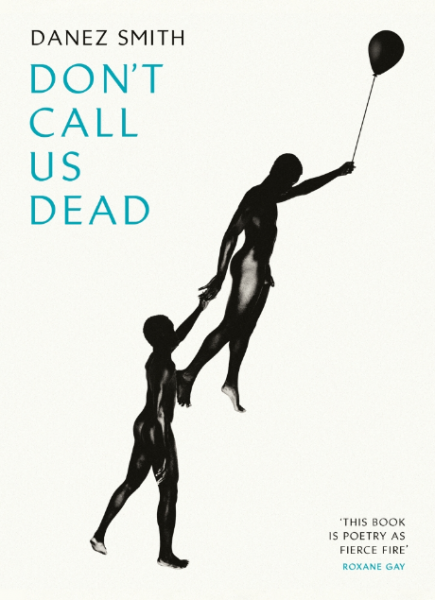

Danez Smith’s Don’t Call Us Dead (Chatto & Windus) interrogates the present, exhumes histories and dares to imagine a future poised in anger, grace and freedom. It is unapologetic in its scope and tender in its pain.

The politics is searing and the language hauntingly beautiful; Smith’s is a craft of lacerating precision. This collection is an elegy for race in America and a fever dream from the throes of desire, illness, violence and becoming. Its locus is a body held in perilous suspension over a vortex of private longings and public un-belongings, its flightpath traced by profound vision and impeccable, bristling labour. This is an urgent work that bears witness to an unimaginable truth.

Smith writes about the America that exists in the creases, gaps and margins of the grand narrative of the land of the free. They pursue the bodies that signal and suffer the burden of otherness – incarcerated for their colour, maligned for their queerness, destroyed for their difference. The poetry operates in sweeps of emotion and the exhilarating possibilities of language, intertwining grief and hope, resistance and eroticism. Smith is a spoken word artist and they lay bare every contour of performance in this work – linguistic, gendered, racialised and cinematic. In their unpeeling of the mythologies of America is a scrutiny of every cell, syllable and speck of stardust that composes the horizon of dissidence in its spectre of brutality and the always already broken promise of salvation.

The collection opens with the outstanding long poem ‘summer, somewhere’ that imagines a new world where time is reversed, dilated and held still, and young black men who have been murdered by the police are ‘unfuneraled’, becoming alive and possible again. In a pitch-perfect poetic feat, Smith imagines in an endless summer a heterotopic space that accommodates and liberates bodies refused by this America. The idyllic opening gives way to the long exposure of a brutal cinematography of death, and the boys are free again but the poet implores: “please, don’t call / us dead, call us alive someplace else”. If black men’s lives were shaped by the interpellation of those who killed them and those who mourn them, by the course of a bullet or the truncated trajectories of history, Smith’s poem marks a point of resistance. That language, like the death, cannot persist in this space. Here, time is suspended in a still shot of jubilance not terror, and this structure of suspension informs the rest of the poem.

somewhere, a sun. below, boys brown

as rye play the dozens & ball, jump

in the air & stay there. boys become new

moon, gum-dark on all sides, beg bruise

-blue water to fly, at least tide, at least

spit back a father or two. i won’t get started.

history is what it is. it knows what it did.

bad dog. bad blood. bad day to be a boy

color of a July well spent. but here, not earth

not heaven, we can’t recall our white shirts

turned ruby gowns. here, there’s no language

for officer or law, no color to call white.

In many ways, this poem is the centre from which the rich, interlocked anxieties of the collection radiate outward. When Smith describes the rituals of becoming a boy again in this world, they are also deconstructing the performances of otherness – of what it means to be black, gay, HIV positive – that scar the poems and the social orders that shape them. Death functions as another baptism as the new names and new bodies reverse the gyres of violence, of colonial crossings, the persistence of enslavement and incarceration, police brutality, the prison industrial complex. This is a time before and after America – a desultory, de-centring poetics of forbidden loving and interrupted being. The image of the boys becoming new moons is a proleptic reaching out to the poet’s desire to find a new planet from which to rewrite an affirmative history of race in ‘dear white america’, a poem that abandons the politics of respectability for a galactic insurrection.

i’ve left Earth to find a place where my kin can be safe, where black people ain’t but people the same color as the good, wet earth, until that means something, until then i bid you well, i bid you war, i bid you our lives to gamble with no more.

