In this installment of interviews with poets and performers who have combined poetry with other media we hear from actor Robert Bathurst, who is staging and starring in a double-bill of Christopher Reid’s A Scattering and The Song of Lunch at the Chichester Festival; Jacqueline Saphra, poet and poetry school tutor whose book If I Lay on my Back I Saw Nothing But Naked Women just appeared from the Emma Press; poet and poetry school tutor Simon Barraclough, who has developed many multimedia projects over several years; and poet and performer Ross Sutherland who has been creating live literature since 2004.

ROBERT BATHURST on Love, Loss and Chianti

Actor Robert Bathurst’s TV credits include Cold Feet, Downton Abbey and Toast of London. On stage he’s appeared in Three Sisters, Whipping It Up, Hedda Gabler, Present Laughter, An Ideal Husband, and a world tour as Alex the cartoon banker. He has also worked in radio and film, appearing recently in Mrs Brown’s Boys D’Movie.

My interview with Robert Bathurst took place by Skype. He discussed Love, Loss and Chianti, a double-bill of Christopher Reid’s prize-winning collection A Scattering and narrative poem The Song of Lunch.

Kathryn Maris: What was your motivation in not only staging A Scattering and The Song of Lunch but including animations. That is, what did you think a multimedia approach could add to the original works by Christopher?

Robert Bathurst: Any presentation has to put the writing first, and no amount of production should swamp that. Often theatre gets in the way of the words. Flash, startling and exciting imagery in theatre very often knocks out the language, and that should never be the case.

But what you also need in theatre is to give people treats, to make people glad they came to see a work as opposed to staying home and reading it. I felt that these two pieces, A Scattering and The Song of Lunch, would work well as a double bill because they are both, to my mind, very dramatic. The sort of treats I’m planning will give each half a different artistic thrust. For A Scattering I have added a setting by composer Tom Smail for Viola and cello. Tom perfectly captures the emotional complexity of the piece. It is only occasionally underscored and there are longer pieces between the main sections. The music in combination with these interludes adds to the meditation on grief that runs through the work.

We will also have a set which looks like strewn paper, as well as a screen that looks like an irregularly shaped book. On that screen in A Scattering there will be abstract images, but I’m also experimenting with using Christopher’s own writing because he uses coloured pencils when he inscribes books, and refers to his ‘crabbed hand’ in The Scattering. So I’ve got him to write down the title of the poems that have titles—not all of them do—which I hope to have projected on to the screen. So A Scattering will have not only a visual aspect but also a sound and music aspect.

In The Song of Lunch piece, by contrast, which is a two hander, I’m going to have visuals: cartoons by Charles Peattie, with whom I did the Alex-the-Banker play. Although Charles is well known for his Alex style, he’s taking on a more classical approach for this performance. That’s because about a third of the way through writing The Song of Lunch, which is about a disastrous date at an Italian restaurant, Christopher Reid realized he was telling a version of the Orpheus myth. There is an attempt to retrieve a woman from the ‘hell’ of her marriage. She, of course, doesn’t see it that way, rejects him, and he drinks too much and falls asleep when going to the gents. End of a relationship. Because the Orpheus theme runs through it, Charles (the artist) is looking at using silhouettes in the style of Greek pots. It’s going to be startling, but the key is for those images to not get in the way of the words. So we have to find a way to balance the images with the words. These images don’t distract the eye as a detailed drawing would, but they give an impression on what is going on in the speaker’s mind. The balance, if we get it right, will excite and engage the audience. I’m taking it to a mainstream theatre audience in Chichester, where there are 300 plus seats. Gregory Clark is the sound designer. He will do an abstract soundscape in the first half and a more literal one in second half to reflect street noise and restaurant sounds.

KM: What do you think an actor can bring to a poet’s work? Are there instances when you feel actors have not done poets’ work justice. If so, what were their mistakes?

RB: A temptation when performing poetry is giving it a ‘poetry voice’ or a poetry tone: overly respectful. You sound like a royal correspondent outside Buckingham Palace telling us bad news. You don’t need to have that sonorous tone just because something is in verse. A performance needs to connect with the words, rather than having a sort of ‘wash’ that tells people they’re in the presence of great writing. You have to deliver the writing and deliver the character. Of course people read poems differently; each style can be different but it has to be engaging.

One of the potential challenges of performing verse to mainstream theatre audiences is that people are afraid of poetry, afraid that they won’t understand it. To some extent the way that poetry is performed is the cause of this prejudice. Christopher’s writing helps because part of my aim is for people to leave theatre having not been constantly aware that they’ve been listening to verse. Poetry states things in ways that can be above prose, often clearer than flabby prose: taut and immediate. There’s every chance an audience could and should be engaged.

KM: Would you like to do more poetry-based performances in future?

