No-one gets into poetry for the fame and riches. Frankly, most poets are regarded as viewing mainstream culture with suspicion, attracted as they are to the arcane world of collecting unusually-shaped pamphlets, conjugating gerunds and seeking out clandestine spoken word evenings in the backs of run-down Japanese laundrettes.

For many poets root, hog or die is part of the vocation, often the latter, thanklessly and without recognition. Alex MacDonald, however, believes the Internet is changing all this.

Like us, Alex is a lover of all things web and committed to the need to break down barriers and provide alternative spaces for new writing. So when we were thinking about who to choose for our second CAMPUS residency, Alex was the perfect choice.

We spoke to Alex about his upcoming residency and why there’s more to Internet poetry than plugged-in Prufrocks and zombie sestinas.

What can we expect from your residency, ‘This Twittering World’, and what are some of the ideas and guiding influences behind it?

Alex: Ideally I want to debate what role the Internet has had on contemporary poetry and how it is shaping our understanding of its history. For example, it offers today’s poet a global audience immediately, but it also gives platforms which can create exclusive poetic cliques, which can be counter-productive. What better place to have that debate than on the Internet?

The web has been a great influence on my work, not just because of the plethora of visual and textual stimulus which is outside of my immediate experience. It is taught me a lot about how people communicate with each other, what interests them and how they order/control the world around them, which can only be of interest to the curious poet.

How did you start writing poetry? And how would you describe the poetry you’re writing now?

Alex: I started by copying and trying to imitate the poets whose work I admired. When I read Eliot’s essay which said a young poet should do that, I felt like my time wasn’t wasted. I would often write from something – so I have a lot of photography and art books at home. I tend to do less of that now, although I still flick through Francis Bacon’s work for visual prompts.

These days, my poems are often about ideas, things I have seen in the news, interrogating them and bringing them to a logical end point. I’m interested in public speaking at the moment – lectures, religious decrees, cold calls on the phone. These, and their idiosyncratic quirks, are fascinating.

Your poems always have really great titles. What do you think makes a good title? Do titles ever come before the poems?

Alex: Thanks! I used to be a press officer, so the importance of titles has been drilled in to me – a good title would decide whether people read your press notice or not. I’m inspired by song titles. Sometimes they can be better than the actual song – like the band The Locust – but bands like Stars of the Lid have incredible music, made even better with the song titles.

I often think about titles while sketching the poem, the title remains and the poem isn’t finished for ages – I think this is a problem for other Poets. Recent favourites of mine which need more attention include “Man, I Feel Like a Million Women” and “This is Just to Let You Know That I Know Who You Are”.

There is this uneasy sense in your work that the physical, organic world is constantly only being reached by proxy, often mediated through screens, ‘TVs’, ‘the stage’, ‘adverts’, ‘video’ and ‘self help tapes’. I wonder if you could speak more on why this tension between art and life interests you?

Alex: I once asked a similar question to David Lynch at the UK premiere of Inland Empire (you can read it if you click here, my question is ‘Q3’) and he evaded it beautifully. I might not be as tricksy. There are a few things. I’m an only child, so I spent a lot of time with videos, watching and recording things off the TV. I find the visual culture of TV very interesting: talk shows, comedy programmes and the news all ‘relate’ human experience, but their form is a complete fabrication. And I’ve always been fond of the self-aware in Art – like Shakespeare’s asides, Vic and Bob’s comedy routines, that scene in Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (if you’ve seen it, you know which bit I mean). And, not to put too fine a point on it, but a poem itself is a proxy for the poet.

I really admire a poem you recently published on one of our CAMPUS groups – ‘Shibboleth’. Tell me more about it and the unusual form.

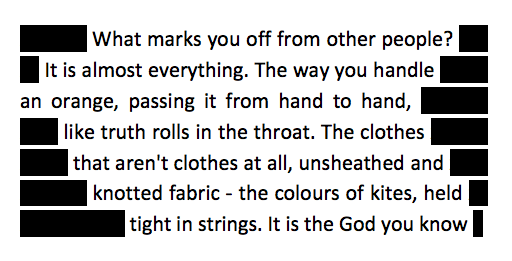

Alex: I’m really interested in the white spaces in poetry – like the bookmark style poems of Kay Ryan or Anne Carson’s Red Doc> and the fragmentary work of Emily Berry, Ahren Warner and Sarah Hesketh. ‘Shibboleth’ includes a lot of black lines. Here are the first 7 lines of the poem:

It obviously reverses the white spaces which are so frequent in poetry, and it often acts as a crack through the poem in a confined space. I’ll leave it to the reader to decide what else it does for them. Of course, the form is nothing if the poem isn’t any good, which is my main focus. The poem itself is part of a series I’m currently drafting about ‘being British’.

I know you love modernist poetry and the 20th century avant garde, which has left us a very fraught legacy with how we’ve now come to regard originality. How do you think our relationship with originality has changed, particularly since the Internet, and what tips can you give to those looking to productively react against the past and make language their own?

Alex: I’ve never let the thought of someone doing something before me get in the way of writing (Michael Donaghy’s first collection was called Shibboleth, for example). I thought what John Barth said, in his essay ‘The Literature of Exhaustion’, that using this ‘lack of originality’ as a creative vehicle itself was very interesting – I think that is being addressed a lot at the moment, and it is very exciting. But every voice is infinitely different from the one preceding it – I go to a weekly class with many talented writers, there is some cross over of topics, but each poet comes to their own conclusions differently.

Have you ever thought of yourself as a political poet?

Alex: Some of my work is overtly political. My Pussy Riot poem is political, ‘Reasons for Asylum Admissions’, which was a collection of real and fictional reasons why people were admitted into an American mental asylum in the 1800s, is less so, but deals with ‘political issues’. I am a political poet in the way that I’m interested in language, how people use it to differentiate themselves, how politicians use language, and where language is censored by the state. But my work’s not going to advocate donning a beret and throwing rocks at the Old Yard anytime soon – overtly political poetry is, often, quite ranty and not interesting. When politics is played in to a poem subtlety, it so more effective.

Take Harold Pinter’s late poetry. American Football is sweary, loud, boring, and there’s no need to read it again. But Weather Forecast, with such a great last line, brings in so much more, because of its normality and its vagueness, it is menacing, strange, unsure. Incidentally, his Nobel Prize speech is surely one of the best political writings of this century – I listen to it a lot.

What living poets could you recommend? Let’s be mean – pick 5.

Alex: This is tough because there are absolutely loads. So I will go over the most recent poets I have been reading and their work.

I have loved Sophie Collins’ poetry for a few years now, and I think her work is incredibly exciting. She recently wrote a poem from the view point of Selma from The Simpsons, and it is so amazing. I could read it forever.

Recently, I’ve been re-reading Oli Hazzard’s book Between two windows and he’s so inventive and interesting. He can be incredibly abstract and then deeply emotive within the space of three stanzas.

Emily Berry’s Dear Boy is one of the best poetry debuts I have read in years. So exciting – it won the Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection, and it totally deserves it.

If Rachael Allen and I were at school together I would hang out with her in the stairwells and swap new poems with her. Her work gets me incredibly excited about contemporary poetry.

And I am so lucky that I’ve seen a lot of the poems from Rebecca Perry’s first collection – Beauty / Beauty – that is coming out on Bloodaxe Books next year. It is beautiful work, and I can’t get enough of it.

What advice would you give a young poet today?

Alex: Read as much poetry as you can get your hands. If you have an idea, write through it. Read W.G. Sebald.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.