In the first of a regular series of feature-length interviews with independent publishers, we met over a few rounds with Emma Wright in our imaginary poetry theatre pub somewhere in Lambeth, asked her about the early days of The Emma Press and why she believes it’s never been a more exciting time to be going solo.

Hi Emma. What are you drinking?

Emma: A margarita!

How long has The Emma Press been running?

Emma: I started developing the idea of The Emma Press in 2012 and published the first book in January 2013: an illustrated book of love poems called The Flower and the Plough, by Rachel Piercey. Initially I wanted to run a gift business called The Emmporium with a sideline in poetry books, but then I realised I couldn’t sew enough silk brooches to make a living and also I really enjoyed the whole process of publishing The Flower and the Plough. So I shifted the emphasis and ditched The Emmporium as a name, but kept the idea that The Emma Press could produce gifts as well as books.

What were some of the practical things you did to get started?

Emma: By 2012 I’d been single and living at home with my parents for a year while still working at Orion Publishing Group in London, so I’d managed to save about £6000. After I quit Orion, I bought an iMac, a good scanner, some sketchpads, some drawing nibs and ink, and a lot of silk (see above).

I had two months remaining on my non-refundable annual rail pass, so I used it to come up to London several times a week to meet people in the industry and chat about my plans. I met up with digital publishing experts, a publishing lawyer, the founder of a women’s magazine, and some artists. I asked them how they came to be in their current positions and whether they thought it was a terrible idea to try and set up a poetry publishing business, and luckily everyone was very encouraging.

In September 2012 I started the Prince’s Trust Explore Enterprise scheme, just because a friend mentioned in passing that the Prince’s Trust might be helpful to me. I used my £200 ‘Will It Work?’ grant to pay for my stall fee and some fliers for a local craft fair in May 2013.

Does your personal background lend itself being an independent publisher?

Emma: I wasn’t a particularly good student, but I do think that the work habits I got into when I was studying for my Classics degree have really come in handy now. I got used to doing stupid amounts of work in short spaces of time and balancing late nights with intensely productive days, and I’m not too daunted about learning new skills very quickly.

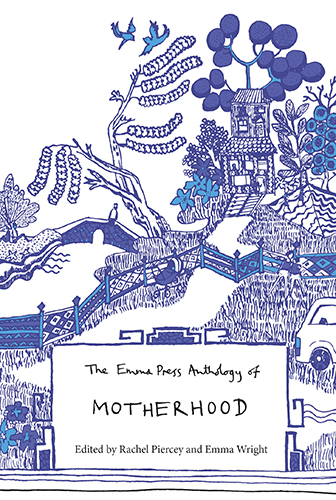

Just after Christmas, my co-editor Rachel Piercey and I turned around The Emma Press Anthology of Motherhood in 6 weeks: we did everything from reading over 1000 poems to making the final selection, replying to all the submissions, editing the poems, illustrating them, liaising with the poets, designing the cover art, writing the introduction, getting quotes and samples from 5 printers, organising the launch party and 10 additional events, and launching the next call for submissions.

Where does the name The Emma Press come from?

Emma: While working on Orion’s backlist, I realised that several well-known publishing imprints are men’s names: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, Allen Lane, Gollancz, Faber. I also realised that no-one outside of the publishing industry really knows or cares about any of these men or about any of the publishers. People have a vague sense of loyalty towards Penguin, and Faber is respected, but apart from that I think that publishers have very poor visibility amongst the general public. I wanted my publisher to be deeply personal to me and I wanted the name to reflect that. I don’t think corporate blank professionalism is doing publishers any favours.

Could you describe the sort of poetry you publish?

Emma: I publish poems which move me and leave me buzzing when I reach the end. I want to publish books which make people happy, which doesn’t mean I publish fluff and bubblegum or avoid difficult issues. I publish poems which emphasise our common humanity and which make me pleased that this poet exists, and I hope that other people will also feel this connection to another human being. I like rhythm and rhyme and an awareness of form, and I also like bold ideas expressed through playful language.

I was pleased when we published a pair of pamphlets in March which were so completely different, because I hoped that this would make it very clear how Rachel and I are open to all different kinds of styles. We published several books of love-themed books to begin with, and I think there will always be a place for love poetry at The Emma Press, but we’re moving more into activism now, with our game-changing Anthology of Motherhood and Fatherhood and our imminent call for poems about the UK political landscape.

How are you different from other independent publishers?

Emma: I think a lot of small independent publishers are trying to be like the big guys, with their cover design, the writing style of their authors and their marketing techniques. Having worked for one of the biggest guys, I really don’t think this is necessary or particularly helpful, as the major publishing houses are all in need of a shake-up. I mostly try to approach my method of publishing with an open mind, drawing on what I feel as a consumer.

