Welcome to our Forward Prizes 2025 ’How I Did It’ series. This year we asked poets shortlisted for the Jerwood Prize for Best First Collection to write about the inspiration behind one of the poems from their chosen collection. Here’s Isabelle Baafi on what inspired her to write the poem ‘Piggy’ in Chaotic Good.

PIGGY

From Horror

The poem ‘PIGGY’ is about the scariest thing that ever happened to me, and one of the worst things I ever saw in person. I was fifteen or sixteen at the time, and part of a crowd that – I’m not proud to say it – had gathered to witness a fight between two girls who’d fallen out. It wasn’t until we got to the street where one of the girls (let’s call her Girl A) lived, and Girl B called her out, that it became clear how oblivious she actually was. She greeted Girl B like a friend. And in that moment, I realised with horror – as we all did, I’m sure – that it was not going to be a mutually planned fight but a spontaneous, surprise attack.

The whole thing lasted seconds, but I’ll never forget it: the look on the girl’s face, the jeering from many in the crowd, the barking dogs that her brothers unleashed on us, the panicked, scattering onlookers, the seemingly endless road we ran down, the dual carriageway where the police caught up with us. They confiscated all of our phones, suspecting that some had filmed the attack (at the time, ‘happy slapping’ – in which an unsuspecting stranger was smacked as others recorded the assault – was a sickening trend).

In Search of Answers

Over a decade later, during my creative writing MSt, I was given an assignment to write about an event from different points of view and I chose this one. The sequence features six poems which examine the event from the perspective of each of the girls, as well as the crowd, the brother(s), the police and a neighbour. The sequence’s title, ‘P___Y’, is a reference to Hangman, and the game’s challenge to search for the ‘right’ answer in the midst of the looming possibility that it may never be determined. I knew that I wanted one of the poems to be in the voice of the police who had questioned us; the people who (as experience and history had taught me) hardly viewed us as people.

When I was 14, I went to a house party in Camberwell and saw two small Black boys – no more than four or five years old – playing in the hallway. In a flash, one of them pinned the other one’s arms behind his back and shoved him up against the wall before patting his legs. And I thought to myself, how do they already know what that looks like? How many times have they seen it for them to be able to do that so accurately? It broke my heart. This was just a few years before the killing of Mark Duggan – which led to the 2011 riots – during a time of escalated stop and searches, disproportionately targeted at Black youths.

W.E.B. Du Bois talks about double consciousness in his book The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and there are many ways in which it manifests. One is Black people’s simultaneous awareness of our need for protection whilst living in a world that not only perceives us as the threat, but in fact designs it’s forms of ‘protection’ with our destruction in mind.

