Get Google ready – you’ll need it…

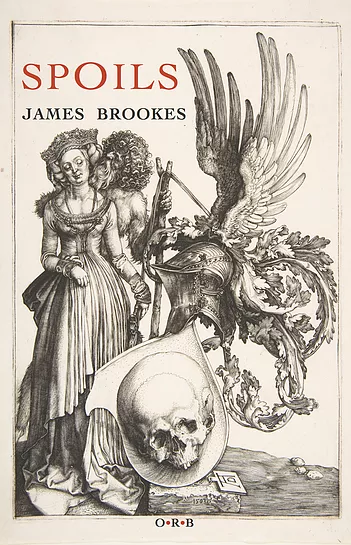

James Brookes has published his second collection of poetry, Spoils (Offord Road Books): a geographical and linguistic excavation of historical and present-day England. These are poems which find their land most fervently on a linguistic plane, in a passionate engagement with the language through which the material reality of that land exists, and comes to the fore of our imaginations. This language, the place, and many of the contemporary questions that the poems raise are reimagined, historicised and made real again with fantastically frank and honest imagery rooted in Brookes’ lyrical and formal diligence.

Brookes exhibits the spoils of his excavation in an accomplished yet playful manner, threading his contemporary wit through formal classicism to manage the register of a complex and engaging work. I said get Google ready because this is an exhibition through the word, and Brookes wants you to work with him as he digs out endangered and archaic diction, to shine the spoils he puts before you. Brookes’ preoccupation with language and phonology is headlined in the opening poem ‘Eschatology, Piscatology’, where the speaker ropes the reader straight into the work, enacting this linguistic attention, with ‘kill’ phonetically assimilating into ‘smile’ as we read.

The halotolerant crocodile

idles in brackish water like a tow truck.

Salt-glands meter in its diapsid skull;

smug fucker that the epochs couln’t kill.

How easily ‘kill’ then closes into ‘smile’,

the lockjaw of a life that rides its luck,

knowing from the hindmost teeth to jackknifed tail

Leviathan is neither fish nor mammal.

Brookes makes his England accessible to the reader; see how the speaker rebalances the scale, which was outweighed with words like ‘Eschatology, Piscatology’, and ‘diapsid’, with ‘smug fucker’. We might almost fear the linguistic accomplishments of this ‘smug’ speaker and the poems as we would the crocodile, until they drop back down to earth with that colloquial encapsulation.

We wade straight into that ‘brackish water’ from the outset, a metaphoric precursor perhaps for the measure of tonal salinity with which the poems to follow are poised. That hybrid balance of fresh-water wit and sour jolting salt-water lexis, which does take some time (and much online digging) to swallow, is tactfully carried through a considered application of metrical skill and flare. Formally, ‘Eschatology, Piscatology’ presents an eight-line poem set in quatrains, with a strict abcc, abcc rhyme scheme, and many of the poems follow relatively strict traditional expectations in this manner. ‘After Christopher Nevinson’s Any Wintry Afternoon in England’ adheres to the conventional fourteen-line sonnet form, structured in couplets with its ‘howitzer’ volta kicking in at the eighth line:

Here it is as lightning, as a man

kicking a football. The ball is now shellburst

of sun void at eclipse. The man’s black boot,

howitzer freeze-framed; legs searchlit elevations,

snapshot in front of smokestack, steam train, slope roofs

rain-scored like fresh scratches on dull metal.

But the formal expectations that accompany the sonnet are dashed with the onset of devices such as irregular and internal rhyme and non-iambic patterning. The collection sets up these expectations, presents its formal capability, only to undercut those same conventions in poems such as this. Brookes utilises both end and internal rhyme here as a means of expanding some of the formal circumscriptions that the poetic tradition, and Brookes’ own choice of poetic scaffolding, establishes. The use of caesura, and internal rhymes like ‘between’ with ‘1916’ persistently disrupt the pace, and pull the reader back over the lines creating a formal overcasting and, by rhyme at least, render the structured borders of the poem more malleable. The end rhyme schemes in this poem also drag lines back to previous end rhymes in a way that seems to hold significance with the content over the formal requirements; the poem is never static. These formal negotiations mark a wider conceptual negotiation between a buzzing impatience for newness and a nostalgic admiration for convention and historical tradition.