My book covers look deliberately handmade, and I promote my books through my calls for submissions, The Emma Press Club, where people have to buy a book from my website in order to submit, and my newest idea, Poem Club – like a book club but for a single poem from one of my books each week. I have a feeling that a lot of the poetry I publish is different to the mainstream too.

On average, how many books do you sell in a year?

Emma: I’ve only really started making proper sales since Christmas, but so far it’s been 150 a month on average.

Do you sell more online or by wholesale/retail?

Emma: I sell mostly online through my website. Sales through my distributor have been picking up nicely over the last few months, but since I don’t receive the money until 6 months after the sales are made, I’ve been focusing on building up my own customer base for now.

What have been some of your biggest successes so far?

Emma: The Emma Press Anthology of Mildly Erotic Verse got a lot of attention when it published last September, and it’s continued to sell steadily from my website. The Emma Press Anthology of Motherhood was also a big hit for us, as it tapped into some feelings which don’t tend to be discussed in the mainstream media.

But the biggest success is still our first book, the single-author pamphlet The Flower and the Plough, by Rachel Piercey. We sold a good number when it was first released and it’s continued to sell itself quite steadily. When I ran a pop-up poetry shop on Lower Marsh Market last summer, I could watch people reach for the little pink book, read a couple of lines and be instantly sold. Rachel’s a brilliant poet and I’m really happy with my design for the book, so I think the combination of these factors has made The Flower and the Plough a little dynamo.

What’s the best thing you’ve found from the unsolicited pile?

Emma: We don’t have an unsolicited pile: we work entirely with calls for submissions, for themed anthologies and various kinds of pamphlets. I could in theory invite pamphlet submissions all year round, but I find that the only way I’m able to cope with the volume is to have a set period of welcoming submissions and a set period for reading them.

How important is the physical book design for you?

Emma: Very! I do everything I can to make the reader’s experience enjoyable while at the same time representing the poets in their best possible light. I also want the reader to be aware of the amount of care and human effort which has gone into creating each book, so I choose paper which is a good colour, weight and smells nice (usually Popset, which is partly recycled and smells a bit like icing sugar), and I design covers which are attention-grabbing and reflect the spirit of the poems within. I think text-only covers are a bit of a cop-out: laziness masquerading as classy restraint. There’s only a handful of poets who have enough recognition among the general public to sell books by their names alone.

I illustrate most of the Emma Press books, as another way of conveying the spirit of the book to the casual browser which will hopefully tip them over into buying the book. I want the books to feel friendly and welcoming, and to make it clear that we want them to be read, so I hope that the design and illustrations contribute to the accessibility of my books.

Who prints your books?

Emma: I currently use a local printer called Letterworks, but I’m always shopping around for others to try out too. We’re publishing our first full-colour book in November, so I need to find a new printer for that.

Could you describe your editing process? And how long does it take start to finish?

Emma: With the anthologies, Rachel and I begin by reading all the submissions through in our own time, and I label them rather cagily in my Gmail: ‘Maybe Yes’ and ‘No’. We compare our Maybe Yes lists and see if we need to restore any names, and then we read all the Maybe Yeses again and come up with a shortlist. Then we usually meet up and discuss the shortlist to decide on the final selection. Once we have the final selection and I’ve emailed everyone who submitted, we’ll meet up again to discuss edits to all of the poems and the running order of the anthology (which is very important to us), and from then on we do everything by email: I email back and forth with the poets until we’re all happy with the edits, and then I typeset the manuscript in InDesign and email back and forth with Rachel for proofreading edits.

It’s difficult to say how long this process takes, as it depends on how much time we have and also how many of the poems need editing. We did it in about 6 weeks for The Emma Press Anthology of Motherhood, working quite solidly, but it nearly killed us and I’m still very sorry for putting Rachel through that. In a more relaxed time-frame, it probably takes 3-4 months.

What’s your submissions policy?

Emma: I post all our call for submissions on our Submissions page, and I tend to give subscribers to our monthly Newsletter a head-start by revealing the upcoming themes a few weeks in advance. In March, I set up a concept called ‘The Emma Press Club‘, where poets have to buy a book from our website in order to submit to any anthology within the calendar year, and people who have already been accepted into an Emma Press book are Club members for life. For pamphlets, people have to be Club members and also buy a £5 submission fee ticket from our website for every pamphlet proposal they submit.

We run 4-6 calls for themed poems every year and two different calls for pamphlets, so I think it’s a good deal. I thought long and hard about whether we’d be excluding anyone with the Emma Press Club policy, but ultimately I don’t think £3.50 (for the cheapest ebook) is too much to pay for something fun, and it does actually mean the overall quality of submissions has improved, because poetry readers make better poets anyway. I feel no remorse about losing the opportunity to read poems written by people who can’t bring themselves to spend £3.50 on a book by the press they apparently want to be published by.

