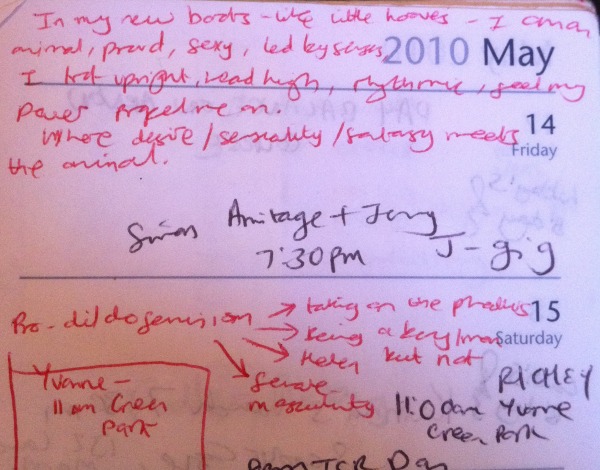

Like many of the poems in Black Country, it took a long time for ‘Sow’ to travel from its first notes to its final form. It began as a scribbled note in my diary in May 2010. I was walking along Highgate Tube platform in a new pair of black boots and, hearing them trip-trapping, I looked down and imagined them as little hooves and myself as some kind of animal. On the tube I made this note in my diary…

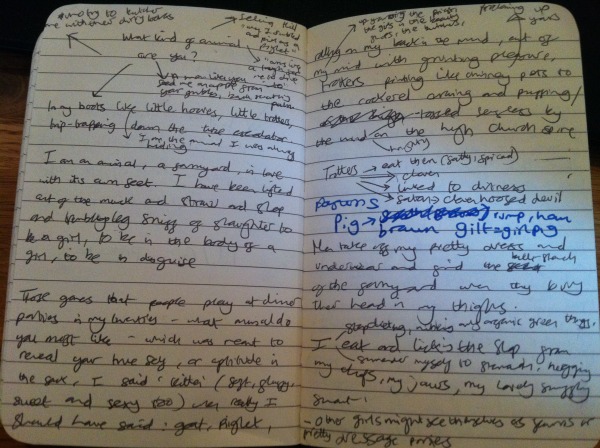

A few weeks later I did some free writing on the idea. This is something I almost always do when I’m starting a new poem, read and write freely around it to help myself discover connections, images and language without feeling inhibited by worries about structure, form or ‘poem-ness’.

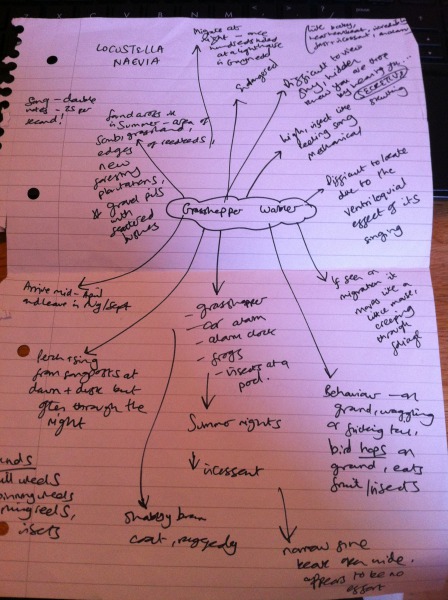

Sometimes I even make big sprawling spider diagrams like this one from the poem ‘Grasshopper Warbler’…

I find this looser, wilder approach can lead me into more surprising or exciting places. Looking at the first notes for ‘Sow’ (if it’s possible to read my appalling speed writing) you can see that many of the lines from the final poem are here in their fledging form. My handwriting in my notebooks is always incredibly messy, very different from my neat primary school teacher everyday writing, and I suppose this reflects the excitement and urgency I feel when I’m making those first drafts.

These notes stayed in my notebook for a little while until there was a spark that lit the tinder. I was in the changing rooms at the swimming baths and I overheard a girl, who thought she was alone, stepping on to the scales and hissing at herself in a pained awful voice: “You fat pig”. My heart hurt for her and all evening I couldn’t get her words out of my head. I wanted to write a poem that could transform that moment and those words into something rebellious, defiant, unashamed; to take that idea of female animality and make it a source of pride and subversive sensuality.

