And to this day

there’s a well down those woods

that feeds off tales of stay aways.

By nine our heads were knitted with them:

fireside legends, the edges of seats.

Chewing our nails, twisting our hair,

we’d conker scout the outer trees

but soon slip deeper

to a cooler place, that well of stone.

A check over the shoulders then

leaning in, up to no good with echoes,

things we’d longed to say all day.

Once spent of shout, we’d itch to do.

The once we did. Pull up the bucket.

See who could hoist it full and quickest.

The straining rope, riddled with rot,

coiling onto our pumps, until, at last,

its weeping pail hauled over with a groan.

Us flat out on our backs, about to laugh,

but for the bit of finger there inside.

That lock of hair. The miles from home.

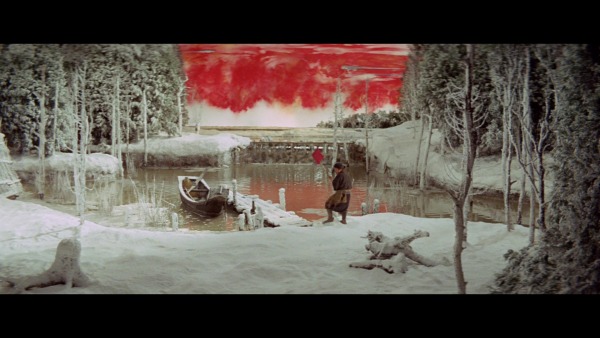

I started this poem fourteen summers ago on the Greek island of Paros. I know and remember this because it was our first ever family holiday by aeroplane and something spooky happened to all the photos we took whilst visiting the sacred island of Delos. I had just finished my GCSEs and, via H.P. Lovecraft, had discovered and been unable to shake off Algernon Blackwood’s ‘The Willows’ (1907) and ‘The Wendigo’ (1910), which are still two of the finest supernatural stories I have ever read. At a sleepover earlier that year, a load of us watched Hideo Nakata’s Ringu (1998) into the early hours, stunned by its building dread and jaw-dropping final sequence. There was no sleeping after that, but the success of Ringu in the UK did open up a whole other world of Japanese and Korean stories for me to find where the role and symbolism of water seemed to be saying something particular about the world beyond our own. Some years later, I came across Lafcadio Hearn’s translations of vengeful yuurei spirits in the east and Masaki Kobayashi’s cinematic masterpiece of the supernatural, Kwaidan (1965); all of these encounters had some tonal or conceptual influence on ‘And to this day’.

Ringu, dir. Hideo Nakata, 1998

Kwaidan, dir. Masaki Kobayashi, 1965

Back when this poem started itself, my granddad, who appears frequently throughout Primers Volume Two, had been working for nearly twenty years as a groundsman at Dudmaston Hall, an integrated agricultural estate just outside of Bridgnorth, Shropshire. Managed by the National Trust, it’s been kept together since medieval times and its woodland still preserves the ancient Forest of Morfe. As a boy, I remember exploring those woods while he was coppicing or marking trees; on the opposite edge of the lake, which was surrounded by vivid red arteries of dogwood, squatted an ominous brick boathouse, full of shadow, and never used. There was something awful about it; it tugged on my thoughts – and I didn’t go near it. In autumn, we’d sometimes walk up from my grandparents’ house in Broseley to Benthall woods, where we’d munch on sweet chestnuts, hunt for conkers, and peer from a distance at the C16th Hall that we were told had secret passageways and priest holes. I think Benthall and Dudmaston merged in my mind for the spatial terrain of the poem and its secret spaces.

Dudmaston Big Pool, Quatt, Bridgnorth

It’s clear that all of the above memories fed their fragments into the early drafts of ‘And to this day’. From looking at the piece of paper the first draft was written on, I can see how some words and images in the published version were there from the very start (the first four lines have changed little) but re-arranged into a different narrative sequence. The original title (‘The Well’) has changed to a run-on; other alterations have targeted verbs and nouns that are too specific or not specific enough, and extensive (and unconvincing) dialogue. It is impulsive and untamed, which I like about first drafts, but not yet settled into the couplets of the abandoned (I better not say finished) piece. I’m not sure whether to be chuffed or embarrassed by the fact that, though it’s been tinkered with for fourteen years, the nuts and bolts of the poem were written in under ten minutes.

