When writing is hard and the poems are turning stony-faced and slow, I tell myself there are so many things harder and slower to hold onto than a poem: first, a breath, and second, a stone. I take one good, deep breath and let it go. Then I take one good, deep lump of time and it takes hold of me.

A stone of any size will do but if you can balance it in your hand or on your knee, all the better. At any one time, somewhere about my desk or person, I’ll have a pebble or a fossil that I’ve just picked up from a car park or a beach or a field. A flint from Wiltshire, cool as a slice of milk. A pocketful of olivine-rich gabbro from Devon, cracked yellow like a clutch of cold green eggs. A gnarly old oyster direct from the Triassic which goes by the name of ‘devil’s toenail’.

These all sound like the beginnings of a pretty dreadful breakfast but they might once have been part of a forest or an ocean or they might be a perfect cast of the shape of a burrow, an ancient animal going about their life, formed with the dissolved body of that same ancient animal going about their death.

As pretty as they are dreadful, these little portable landscapes are a champion breakfast for poets. I like to start each day and each poem with one.

When the writing is particularly hard, I start drawing. Sometimes it’s good to let the hands move differently. Sometimes it’s good to just keep them moving. Every time, though, there’s something important and unexpected that moves between the drawing and the writing.

Last year, I had an exciting invitation to devise a workshop for the Bodmin Moor Poetry Festival with the archaeologist and illustrator Rose Ferraby. I first encountered Rose’s work in Melanie Challenger’s sequence of poems The Tender Map (Guillemot Press, 2016) and Rose’s churning, slippery wax and watercolour illustrations went on to win the Michael Marks Award for Illustration in 2017. Rose and I arrived in Cornwall with rucksacks jangling full of fossilised coral, Neolithic hammerstones and one gaudy little geode and had the happiest of mornings working with the intrepid poets at Bodmin Moor. After taking our time choosing which rocks we wanted to work with — weighing them carefully in each hand, holding them up to the light, giving them a proper, solemn sniff — we began the day by taking it in turns to reassure each other we couldn’t draw. We were poets, poets who couldn’t draw, we all told Rose who carefully and generously showed us we could.

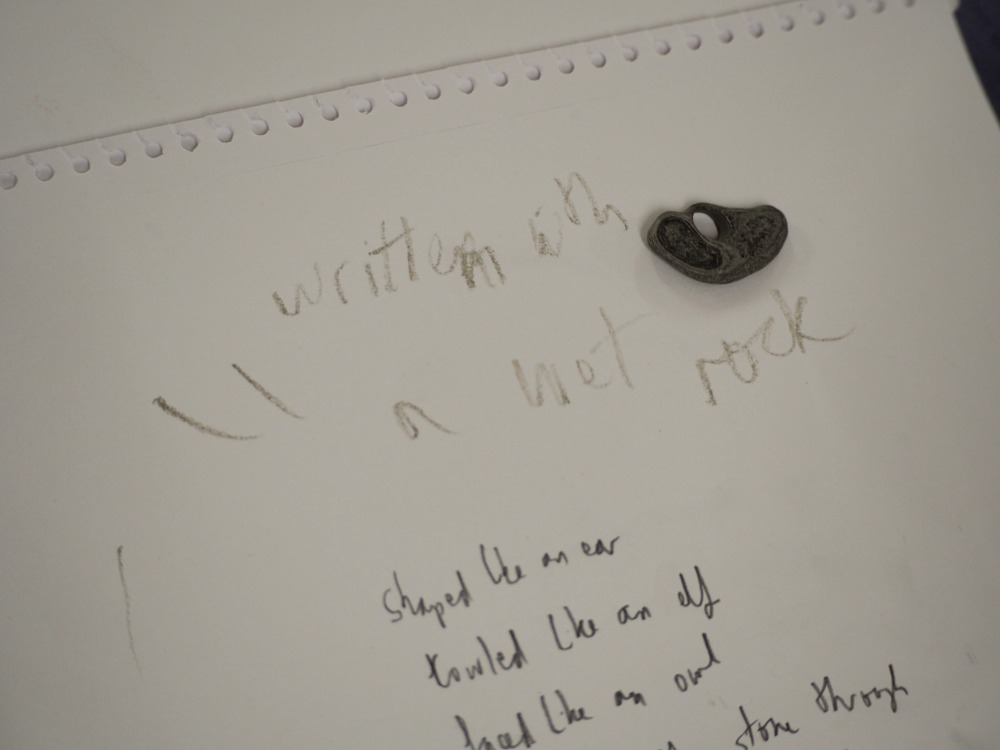

Alternating between writing and drawing exercises, we set off to explore the tiny terrains of our chosen rocks with graphite, Conté, wax and watercolour, imaginatively expanding them into vast, strange worlds to inhabit in our writing. Eventually and literally, we were drawing with our eyes closed, sketching by touch and texture. It was a moving and meditative morning and we even had a little lie down, measuring the breath in our poems by balancing the small weight of a pebble on our stomachs. At one brilliant moment, a poet dipped their small slate hagstone into a glass of water and began writing with the wet rock straight onto the paper.

By the end of the morning, we weren’t sure what was poem, what was illustration and what was – best of all – both. Since that bright morning in Bodmin, I’ve been using the techniques Rose taught me (that’s my smudge of flint and Triassic toenails at the top of the page) and this, in turn, has taught me more about how a poem happens in the space between one thing and another.

This October, Rose and I will be bringing our rucksacks of rocks to London for a whole day of poetry, illustration and geology. Whether you want to work with poetry, illustration or somewhere in the rich seam between, we invite you to spend some deep time with us and join our expedition across the surface of a stone.

Expand your poetics, develop new artistic skills, and delve into ancient geologic time with Holly Corfield Carr and Rose Ferraby in their upcoming Saturday workshop, Geologic Encounters. Call 0207 582 1679 or book online.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.