RB: I’ve been offered a slot in New York after Chichester. Possibly Australia too. I’d like to do a tour round the world like I did with the Alex play. But this production is in its very early stages. I’m ambitious for it, and it might be that it doesn’t work. When the funding bodies who have given me grants to develop the show asked whether it had artistic risk, I said, ‘It’s staging poetry! What’s riskier than that?’

That said, mainstream audiences are very happy to accept verse. It’s called song lyrics. It’s not a new thing to put music with words. Crossing disciplines seems to me a logical thing to do. The important thing is engagement. It’s all about taking an audience and swinging them along.

I view a theatre ticket as a contact between author and audience. Anything that engages the audience wholly in what the author is trying to deliver has to be worthwhile.

JACQUELINE SAPHRA on If I Lay on my Back I Saw Nothing But Naked Women

Poet Jacqueline Saphra talks about If I Lay on my Back I Saw Nothing But Naked Women and the process of collaborating with a visual artist, and then performing the piece with musicians. Our conversation took place by email.

KM: Tell me a bit about your book, and how the multimedia approach came about?

JS: Like the process of writing my most successful poems, the project grew itself. It began as one prose poem, and enlarged to two, then more over a period of years. There was much putting in the drawer and taking out of the drawer, a lot of revisions, removals, additions, re-instatements over those years, and also some workshopping.

Once I felt I was on the way to a genuine sequence (and I’m always a bit suspicious of myself when I think I am), I had a feeling that I wanted an illustrator – it felt like an adult picture book to me. I had no idea which publisher might be interested, so it stayed in the drawer. Until The Emma Press asked for submissions of pamphlets. I knew they liked to have illustrations in their books, had a strong aesthetic, that they would do something beautiful and that the quality of the product would be excellent. That felt important.

Luckily for me, Emma Wright [of the Emma Press] liked the sequence and had a vision for the book as a picture book shape (square) rather than a pamphlet shape and a publication date was agreed. Some time after that, Emma sent me a couple of Mark Andrew Webber’s prints and I knew instantly that they’d be perfect for the book. He does lino cut prints from life drawing, and I spent an incredible afternoon with him in his studio in a dreamy kind of collaborative process. I’d read a poem to him and he’d respond rather like a medium: ‘I’m getting blue … a blue square … and a flower. Some kind of flower …’ That type of thing.

A couple of months later, print after gorgeous print emerged from his studio and Emma turned it all into a book.

Meanwhile, Emma mentioned her friend the cellist Alice Hyland, who’d performed children’s stories accompanied by the cello: might that be a worthwhile addition to readings from the book? My background is in theatre, so the idea of live collaboration fills me with excitement. Naturally I said yes. Then I thought of Benjamin Tassie, an up-and- coming young composer, and asked him if he’d write some music. He was keen, and suggested the music should be for both piano and cello.

You see how it happened? Just organically, without prior planning, the project found its way. Just like a poem.

There is probably more to come. Perhaps some visual elements, a director perhaps. Who knows?

KM: Do you find something limiting about conventional, old-fashioned ‘poetry readings’?

JS: I love conventional poetry readings if well done. But if well done. It takes effort, hard work and a certain amount of guts for a poet to inhabit their poems while reading them. It’s not that I want a big performance, just that the best readings for me are when the poet is connected to their own poem, and looks as if they really want to communicate it to their audience. Examples? Recently I’ve been blown away by Robert Hass, David Constantine, Naomi Shihab Nye, Warsan Shire, Kei Miller, Liz Berry … I could go on.

KM: Is the project funded?

JS: The project is unfunded at the moment, but we will be looking for some funding to further develop it. I’m extremely fortunate that my collaborators have been willing to contribute their considerable talents and time for nothing. I would like to be able to pay them!

KM: When and where has it be performed?

JS: The first performance was at The Poetry Cafe on Monday 24th November as a celebration of Mark Andrew Webber’s exhibition of prints. Another happened at the Torriano Meeting House on Sunday 30th November. We hope to arrange some readings at festivals next year. And we’re open to invitations!

SIMON BARRACLOUGH on Sunspots

Simon Barraclough was born in West Yorkshire. His debut collection, Los Alamos Mon Amour was published by Salt in 2008 was short-listed for a Forward prize. He has also published a pamphlet Bonjour Tetris with Penned in the Margins and a second full collection from Salt, Neptune Blue, in 2011. His third full length collection, Sunspots, is due out in the spring from Penned in the Margins. Here Simon talks about some of his collaborative and multimedia projects including Psycho Poetica, The Debris Fields and Sunspots.

Kathryn Maris: You have done several collaborative and multi-media projects. Can you take me through them and tell me a bit about each one?