The crushing proximity of existential threat is negotiated through both the cellular encroachment of disease and the interstellar expansion to a utopian future. Colonial invasions are turned inside out, neo-imperialism undone, and bodies are reimagined as star, clay and forest in this dark, bright re-inscription of the universe.

Smith articulates the vulnerable body within a cluster of botanical tropes where trenchant politics meets exquisite lyricism. The summer boys are like trees, they pulse with the sap and lifeblood of a new sustenance and perpetual regeneration, their flesh green and vital. In becoming a forest, they both carry the seed and transcend the historical trauma of the strange fruit of blood-riddled Southern trees. The poplar bears witness as Smith’s poetry erupts in a ferocious longing of a dissident pastoral free from black pain. In another section, black bodies become sprouting corpses as funerary and fertility rites speak over each other. It is an almost maternal lamentation from the edge and shadow of the page, and grief is a yearning for a storm of dandelions to unravel time and form a carapace over a broken body that still had a life to live and that can never be mourned fully.

dear sprinkler dancer, i can’t tell if I’m crying

or i’m the sky, but praise your sweet rot

unstitching under soil, praise dandelions

draining water from your greening, precious flesh.

i’ll plant a garden on top

where your heart stopped.

One of Smith’s great triumphs in the collection is their perceptive exploration of different forms of public and private discourse. In ‘dinosaurs in the hood’, they unpack the images of black people that are permitted in popular culture – the hollow stereotypes, the contortions of white auteurs’ understanding of the black body as mere metaphor, and the gratuitous use of racial trauma. Instead, in Smith’s film, the black boy is the subject not the spectacle, the celluloid is a surface for his dreams, it is another pocket of heterotopia where he can slip out of the reach of pain and death, infinite even in its provisionality.

no bullet holes in the heroes. & no one kills the black boy. & no one kills

the black boy. & no one kills the black boy. besides, the only reason

i want to make this is for the first scene anyway: little black boy

on the bus with his toy dinosaur, his eyes wide & endless

his dreams possible, pulsing, & right there.

Variations of ‘boy’ and ‘boi’ pepper the text in a complex web of associations. Subversive in its multiplicity, the word is used to invoke seething eroticism, the history of diminution and infantilisation of people of colour as a continuation of racialised acts of power, and perhaps, most potently, to signify the denial of the innocence and childhood of black boys. For when black boys get killed on the streets and on screen, their victimisation is explained away because of the perception of threat they allegedly pose to white America; they are not boys but thugs; they are rendered simultaneously invisible and abject, irrelevant and monstrous. Smith’s vocabulary springs from the bedrock of the playschool-to-prison pipeline, the impunity of brutalising Tamir Rice or Michael Brown or Trayvon Martin, and from the crisis of mental health that swallows young people of colour whole as America stands by.

When the lyric ‘I’ is invoked, it can only exist as a function of another kind of death – even more anonymised in the utter invisibility of “my barely body telling me to go / toward myself”. To be black and HIV positive is a subjectivity of contrasts, at once hyper-visible and larger than life when one is ceaselessly under threat while perceived as being threatening under a regime of state violence, as well as fading into nothingness as one’s body turns against oneself. Smith’s poetics of composite vulnerability imagines this blackness as white noise meeting silence.