This contention is put forward explicitly towards the end of the collection in ‘Tapsel Gate, Jevington’ where the speaker broaches the political and national resonances of the poems head on:

Patriotism? No. I don’t lack the lingo –

no matter what I might offer in my defence

these jangled syllables stay the chains of jingo –

but can I say out loud that my sort spoiled the world

without that sly inflection of self-pity

I cannot shift for money or for love?

The Sussex motto is we wunt be druv

And so the poems assert their own mind and request readings on their own new terms, despite the pasts associated with their historically weighted national content and traditional circumscriptive forms.

This is a testament not only to the skill here, but also the ingenuity. What the work does through these formal applications is bring in to question some of the more explicit propositions it raises regarding nationalism and geographical/ conceptual borderlines. Its formal resistance suggests a more radical outlook on ideas such as cartography both on a physical and conceptual plane.

One charming instance where form and content align takes place across two mirrored poems ‘Fetter Lane Sword’ and ‘Battersea Shield’, which point to one another through staggered line formations, as though pointing themselves out as the central ‘spoils’ of the work.

The playful starkness of the poems is unapologetically set out here and Brookes has a knack for hooking into that good clear image in which the poems are visually anchored. Poems such as ‘Wild Garlic’, ‘Song for a Dark Queen’ and ‘Lines, waiting in the car park while she gets her prescription filled’ where a ‘sycamore raises keloid scars in tarmac’, for instance, all establish those visual fasteners that engage the reader through a delightfully clarified view of the land and a fresh attention to detail. That being said, these are not simply pastoral poems, as ‘Antigeorgic’ (otherwise meaning anti-pastoral in some cases) ironically asserts:

Sussex in excelsis,

……………in midwinter blazon:

deciduous bronze;

……………painted evergreen;

Paradoxically, the poem does paint the pastoral landscape of Sussex. But it proceeds to close with the mythic ‘martlet’ (the legless heraldic swallow on Sussex’s coat of arms) which, in a complex game of linguistic equivalence, pulls the rug from under the ‘county’ who calls the martlet home, by drawing attention to its absolute displacement when ‘failure’ calls the caller from ‘home’, elsewhere:

Rejoice then, my martlet,

……………Your county calls you home.

Rejoice then, my county,

……………Your failure calls you home.

This renders the previous pastoral lines of the poem legless – like the martlet! And that question of place and its fixity is raised once more, in a mind-boggling contortion act between theme and purpose.

Despite their playfulness (which elevates the thoughtful underlay of the work) the poems deal with serious matters. Aside from politics and history, there are real love poems here; in ‘Tenulla’ the speaker watches the ‘Water girl’:

…so blithe against the cold

you swim until the blue tinge of your skin

shames the water:

and in ‘Come Round at Last’, something beyond the pastoral histories that this book uncovers is unearthed:

I went to my histories and found

You entirely without precedent there

…

Little one,

eclogue of strange nucleotides, you’re here –

that lovely catlick of gold is only your hair

The complexity of Brookes’ poems, the linguistic difficulty and intricate rhyme scheme, though treacherous to navigate and labour intensive at times, marks the lexical filigree of his craft, offset by superbly frank, down-to-earth humour, and those vital singular images which cut across the difficultly, bringing into balance a superbly rich and rewarding set of finds.

You can buy Spoils from Offord Road Books here.

You can buy Spoils from Offord Road Books here.

Maryam Hessavi is a British, Manchester-based poet of English and Iranian descent. Her poetry has featured in the Peter Barlow’s Cigarette series in Manchester and is forthcoming in Smoke magazine. She is working on various collections of poetry for publication at present, alongside forthcoming review commissions for The Manchester Review, Poetry London and others.

The Ledbury Emerging Critics Programme was founded this year by Sandeep Parmar and Sarah Howe to encourage diversity in poetry reviewing culture and support emerging critical voices. Open to budding BAME poetry critics resident in the UK, the scheme offers an intensive eight-month mentorship programme, including workshops, one-to-one mentorship and critical feedback.

The Poetry School will be publishing reviews by all eight participants in the Ledbury Emerging Critics Programme.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.