Once typed up, which tends to be around draft 3, I usually print my poems out, scrawl the date on the back, and put them into a plastic sleeve in a ring-binder. I then (try to) leave it alone, and upon returning make edits in pencil on the page. I then make changes and print out the new version, which then goes in front of earlier drafts in the wallet. ‘And to this day’ was next looked at in the summer of 2004, where it started to settle itself out into two line stanzas:

Draft 4:

And to this day

there’s a well down those woods

that feeds off tales of stay aways.

Aged five our heads were knit with them:

fireside legends, the edges of seats.

When conker knocking we circled outer trees,

but soon slipped in deeper, four foot high.

Chewing our nails, twisting our hair,

trickling in with streams of noise

we’d break the spells and play on sunspots

where canopy gave up and moss clods steamed.

But, like drops to drain we’d roll downhill

to a warm, dark place: that well of stone.

A quick check over shoulders and we’d be at it,

leaning in, up to no good with echoes,

things we longed to say all day.

Once spent of shout, played pulling up the bucket,

see who could surface a full pot quickest.

I always won. Except once.

I heaved. Rope groaned and creaked,

wrung dry, then, just as I tired

it gave with a splash. Us flat on our backs.

We would have laughed,

but for the fingernail embedded in the wood,

the cord of hair. The miles from home.

Looking back at this version now, it is easy for me to hear where the pacing is really struggling and also where I (tellingly) have too much of myself in the poem, gesturing off in other directions at unhelpful moments: the jump from ‘I always won. Except once.’ to ‘I heaved’ seems to be one example of this. Other parts of this version are overindulgent for other reasons; at times it is prosaic and taking too long to get anywhere. The physical movement in the poem from outside the woods to the well seems to be juddering back and forth at least three times: ‘soon slipped in deeper’; ‘trickling in with streams of noise’; ‘we’d roll downhill’, which is distracting and not contributing much. Though I thought ‘moss clods steamed’ sounded and looked good, I also realised that it just wasn’t an honest observation – piled manure on a field might steam, but there was no persuasive enough reason for the bed of these woods to be steaming, or for the dark place to be warm rather than cool in its lack of light.

I often find when I am writing that ‘and’ becomes a petrol source in my lines: ‘and blah’, etc. I know that nine times out of ten I will be eking out metre by ear rather than having anything useful to add, and most likely repeating myself or undermining the impact of one word by stuffing in two. ‘Rope groaned and creaked’ in the above draft is a guilty case. I like ‘groaned’ and the echoing human voice it brings to the well but – does a rope creak? A floorboard might. The handle of a pail might. (We could also say that a rope doesn’t ‘groan’ but it is closer to conveying the physical weight of the water and its burden on the children). By this point, I think I knew that I wasn’t really writing a poem about a well, or what nasty things were inside it: that the more powerful charge is something connected to innocence lost and our inability to ‘unsee’ things that have happened to us, or others. Though an entirely different context, I now think of Heaney: ‘I was six when I first saw kittens drown.’ (‘The Early Purges’, Death of a Naturalist, Faber, 1966).

We scattered my granddad’s ashes at Dudmaston in 2006 and planted a lime tree there for him. Later, I discovered ‘This Lime-Tree Bower my Prison’ (1797), where Coleridge (with injured foot) is frustrated at being unable to follow his friends into the countryside but undertakes quite a powerful memorial reconstruction of the route: ‘I have lost / Beauties and feelings, such as would have been / Most sweet to my remembrance’. Returning to or even remembering Dudmaston is now a very layered experience, and its marbling of excitement and loss is one I wanted to try and explore in words.