Simon Barraclough: The first complex piece was Psycho Poetica, which debuted in 2010 to mark the 50th anniversary of Hitchcock’s seminal thriller. I’d written about Hitchcock (and indeed Psycho) before but I wanted to celebrate this important film in a more public, more inclusive manner. I spoke to the British Film Institute about it and they were interested but I didn’t hook them until I’d hit upon the format of slicing the film into twelve segments and allotting these segments randomly to 12 poets. I asked the poets to write a poem in response to their segment and between us we would read the 12 poems together, without titles or intros, to present a ‘faithful distortion’ of Psycho.

Given the importance of Bernard Herrmann’s score for Psycho, it dawned on me that we needed a musical element and I had just seen Oliver Barrett playing music for Chris McCabe’s Shad Thames, Broken Wharf, so I asked him if he’d like to compose a Herrmann-esque overture for the show. Thankfully he leaped at the chance and eventually we agreed that he would score the whole piece, and provide a musical interlude too. The music, and the live string quartet, was the thing that made the whole performance more theatrical and coherent and we went on to perform it at several exciting venues like the Whitechapel Gallery, the BFI, the Royal Festival Hall and Latitude.

In terms of funding, I received support from the BFI, the Whitechapel Gallery, Latitude, Tilt, and various other venues. Over time we presented ‘portable’ versions of the show, with pre-recorded music and only three readers, and I even performed a one-man version.

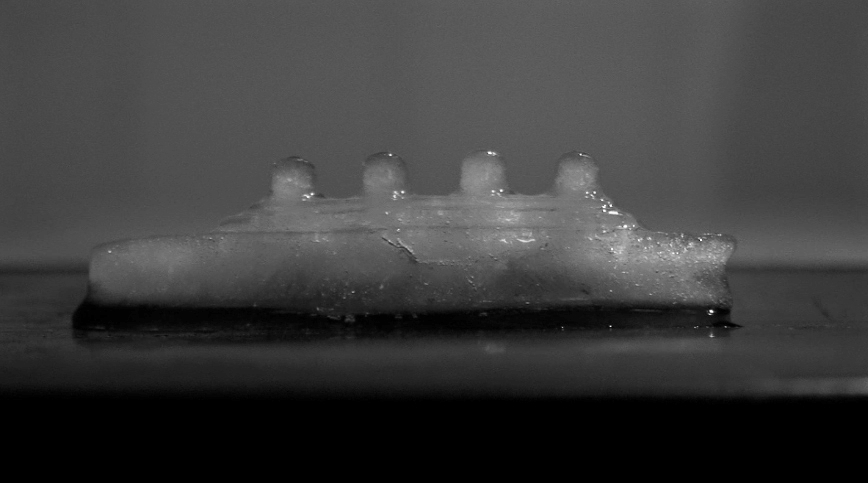

Heartened by the success and enjoyment of Psycho Poetica, I was thinking about what to do next when a lunchtime chat with Isobel Dixon in 2011 led us to the germ of an idea to write about the Titanic, whose centenary was coming up. This would become The Debris Field. Again, we wanted something public and performative but also something a little tighter and logistically simpler: Psycho Poetica, with 12 poets and four musicians, was great fun to perform but such a large ensemble is obviously tricky to manage at times.

So we decided to go with three voices and we invited Chris McCabe to join us, because he’s a brilliant writer and performer but he also has passionate links with Liverpool, where Titanic was registered. We wanted to write an oblique, immersive piece and strongly felt that music and film were necessary for the experience. So we went back to Oli Barrett and we hired film-maker Jack Wake-Walker. Again, the whole piece is scored and the three voices intermingle over the images. When we premiered the show on April 12th, 2012 (100 years to the night since the tragedy), the three performers read from the back of the room while the audience focused on the film. It’s a kind of ‘live cinema’.

Again, we received funding from the BFI and subsequent venues like Rich Mix, Bluecoats in Liverpool, and the Ledbury Festival.

KM: Can you tell me why a multimedia approach seemed to suit these projects? Why not just a pamphlet or an anthology or a book? Do you find the conventional poetry readings limiting?

SB: The reason these events lent themselves to more theatrical or multimedia presentation lies in the subject matter, I think. Cinema is obviously a discrete art form that has the potential (perhaps even the desire) to synthesize all the other arts, and it was important to me to create a multi-layered work that would reach beyond the page and also (we’re trying to sell tickets here) to different types of audience. I think we attracted fans of Hitchcock, of cinema, of poetry, and of contemporary music.

With The Debris Field, we wanted an immersive experience and to play on the rich tradition of representations of the disaster. We also wanted to ‘disappear’ as writers and performers, so ‘hiding’ behind the film and the music was a way of making sure that the piece was ‘not about us’, but about the event and the people caught up in it. Both Psycho Poetica and The Debris Field did eventually come out as books (from Sidekick Books) but not until the live events had had several airings. Performance does create the desire for a readable, portable version: every show we were asked if there were books available.