For Smith, the body is evidence of what remains as well as the presage of what can be. In the typographically indulgent ‘litany with blood all over’, the spread of the page becomes the intracellular space of intermingling fluids as ‘his blood’ and ‘my blood’ run into each other, repeated in a flurry of speaking over and crossing out such that the narrative of the hyphenated ‘bloodwedding’ and ‘bloodfuneral’ from the preceding page appears to disintegrate into pixels of illegible bodywork. This is a necessary incomprehensibility, outside the reach of sexual normativity, discursive capture and political categorisation. In the unreadable embrace and clash of coming together in a forbidden intimacy and separated in a predestined early death, Smith evokes the aching loss of irrecoverable love.

my veins—rivers of my drowned children

my blood thick with blue daughters

my blood

my blood

his blood my blood his blood

The intermixing of blood is anticipated in the intertwining of names in ‘bare’, in a testament of love that disavows for a sustained moment the knowledge of a desire forbidden and punished. It is a call for an utter and profound vulnerability to one’s lover, like light being absorbed into darkness, which stands in poignant contradiction to the inescapable and terrifying openness of the racialised, queer, abject body to bullets, needles and discarded obituaries.

if love is a hole wide enough

to be God’s mouth, let me plunge

into that holy dark & forget

the color of light. love, stay

in me until our bodies forget

what divides us, until your hands

are my hands & your blood

is my blood & your name

is my name & his & his

One of the most quietly powerful poems in the collection is ‘at the down-low house party’, a beautifully stratified exploration of intimacy in body and language within a sexual economy that demands normative performance of masculinity.

his sharp hips pierce our desire, make our mouths water

& water & we call him faggot meaning bravery

faggot meaning often dream

of you, flesh damp & confused for mine

faggot meaning Hail the queen! Hail the queen!

faggot meaning i been waited ages to dance with you.

In this outstanding account of speech acts permitted and transgressed, of sexual norms exhibited and disavowed, Smith ‘unfunerals’ a queer interiority from the artifice of a public discourse shaped by homophobia and a fear of difference. There is an incandescent inner life that menaces just beneath the surface and occasionally ruptures with a giddying force. The consequences are visceral and unfathomable, they wed banality to ineffability in a lifetime to be spent too quickly before it is withdrawn, a half-life of desire.

…………a boy with three piercings & muddy eyes smiles & disappears into the strobes

the light spits him out near my ear against my slow & practiced grind

…………he could be my honey knight, the hand to break me apart like dry bread

there is a dream where are horses that neither one of us has

…………for five songs my body years of dust fields, his body rain

in my ear he offers me his bed promise live stock meat salt lust brief marriage

…………i tell him the thing i must tell him, of the boy & the blood & the magic trick

me too his strange dowry vein, brother-wife partner in death juke

…………what a strange gift to need, the good news that the boy you like is dying too

In Don’t Call Us Dead, Smith proposes a prismatic, embodied contemplation of time and space as iterations of otherness. Ferocious, intelligent and epochal, this collection taps into the conscience and consciousness of contemporary society. The text is a palimpsest of desire and difference, of language and history, and in its requiem for black bodies, it signs an urgent disavowal of the state of love and death in America. Smith has produced a revelation and a reckoning.

You can find out more about Don’t Call Us Dead from Penguin.

You can find out more about Don’t Call Us Dead from Penguin.

Srishti Krishnamoorthy-Cavell is a final year PhD student in English at the University of Cambridge. She is part of the Ledbury Emerging Poetry Critics programme, and her essays on poetics and poetry reviews have been published (or are forthcoming) in, amongst others, Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry, Intercapillary Space, Poetry London and The Poetry Review. Her research interests include contemporary poetry, gender and sexuality, ecopoetics, Modernism, literary theory, boarding school narratives and the cultural history of particulate matter.

The Ledbury Emerging Critics Programme was founded this year by Sandeep Parmar and Sarah Howe to encourage diversity in poetry reviewing culture and support emerging critical voices. Open to budding BAME poetry critics resident in the UK, the scheme offers an intensive eight-month mentorship programme, including workshops, one-to-one mentorship and critical feedback.

The Poetry School will be publishing reviews by all eight participants in the Ledbury Emerging Critics Programme.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.