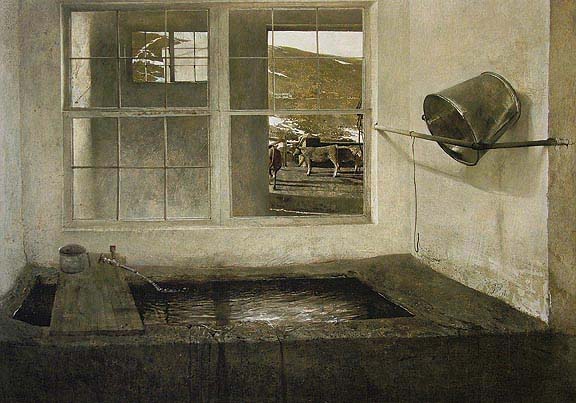

In 2015 I re-found ‘And to this day’ at the back of an old folder (behind rejection letters), having not looked at it for over a decade, and realised that it now also had something to say about the impact of suicide on me and my family – though from a certain distance, unlike some of the other poems in Primers Volume Two. I went through a series of drafts fairly quickly. Whilst in the US, I had stumbled across the moody Pennsylvanian landscape and window paintings of C20th American realist Andrew Wyeth (who, interestingly, inspired the production design for the American remake of Ringu); the body of water in Spring Fed (1967) felt particularly resonant with the well in my own poem, that had now come to symbolise more than I had intended when I started to write it after my GCSEs. I remember showing the poem to Paul Muldoon during a tutorial; he liked it and was very encouraging but questioned whether a few lines were ‘withstanding the pressure from without’. So, out they went!

Andrew Wyeth, Spring Fed, 1967, tempera on Masonite, Collection of Bill and Robin Weiss.

Draft 8:

And to this day

there’s a well down those woods

that feeds off tales of stay aways.

By nine our heads were knitted with them:

fireside legends, the edges of seats.

Chewing our nails, twisting our hair,

we’d conker scout the outer trees

but soon slip deeper

to a cooler place, that well of stone.

A check over the shoulders then

leaning in, up to no good with echoes,

things we’d longed to say all day.

Once spent of shout, we’d itch to do.

The once we did. Pull up the bucket.

See who could hoist it full and quickest.

The straining colon rope, rot-riddled,

spilling onto our shoes, until, at last,

its weeping pail slipped over with a groan.

Us flat on our backs, about to laugh,

but for the finger in its side,

that lock of hair. The miles from home.

I can see that the above version has very nearly arrived at the version I was finally happy to share. The middle section no longer dawdles around and the final sentence lands in the way I want it to. However, the ‘straining colon rope’ – as delicious as the disembowelling of a constipated well might be – is drawing too much attention to itself and detracting from the impact of the final couplet. Though I liked the echo from ‘spilling’ to ‘slipped’, the repetition of ‘slip’ grated on my ear and it didn’t feel the right verb to accompany a ‘groan’ either. When making final tweaks on this poem for publication, I received a useful editorial note about the possessive pronoun in the penultimate line – that it wasn’t completely clear where the finger was or to what the ‘side’ belonged. It was such a privilege and relief to have another pair of eyes on these poems; sometimes being so close to the writing is headache-inducing, especially when you can hear something isn’t quite working – when you can’t see the wood for the trees.

I now keep coming across great poems featuring wells: Wordsworth, Dickinson, Longley, William Stafford, Randall Jarrell. I had completely forgotten the well poem, Heaney’s ‘Personal Helicon’ (Death of a Naturalist), until I read Ciaran Carson’s haunting part-elegy and part-homage ‘In Memory’ (From Elsewhere, The Gallery Press, 2014). A haunted well in the latest issue of Acumen (No. 88) is my most recent discovery – please let me know @bransfield_ben if you have any others to recommend!

Though exploring memory, lived experience, and invention in a different way to my other poems, I enjoyed the long time spent writing and redrafting ‘And to this day’: it dredged quite a lot to the surface for me in the end. Thank you for reading it.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.