust. It would be neglectful to read this as little more than a quirk that Bernard makes in shaping the collection. By positioning the dead as active speakers who continue to inhabit their community, Bernard frames grief as a spectrum experienced by the victims as well as the survivors. There are no platitudes to be made about the dead being free from suffering whilst loved ones fight for justice in their wake. Bernard remains faithful to the truth of the matter, which is that until today there has been neither justice nor closure, nor an end to suffering for anyone affected by the New Cross Fire – alive or otherwise.

The collection’s later turn toward the Grenfell tragedy provides a through-line from a not-so-distant history to the contemporary. In ‘Sentence’, we again meet the victims of state-sanctioned neglect, this time in the form of missing ‘mothers and sisters’ and ‘brothers and lovers’ whose images are affixed ‘to the underpass wall’ in the shadow of the housing block which is now a tomb. Worse than the infamous 1968 speech by then Conservative MP Enoch Powell had imagined, we now find ourselves in a future where there are ‘Not rivers’ but ‘towers of blood’.

While the Grenfell and New Cross fires are foregrounded across the collection, there is all the while a wealth in how Bernard’s poetry centres queerness. The ghostly figures in the poems – voices who transcend notions of presence as contingent upon the physical body – make it easier to read Surge as continually rejecting binaries, whether these are alive or dead, male or female, and here or there. In ‘Pride’, when we read ‘my body taps me on the heart’ we glimpse that paradoxical sensation of both having and being a corporeal form, of the dance between state and possession being pleasurable. The boundaries between bodies also fades:

a stranger’s hand on my shoulder became a loving mouth

pressing its heat into mine, urgent tongue searching for a place

to pass the root in that way, to go knuckle deep in another

(‘Pride’)

Elsewhere, in ‘Peg’, the ending ‘Now we are boys together. Bend’ likewise evokes an interplay between ideas of power and softness, elements of threat and play. Had no Grenfell fire occurred, it would have been thrilling to read more of these poems in Surge, as they offer sites of escape and resistance in the wake of the poems relating to the fire of 1981. Nonetheless, with the voice of the text continually shape-shifting, blurring into and out of form, moving through and across decades and bodies, there are numerous ways in which queerness resides within the fabric of the collection.

Timely, but in no way ephemeral, Surge is a glowing debut. It speaks to the continuum on which both the New Cross Fire and Grenfell fires exist – an ongoing chain of events marked by moments such as the Macpherson Report, the London Riots of 2011, and the Home Office deportations of Windrush-era elders who arrived in the UK as citizens. It is a mirror held carefully up to our current age, armed with the transgressive fluidities of black queer selfhood. ‘Will anybody speak of this’, asks the voice of the collection’s closing poem, ‘Flowers’. Without any doubt at all, Bernard intends to do so.

Buy Surge by Jay Bernard from the Poetry Book Society website.

If you’d like to review for us or submit your publication for review, please contact Will Barrett on [email protected]

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.