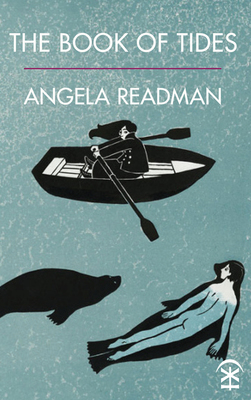

The Book of Tides is a triumph of femininity, transformation and transience. Daring and unsettling, Readman’s poems subvert the status quo, blurring the boundaries between myth and reality with a visceral feel that draws you in from the very beginning.

These are poems that beg to be read out loud, crammed with short, sharp words and a smattering of local dialect which produces a natural chanting rhythm. The collection centres on the inhabitants of a small fishing community on the North Sea coast, but there is also a layer of mystery here, and many of the poems have an otherworldly, elusive quality, taking their inspiration from folklore and superstition. I felt confronted, reading the title poem, as I met with this image of the mother figure standing firm on a cliff top:

Like that, the old lass could switch into a ship’s mast,

stood on that cliff, air wringing a swell of hips

out of her skirt. Then, she was Ma again,

dragging me through the plothery snicket,

back to the cottage. Outside tinkled and strode.

Fishermen knocked, bags of whelks at the door,

trout like rainbows dandled in raw hands.

Aye,

the woman had a knack for the wind, knew it,

whisper to gale.

This woman is typical of the characters within this book, exuding an incredible strength, almost divine, yet rooted, at the same time, in her everyday surroundings.

Readman often creates unnerving feminist alternatives to ancient myths. Her prose poem ‘Featherweight’ echoes the story of Leda and the Swan. This time, however, the woman has the strength and control, and the process of falling in love transforms her body:

The skin felt too big, hand-me-down feathers too heavy for flight. Then, it fit like a blizzard, down between my legs tickled my petticoats to shreds, swept my skinny legs up. It was the same for her, I suppose – all this flying and loving and not knowing how to stop. The steel of our wings can break first love’s back – we do not know our span. Boys who got too close snapped, spines skinny rushes whistling in the wind.

This female/bird metaphor runs throughout the collection, alongside the symbolism of water as metamorphic, fluid and feminine. In ‘The Morning of La Llorona’, Readman turns this Spanish legend of the weeping woman into a story of transformation. Though it begins with grief, there is a growing sense of freedom, which leads to a release of love:

After the drowning, I lay my palms on the table

and watched my fingers soak into dead wood,

I saw the grain lighten, my old hands draining away.

I untied my apron like a raft the colour of fire.

It couldn’t save us. Cotton roses drifted, moved

to bits by my hips, the white water of my neck.

I was a woman of water, foremost.

Whilst the majority of poems in the collection are set within the remoteness of the fishing community, others exist unmistakably in a present day we might ourselves recognise. Subversion and mystery flow through these poems too. ‘What the Sindy House Taught Me’ is full of humour, but there is an edginess here as well. The poem takes child’s play literally, illustrating, in deceptively simple language, the vulnerability of being female:

someone who looks

like you used to will sit on your patio as you lie

outside naked. She is waiting for a man

to knock on her cardboard door. Carefully,

watch him not fit in the lift, float up, and in.

This is why her house has only three walls.

Men are conspicuously absent. Instead, the focus is very much on the female experience, with an emphasis on the mother/daughter relationship. The poems have a strong feminist slant, but they also embrace women in the domestic sphere: as wives, lovers and mothers. We see a wife expressing love for her husband in ‘The Woman Who Could Not Say Love’:

If there’s a more fluent way to write it

than with steel, a needle held

to the window, looping an apostrophe

of sunlight to his coat,

she doesn’t know it. Let a stitch

in a frayed pocket proclaim

what thinking of him is.

There are exceptions to this rule. The disconcerting poem ‘My Father Snaps off Mermaids like Porn’ is full of sexual and menstrual imagery, and could be read in a number of ways. There is an emphasis on puberty, and the mystery of separation between father and daughter, as the father is left behind in his shed, while the daughter begins her transformation into something reminiscent of a mermaid. Yet there’s also a strong feeling of connection between the two:

I stare at the blood on my legs, a join-the-dots of my life.

Because it’s not for us, Son, this merman stuff, sackless

drifters, our junk in a glittery purse. I open the door.

My father follows, cuts a finger on the knob and holds

up a scale like filed rain. We will find them all year.

Other poems are more firmly grounded in the real world, particularly those which focus on the loss of parents. In ‘The House that Wanted to be a Boat’ we see the helplessness of grief contained within a metaphor, as we watch a house slide irrevocably into the sea:

Mother’s face is a gable,

wallpaper still hanging on, plaster ducks

on the wall pointing out all this space

on our backs. There is nothing to do

but stare as the roof tips its hat.

Bricks buckle up, and freefall.

The collection ends with the moment when ‘The Book of Tides Closes’, a kind of haunting elegy to past love and youth. It is also a reflection of the book as a whole, as tides and times ebb and flow, women grow older, and the men might, at last, have their say:

The magic is gone,

my bones no longer inkle for storms.

And still I stare out at lead wings, a scrat

of gulls on the outhouse, beaks blotted

in crescents red as kisses that won’t wash.

I listen to bird squall like drowned men

rearranging old squabbles all day, as if one may

finally find the right words, get the last one in.

This is a collection which transforms in more ways than one, twisting our perceptions and presenting new takes on everything, from bees and swans to folklore and femininity. These are poems that shift and shimmer as you read, telling their tales with strength, yet questioning and interrogating their own world – a world that is at once both magical and physical.

Reviews are an initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at – [email protected].

You can

You can

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.