I got to work on the notes and began making drafts in my usual messy enthusiastic rush – lots of stop/starts, false turns, writing and crossing out and writing again. Then I began to type up. I always save each draft on my computer so I can go back if I need to. Sometimes you find that you tinker so much that you lose the soul of the poem and need to go back to find it again. Interestingly, ‘Sow’ didn’t start in full dialect and perhaps this was what was holding it back. I couldn’t get the voice quite right. It didn’t seem to express the boldness or the rage that bubbled in my head and my notes.

Here’s what the first verse looked like before the dialect. At this point the poem was called variously (in its many drafts!) ‘New Boots’, ‘Pig’, ‘The Animal I Am’.

Trottering down the street in my little hooves

I am all animal, farmyardy sweet, fresh from the filth

of straw and swill, the tembly-leg sniff

of the slaughter wagon. A guzzler, gilt, trolloping

and podgy in my new cloven boots. Root your nose

beneath my dress and gulp the brute stench of the sty.

Feeling that it wasn’t quite working, I let the poem whirr round in my head for a few days. A week or so later I tried again, this time using some Black Country dialect, something new I was trying in my work. The key was in the lock: the poem opened up to me.

I made a draft I was happy with and took it to my workshop group. I find that the advice of a supportive, honest workshop can work wonders for a poem – good readers can help you to see how and why things might not be working and suggest ways to push the poem forwards. I might not always follow all the advice given but I’ll certainly think it over before making my own judgements. So: More anger, more drive, tell us more about the brutality of chauvinistic world she’s rebelling against, was their advice. They loved the trotters-up to the prissy cockerel at the end and wanted more of a build up to that moment. So I went back to the poem and drafted again.

This time the voice became more concentrated, a more fully realised character, further away from myself. The idea of the speaker resisting being controlled and fettered by brutality emerged more clearly with the new lines about the ‘dirty fists’ and ‘them nights, me eyes rolling white in the dark’. As I worked and rewrote, the little sow began to come kicking to life.

Sow

Dainty footwear turns a young lady into an altogether more beautiful creature…

– Eliza Sell, Etiquette for Ladies¹

Trottering down the oss road² in me new hooves³

I’m farmyardy sweet, fresh from the filth

of straw an swill, the trembly-leg sniff

of the slaughter wagon. A guzzler, gilt.

Trollopy an’ canting. Root yer tongue beneath4

me frock an’ gulp the brute stench of the sty.

I’ve stopped denying meself: nibbling

grateful as a pet on baby-leaves, afeared

of the glutton of belly an’ rump5. I’ve sunk

an’ when lads howd out opples on soft city palms

I guttle an’ spit, for I need a mon

wi’ a body like a trough of tumbly slop

to bury me snout in6.

All them saft years of hiding at ‘ome

then prancing like a pony for some sod to bridle

an’ shove down the pit, shying away

from ‘is dirty fists. All them nights,

me eyes rolling white in the dark when the sow I am

waz squailin an’ biting to gerrout7.

Now no mon dare scupper me,

nor fancy-arse bints, fer I’ve kicked the fence

an’ I’m riling on me back in the muck,

out of me mind wi’ grunting pleasure,

trotters pointing to the heavens like chimdey pots,

sticking V to the cockerel8

prissy an’ crowing on ‘is high church spire.

Black Country glossary:

oss road – street ; gilt – sow; canting – cheeky or saucy; guttle – chew;

mon – man; saft – foolish; squailin – squealing or crying

(‘Sow’ received second place in the Poetry London Competition in Summer 2011)

1 – I loved the cheekiness of this epigraph, the dainty footwear being the little hooves and, of course, the transformation being that of girl into sow, truly an altogether more beautiful creature!

2 – ‘Trottering down the oss road’ – A perfect Back Country phrase for this animal poem!

3 – ‘in me new hooves’ – The little boots from my original inspiration and notes.

4 – ‘Root yer tongue beneath’ – I chose this line ending as it seemed to make the lovely vulgarity of the following line even more of a surprise.

5 – ‘the glutton of belly an’ rump’ – Here is the inspiration that I took from the girl at the swimming baths. I wanted those feelings of shame and self-denial to be renounced by the little sow.

6 – ‘bury me snout in’ – Inspired by the final amazing lines in one of my favourite love poems, Selima Hill’s ‘Please can I have a man’.

7 – ‘squailin an’ biting to gerrout’ – This verse was one of the last things to fall into place in the poem and only came after the poem was workshopped.

8 – ‘sticking V to the cockerel’ – Again, an image from my first notes.

Wonderful

Really enjoyed the process to the end product