What are some basic mistakes people make when submitting to you?

Emma: I’m always very clear on the Submissions page about who will be editing each book, so I find it baffling when people write ‘Dear Sirs’ when the editors have so far only been female, or, once, ‘Dear Simon Jenkins’. Who is Simon Jenkins?

The other mistake would be ignoring our request for a covering letter. Some people just include their author bio and an attachment, or write ‘Dear Editors, Here are my poems, Regards’, which just seems rude. We’re not asking for a huge essay, and we definitely don’t want a self-exposing stream of consciousness, but when working on our shortlist we do take into account who seems rude and who seems nice, because we’ll have to work with them for a number of months.

Where do you look for new writers?

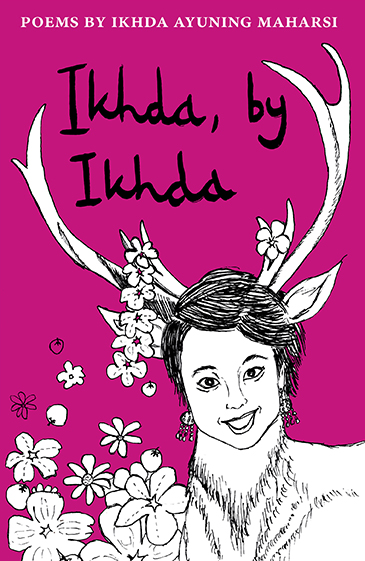

Emma: I send my calls for submissions out into the poetry-writing community, through places like the Poetry Library and the Poetry Society, and I also email round creative writing MA courses. I send the calls out internationally as well, as I’m very keen to work with poets overseas. The Australian Poetry organisation posted our first call for submissions for The Emma Press Anthology of Mildly Erotic Verse, which led to our encountering Melbourne poet Kristen Roberts, whose first pamphlet The Held and the Lost we published in February.

What advice would you give to poets today trying to get published?

Emma: One way to go about it would be to visit the Poetry Library journals and magazines section and try to work out which editors might like your style. Another tack would be to read more poetry by other people and to think about why it is good, as this will help your own writing improve and hopefully increase your chances of publication.

How do you pay your writers? How does remuneration work?

Emma: This year I’ve been paying anthology poets a one-off fee of £20, but I decided to stop because my anthologies contain up to 32 poets and it was going to get increasingly difficult to manage from a cashflow point of view. I could just do 1-2 anthologies a year instead of 5-6, but I think that would be a shame. From 2015, anthology poets will receive 3 complimentary copies of the book they appear in.

What is your approach to marketing and promotion?

Emma: I’m always thinking of how I can spend more time doing marketing and promotion. I guess my approach is ‘intensive and endlessly optimistic’. About once a month I’ll spend a furious week emailing out press releases and tweeting about my latest call for submissions or newest publications. I don’t have time to chase people up, so I just hope that enough people will respond or take action to make my campaign have some impact. I always approach a few wildcards just in case it’s my lucky day and Woman’s Hour want to discuss poems about motherhood or Alexandra Schulman from Vogue wants to give a tiny poetry publisher a break.

I’m always thinking about longer-term ways to promote my press and bring my poems to people too. Recently I set up Poem Club, like a micro book club, which I hope will help me to engage with people who like reading poems and don’t necessarily write them.

Do you make any money from publishing?

Emma: I fully intend to! This is my sole job, and I hope that I’ll be able to move out and be self-sufficient in the next year or so. Jamie McGarry from Valley Press is an endless source of inspiration to me in being able to support himself with his unfunded publishing business, and I firmly believe it is possible to make money from a poetry business.

If I’m to succeed, I need to focus on direct sales, at events and through my website. It’s lovely to have books on sale in bookshops, but given all the middle men involved in this process I only get about £3-4 from the sale of a £10 book, even before royalties.

What would help? Do you think the state or any other institution should do more for independent publishers?

Emma: It would be really nice if new entrepreneurs could get discounted rail passes for, say, the first 5 years of running their business. I spend a huge amount on travel and a discounted rail pass would really help with building my business across the country.

It would also really help if national newspapers and television programmes took more of an interest in the work of smaller presses and made more space for reporting on poetry and literature in general.

I think the state should subsidise the arts for as long as the arts need subsidising to survive, but I do also think that some organisations, such as independent publishers, ought to be able to support themselves as businesses. Since we’re in a situation where that’s not possible, then we need to consider why that is and work on improving that.

Do you work full-time as a publisher?

Emma: Yes, I do. I work 15 hours a day, 5-7 days a week.

What do you think is a suitable second occupation?

Emma: Maybe something that had helpful perks, like an admin role in a good launch party venue or at a high quality printer’s, or a high-up position in a train company.

