Welcome to our Forward Prizes 2025 ’How I Did It’ series. This year we asked poets shortlisted for the Jerwood Prize for Best First Collection to write about the inspiration behind one of the poems from their chosen collection. Here’s Michael Mullen on what inspired them to write the poem ‘Beithir’ in Goonie.

Any writer of Scots – who thinks, dreams, speaks in Scots – when faced with the blank page has a decision to make. Scots? English? Commercial? Parochial? Political? Gentile? And so on and so on. This sensation, this questioning, is not exclusive to Scots speakers, of course, but unlike other polyglots who are deciding either/or between languages/langwijeez when discussing Scots there is a difference. Scots doesn’t really work from a straight translation – Scots to English – so the writer must make more of a compromise than a choice. Scots is an impassioned, political, poetic, transmutable, amorphous thing with no homogeneous vocabulary, with thousands of regional differences. There are also micro-ecologies within this: Doric that is spoke in Aberdeenshire and Dundee, Norn in Shetland amongst others. Micro isn’t meant to say lesser but more to say different and thriving in a positively provincial sense. In a way, the fact that Scots hasn’t been homogenised or streamlined, I think, is its power, its beautiful uniqueness. It has only recently been recognised as a language as it is not completely different from English, in my opinion, but maybe more of a distant cousin.

To Capture Questioning!

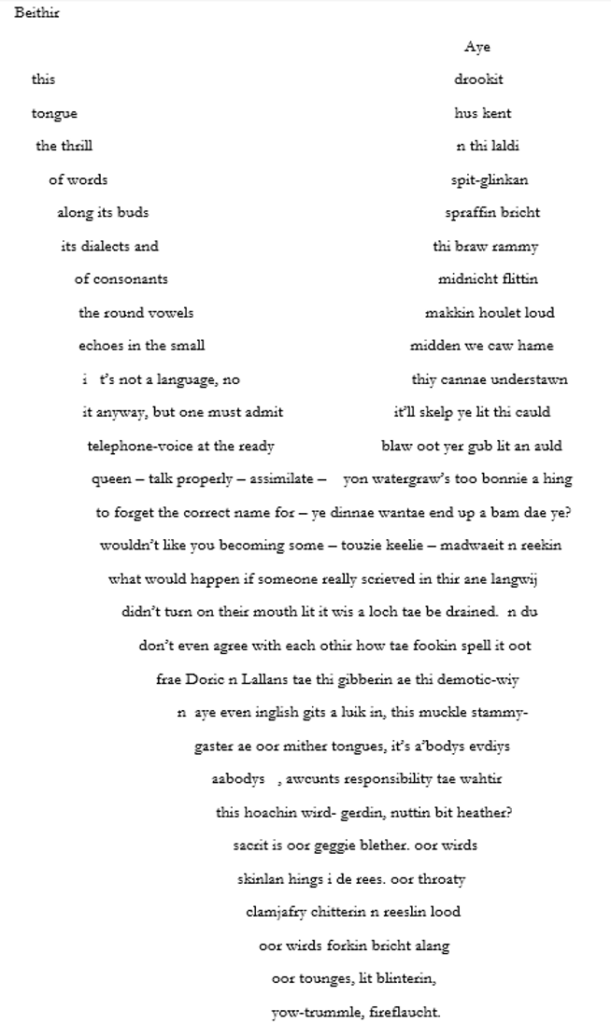

There are many facets of the argument not mentioned here, a long and storied history around the Scots language, on the poetry front, how do you capture this questioning? That is what ‘Beithir’ set out – rather ambitiously – to do.

The poet W.N Herbert’s T.S Eliot shortlisted collection Forked Tongue was a massive inspiration for the poem. When I first encountered Herbert’s idea of the forked tongue – a way to describe the split between Scots/English languages simultaneously poised together but with a flourish, a cleaving, a lexical hybridism – it instantly made sense. This image was so evocative and perfectly encapsulates Scots for me as a mutable, creative, code switching. I started to think of the shape – to mimic the forked tongue in a graphic concrete way. The literal split of the tongue made putting the Standard English on the left side of the poem as the correct, assimilated, commercial, understandable mode of speech obvious and then on the right I would have the Scots. Knowing that the split would eventually have to meet, I then thought about how the Scots and the English would meet on the page, just as they often do in speech. Once I knew the vague shape, I knew the poem would be too flat, too generic if it was just a sort of Glaswegian demotic Scots meeting English on the page. If the idea was English as the correct, established order on the page then the Scots had to disrupt that. How is this ‘disruption’ then achieved? Well, Scots has not only a long oral tradition used by the people but also a long creative lineage where writers have used it to mimic demotic speech. Also to connect to lost words, to stupefy, to reach an alternative consciousness of the spirit, to dislocate.

On Revival, & Disruption

The poetic titan Hugh McDiarmid wrote in a ‘synthetic’ Scots – a deliberately archaic form – where he mined and revived long-lost/obscure words such as watergraw (rainbow) and glinkan (glittering) blinterin (flickering). These words are not commonly used in many parts of Scotland but as McDiarmid had revived them, I also chose to re-revive them. Many of Goonie’s poems are about lionising and celebrating dead family but also cultural ancestors, the Scots giants on whose shoulders we stand. For me, all my poetry is a disruption of language and a séance. There are words and phrases skimmed from various other Scottish poets such as Sheena Blackhall’s Doric (stammygaster), Roseanne Watt’s Norn (i de rees), Rober Garioch’s Edinburgh Scots (touzie-keelie) and Tom Leonard’s alternative orthography (thi, wahtir, bit).

Myth & Deviation…

Originally titled ‘This Forked Tongue’ – I thought this was too similar to Herbert’s Forked Tongue – this was when the muccle, mystical beithir came in. A beithir is a serpent from Scottish/Irish mythology like a dragon or a wyvern but without wings or fiery breath. The beithir is much more connected to water and lightning, appropriately Celtic. It is also one of the words in Gaelic for lightning, another thing that forks, cracks, deviates. In one of the tales of the beithir, it was said that running to a body of water – a loch – would save you from the beithir’s sting and in other tales reciting a poem could spare you. These connections seemed so perfect for what I was trying to do and bringing in the mythical can’t help but make us look to the past, to our mighty tradition. Beithir is also very similar to the Scots word blether which means to talk. Words like yow-trummle (the sheep shearing season) and fireflaucht (lightning) connect us to the land, to our ancestors who must have herded in a muggy June and been faced with these bright phantasms of light. The very existence of the words, their own histories.

I thought of the speaker as the beithir, the old serpent who has watched us for years argue, diminish, abandon our own languages. It’s almost a cliché now in Scotland – the story of being told to speak properly by schoolteachers. Whatever that means. Is poetry speaking properly? What is proper? These are the things that whirl around the beithir’s mind before delivering their soliloquy, with hopefully as much honey as there is venom.

Michael Mullen is a queer poet, writer and spoken-word artists from Glasgow. Writing in both Scots and English, for the page and the stage. Their work has been featured in Gutter, Neu Reekie: Neu Voices, The Scotsman, Bella Caledonia and many more. Michael was the Scottish National Slam Championship runner-up 2022 and later a judge, their work has also appeared on Life and Rhymes with Benjamin Zephaniah on Sky Arts. Co-winner of the Edwin Morgan Poetry Award 2023-24 and winner of The List’sBest Rising Scottish Author. Their first collection Goonie was released with Little, Brown in June 2025 and was shortlisted for the Forward Jerwood Prize for Best First Collection.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.