Welcome to our Forward Prizes 2025 ’How I Did It’ series. This year we asked poets shortlisted for the Jerwood Prize for Best First Collection to write about the inspiration behind one of the poems from their chosen collection. Here’s Catherine-Esther Cowie on what inspired her to write the poem ‘Mimorian’ in Heirloom.

In Another Language

‘Mimorian’ is a surprising outcome of my desire to improve my Spanish speaking and reading skills. A few years ago, the library close to where I currently live offered a poetry class that would not only examine poetry by South American authors but would be conducted entirely in Spanish.

I hadn’t spoken Spanish in ten years but thought to myself, why not. Wouldn’t it be something to write a poem in another language?

Of course, the class turned out to be more challenging than I expected. Like most people trying to master another language, my understanding was better than my speaking. But in my study of South American poets, I discovered the Brazilian poet Carlos Drummond and the English translation of his poem ‘Resíduo’. I liked how several of the lines in the poem began with the preposition ‘Of’ which hearkened to my earlier attempts to successfully write a poem that used a preposition as an anaphora after reading Paul Celan’s ‘Zurich, the Stock Inn’.

Beyond Craft

But beyond the craft element, Drummond’s poem explores the residue that persists as we live our lives: our anger, our fear, even the minutiae of everyday life. His poem provided a scaffolding for me to explore themes of inheritance and memory in my own work – what lives on after a traumatic event, after a person has passed away. What stories or memories persist? What little remains? And what potency resides in the little that remains?

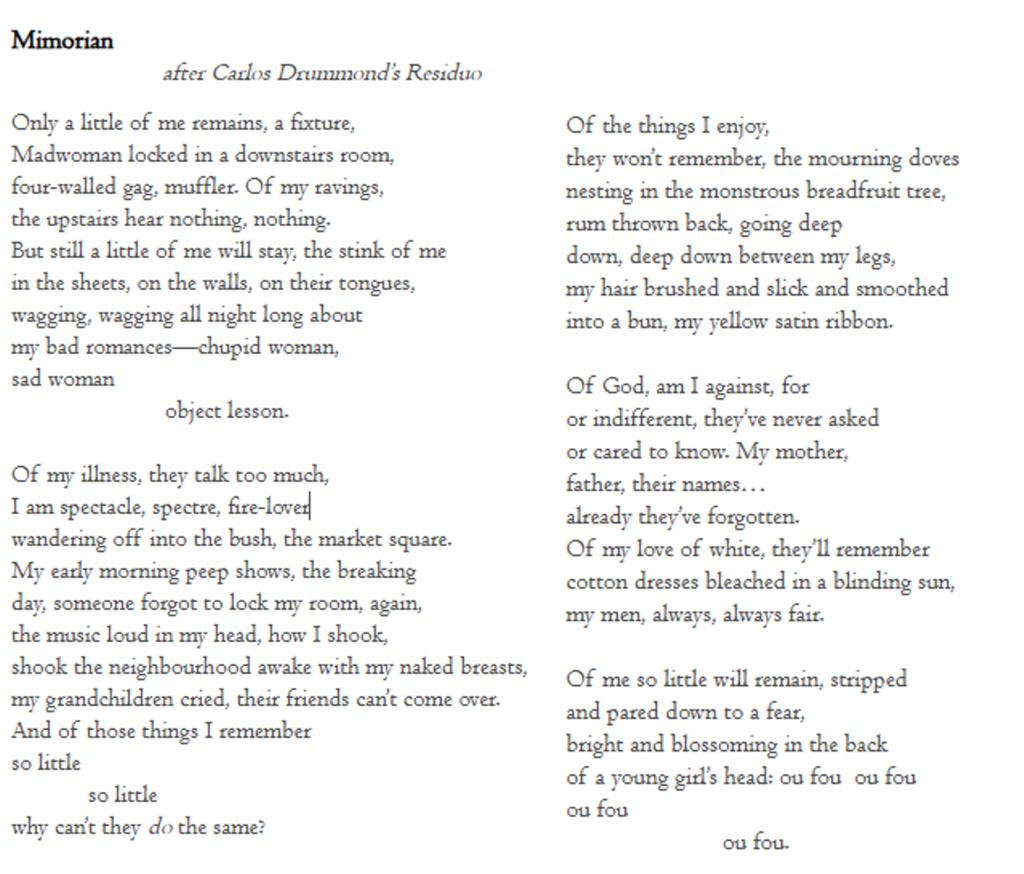

‘Mimorian’ examines how what we remember can flatten a person into an illness, a victim of abuse or a bad romance. Sometimes the challenge when writing work that explores trauma, is that the trauma is all that is said about the person. I wanted the speaker of the poem to speak back to this memory of herself. Persona provided the vehicle for Leda, the speaker in the poem, to challenge what is remembered, what is left unsaid about her.

What Remains…

I began writing the poem from that impetus, ‘a little of me remains.’ I started to list out what would remain from the persona of Leda. What would her life look like? What would people say about her? What would she say about herself? What would she want people to know? I pulled in details that would make sense for someone living on a Caribbean island as well as what I remembered from my visits to St. Lucia, ‘the mourning doves, / nesting in the monstrous breadfruit trees.’

On Form, & Forgetting

In constructing the stanzas, I used ‘of’ as an anaphora to guide the reader through the emotional landscape of the speaker. For example, one of the lines in stanza one begins with ‘Of my ravings,’ and then the reader is confronted with the speaker’s frustration at her current abode. She calls the room, ‘four-walled gag’. Stanza three begins with ‘Of the things I enjoy’ and Leda describes the things that give her pleasure and joy, ‘my hair brushed and slick and smoothed / into a bun, my yellow satin ribbon.’ Ultimately, the reader is confronted with the speaker’s loss. Memory has and will fail to preserve or carry the weight of who Leda is as a person.

Yet, this persistent act of remembering ‘so little’ causes harm not only to Leda but to future generations. I imagined this defective memory taking on a life of its own and becoming a ghost – a haunting, ‘…a fear, / bright and blossoming in the back / of a young girl’s head’.

This Haunting

I wanted to reflect this haunting and its impact on a future generation whose knowledge of Leda is dependent on memory. The decision to use the Kwéyòl translation of ‘you are crazy’ – ou fou – was primarily based on the repetition of the ‘ooo’ sound that makes up both words. Why not repeat this sound three more times to better reflect a haunting.

Further, weaving Kwéyòl into this poem is reflective of my efforts in the book to represent my and perhaps other St. Lucian’s experience with language – the dominance of English in our society but the persistence of Kwéyòl which shows up in the middle of a conversation being conducted in English, in some of our folk songs, or in the intimacy of a familial setting.

Catherine-Esther Cowie was born in St. Lucia to a Trinidadian father and a St. Lucian mother. She migrated with her family to Canada and then to the USA. Her debut poetry collection is Heirloom (Carcanet Press, 2025) which was shortlisted for a Forward Poetry Prize. Her poems have been published in PN Review, Prairie Schooner, West Branch Journal, The Common, SWWIM, Rhino Poetry and others. Cowie is a Callaloo Creative Writing Workshop fellow. She lives in Illinois, USA.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.