Has your work suffered from a diversion of energy into other employments or is it enriched by it?

Emma: If I had a part-time job right now I think my work at the Emma Press might suffer, because it’s still at the very early stages and I need to be building momentum in order to make sure people remember the Press and feel excited about it.

Who distributes your books and where can I buy them?

Emma: I’m represented by Inpress, a sales and distribution service funded by Arts Council England. They represent lots of independent UK publishers to big bookshop chains and online retailers as well as independent booksellers, which means in theory you can order my books anywhere. I know we’re stocked in a few branches of Waterstones and Blackwells.

You can always, of course, buy the books directly from the Emma Press website.

Do you have any staff? If so, how many?

Emma: It’s just me at the moment.

Apart from books/pamphlets, what else do you make?

Emma: When we launched The Flower and the Plough and I wanted to encourage people to see the book as a good gift, I created some romance-themed postcards and greetings cards to sell alongside it, decorated with my illustrations and handwritten poems. People responded well to them, so last Christmas I created a set of ten postcards inspired by love poems: the ‘In Love with The Emma Press‘ set of postcards.

What other indie publishers do you like?

Emma: I think Sidekick Books are great. They produce amazing themed poetry anthologies and collaborative works, like Coin Opera I and II (poems about video games) and Angela (a weird, disturbing graphic novel/narrative poem about Angela Lansbury). I sold their books on the poetry stall I ran at Lower Marsh Market last summer, and people responded really well to the design and attention to detail in all their books.

I’m also a huge admirer of HappenStance, which produces elegant, lovingly-crafted poetry pamphlets, and CB Editions, which champions experimental writing.

But above all I admire Valley Press, which I mentioned before. Valley Press is based in Scarborough and was founded by Jamie McGarry just over five years ago. Jamie began it because he couldn’t get even an unpaid internship at a big publishing house, and the success of Valley Press proves that you don’t need to know very much about traditional publishing in order to start your own publishing operation these days. Jamie worked everything out for himself, and I think his business is all the stronger for it. He taught himself text design, cover design, web design, editing and business management, and he publishes some of the most exciting writers around, including John Wedgwood Clarke.

How optimistic are you about the future of independent publishing? Are you satisfied with your own solutions to the problems it currently faces?

Emma: I’m very optimistic. Having worked in one of the largest trade publishing houses, I can confidently say that the publishing industry is fully equipped to survive and flourish in the digital age: the only thing slowing it down is the people at the top playing it safe and holding on until retirement so they can enjoy their ridiculously large pensions. Independent publishers may be lacking in international distribution solutions and guaranteed reviews in the Guardian, but we also have the freedom to experiment and adapt as quickly as we like, and since we actually know who our readers are we can market directly to them. We can take risks because we don’t have enormous pensions and we can’t afford to buy houses.

The Emma Press Club is my solution to the apparent imbalance between people wanting to be published and people wanting to buy books, and I started Poem Club to reach more readers. The Emma Press and Valley Press became ‘engaged’ last year, which was a fun way of explaining our new arrangement where we bounce ideas off each other and share a blog, but also a way of emphasising the human aspects of our presses.

Do you have anything to add about e-books / Amazon / the Internet that hasn’t already been said a thousand times before?

Emma: I’ve just knocked back a literary device of a margarita – I’m in no state to be coming up with original thoughts.

What advice would you give to someone starting their own independent publishing business today?

Emma: There’s everything to play for. Big publishers have got too big and are floundering – they’ll probably all collapse in the next decade or so, hopefully bringing down Amazon with them, so you have every chance of being one of the gutsy indie presses which will crawl out of the wreckage and claim their rightful place at the forefront of publishing. Indie presses already are at the forefront of publishing!

As for more practical advice, go for coffee with as many people in the publishing industry as you can and try to form a sense of what your publishing house will stand for. You’ve got to have principles, or you’ll struggle to to make the right decisions for yourself. Also, go to indie book fairs like the Poetry Book Fair at Conway Hall in September and look at lots of books, by big publishers as well as smaller independent publishers, and think about what you like and don’t like about their production and content.

Tell me something about being an independent publisher that most people don’t know.

Emma: We need people to buy our books in order to keep us going.

Pub Talk aims to highlight the extraordinary amount of interesting poetry presses there are today, and the amazing work they do and the incredible writers they publish. We hope this survey will give poets and writers alike a greater knowledge of the independent publishing landscape as a whole, as well as providing a public forum where publishers can be honest, open and candid about publishing as a business. A few questions from this interview have been appropriated from Cyril Connolly’s 1946 ‘The Cost of Letters’ survey.

Came across The Emma Press a couple of months back and bought the Anthology of Motherhood. Love the format, the cover and the great poetry. The website is friendly and accessible and makes you feel you want to be a part of the venture.