The Third Utterance

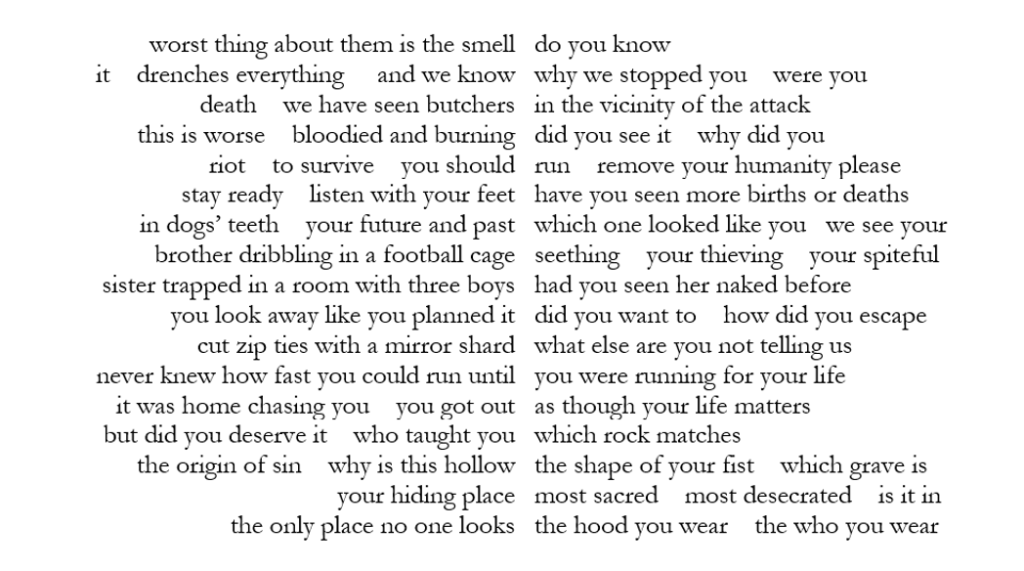

Perhaps partly for this reason I also wanted the poem to be a contrapuntal. I’m fascinated by the idea of two separate utterances existing side by side, which, when interwoven, create a third utterance, a third truth. The first time I came across a poem like that was in Tyehimba Jess’s Olio (2016), an ambitious book exploring the voices and lives of African American performers after the Civil War. The collection skilfully features numerous instances of interwoven voices, such as Mark Twain and Blind Tom Wiggins, John Berryman and Henry ‘Box’ Brown. Likewise, in ‘PIGGY’, I wanted the police’s collective voice to be dissected by and intermingled with that of the crowd – who would expound on what it means to be young and Black and to live in fear of police brutality, speaking back to and commenting on how we felt (feel) and were (are) systemically treated.

Eventually, I decided that the duality would work best if the police’s side was comprised entirely of questions, with some being the typical questions that one might expect from law enforcement:

do you know / why we stopped you

why did you / run

Others are more poetic, reaching for deep truths and existential, moral, epistemological forms of understanding:

have you seen more births or deaths

which rock matches / the shape of your fist

do you kill the spiders you catch

However, not all of those questions made it into the final draft.

Tackling Tricky Form

The contrapuntal form can be tricky. In fact, any form in which a precise phrase is intended to open up into multiple subclauses typically is: English grammar is not always so flexible. I abandoned the poem and came back to it numerous times. At one point, it was exclusively questions, but I knew that, although the police had inspired the poem, I didn’t want them to be the only voice.

I decided that if the police’s side was going to be all questions then the left side would be entirely (or at least almost entirely) statements. But not so much a ceding to interrogation as a defiant mode of self-assertion. And so the right, the police, would speak accusation, hatred and threat, and the left, the young people, would speak warning, wisdom, reflection, hope and regret.

riot to survive

stay ready listen with your feet

you look away like you planned it

why is this hollow / your hiding place

A Third Mood

On reflection, I imagine I took inspiration from Dionne Brand’s The Blue Clerk (2018), a stunning book of ars poetica prose poems in which the agendas and omissions of Western historical narratives are interrogated through an extended duologue between two characters: ‘the author’ and ‘the blue clerk’. The blue clerk is keeper of the author’s ‘left-hand pages’ (her unfiltered thoughts, unexpressed emotions and unsorted memories).

It is almost impossible to imagine agreements between the imperialist agenda (and its offshoots) and the Black, urban, working-class experience. But through the intermingling of the left side’s indicative mood and the right’s interrogative one, the poem gives way to a third mood, a subjunctive mood, reflecting on what was, what is, what is yet to be and what is bound to be – all at once:

to survive you should run remove your humanity

in dogs’ teeth your future and past which one looked like you

never knew how fast you could run until you were running for your life

you got out as though your life matters

Truth?

I wrote the questions on the right-hand side first and tweaked the line breaks so that the right column’s end words could lead into the left column’s second line and the right column’s second line, whilst also ensuring that the left column’s second line and the right column’s second line could lead into each other. And so on. Multiple connections, multiple truths, rippling out in numerous directions at once.

But isn’t life like that? Cause and effect. Agency and responsibility. Choice and culpability. We may choose column A, but sooner or later the consequence will spill into column B. And when that happens, we can’t always know whom we’ll have to answer to – whether ourselves, our peers, our kin, the powers that be or a Higher Power – or if our truth will be sufficient.

Isabelle Baafi is the author of Chaotic Good (Faber & Faber / Wesleyan University Press, 2025), which is a Poetry Book Society (PBS) Recommendation, and Ripe (ignitionpress, 2020), which won a Somerset Maugham Award and was a PBS Pamphlet Choice. She won First Prize in the Winchester Poetry Prize 2023 and Second Prize in the London Magazine Poetry Prize 2022. Her writing has been published in Granta, the TLS, The Poetry Review, Callaloo, The London Magazine, and elsewhere. She is a Ledbury Poetry Critic and an Obsidian Foundation Fellow. She edits at Poetry London and Magma.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.