KM: Can you tell me a bit about your current project, Sunspots?

SB: My current project is Sunspots, which is both a book and a show. Again I’m collaborating with Oli and Jack but this time I’m co-writing the music, playing some trumpet and singing. It’s a natural extension for me from The Debris Field (in which I sing a snatch of re-purposed Brecht at one point) and is certainly something that will stretch me. The book is obsessively focused on the Sun and for me the Sun is uncontainable on paper alone. It’s a visual poem in itself and is a grand symphony of myth, symbolism, meaning, and science.

I’ve been working on Sunspots since 2011 and it never occurred to me not to make it into some kind of performance. The book is much longer than the show, so I’m extracting and ordering key poems into the event’s ‘narrative’ and turning five of the poems into songs with films. In effect they’re five music videos linked by elements of spoken word, silence, light, film, and music. It should be ready to go in spring, 2015. Sunspots is very kindly supported by The Arts Council.

Other things to be said about multimedia collaborations is that they’re fun, they’re challenging, they broaden your artistic palette, and they are a nice counterpoint to the more solitary side of the writing life, as enjoyable and important as that can also be.

Here is a link to a song from Sunspots, ‘Photon’: http://vimeo.com/92022722

ROSS SUTHERLAND on Stand By For Tape Back-Up

Ross Sutherland has four collections of poetry, all published by Penned In The Margins. Ross is also a member of the poetry collective Aisle16 with whom he runs Homework, an evening of literary miscellany in East London.

He has written several pieces for the stage. His new show, Standby For Tape Back-Up, will be on tour in late 2014/2015. He also has a documentary about whether computers will ever be able to write poetry. ‘Every Rendition On A Broken Machine’ can be watched at every-rendition.tumblr.com.

I interviewed Ross by phone.

Kathryn Maris: How long have you been combining poetry with other media and how did it start?

Ross Sutherland: I’m part of a collective of writers called Aisle 16, which has evolved over time and has had different members. Only Luke Wright and myself have consistently been in the collective. Our first ‘live literature’ show was in 2004, which was our third time at Edinburgh Fringe and pre-Fringe. Nowadays high-profile poets have shows at Edinburgh, but there was hardly any poetry at the Fringe back then, aside from a couple of cabaret shows. It was brutal for us to try to sell a poetry show. We’d spend five hours handing out flyers, only to attract a very small audience. We wanted to expand what could be included in a poetry show, in order to bring in more of an audience. So we decided to build in theatrical elements. It was a pragmatic decision.

Our first multimedia show was in 2004 and was called PowerPoint. We played the parts of motivational speakers in a corporate environment, using exaggerated corporate jargon, with Microsoft PowerPoint slides in the background. You could say that PowerPoint itself is almost a form of surreal poetry. Every poem had anywhere from twenty to seventy PowerPoint slides accompanying it. We were young to performing, so the visual element was useful, particularly for comedy: the screen is the comedian and you are the straight man. It’s a very classic style of humour that goes back to vaudeville. What we discovered over the course of writing PowerPoint was that we cold drop sentences from the script into Google and do an image search, thereby coming up with enough images to inundate the audience. For example, the phrase, ‘supporting the underdog,’ when entered into Google images, gave us a picture of someone standing on a dog. Google did the work for us, so the show was actually written with the collaboration of Google.

KM: What are you working on now?

RS: I’ve just done a piece called Stand By For Tape Back-up using found footage from an old videotape that belonged to my granddad. I’d watch a second of video and then write a line of poetry, syncronising the writing with what I saw on screen. Usually a metaphor has two parts: the tenor and the vehicle. The tenor is the subject and vehicle is the object that is used for the purposes of comparison. When you do things that have a visual component, you can have the tenor and vehicle exist simultaneously in a way that doesn’t happen as immediately in a text. The audience has to recognize, quickly, the cognitive dissonance between what I say and what I show them on the screen. The visual element adds an extra layer to the poem. Again, I become the straight man. I can speak to the audience in a plain, deadpan way, while the screen becomes the poet, taking my language and doing this alchemy with it, creating these multilayered metaphors. I love that process, which I think relates to neuroscience, specifically the way the brain recognizes and processes images. Usually the ‘visual’ part of the brain overpowers us, like when our attention is drawn to a TV in the corner of a pub. Recognizing the power of the screen and playing with its power is fascinating to me.

KM: Who does your work most appeal to?

RS: It may sound like a cliché, but younger people are more used to multitasking and jumping between media than older people, so they tend to respond more positively to being barraged with images while listening to a poem.

KM: How has your work been funded?

RS: It’s hard to fund these bespoke productions, so it is a slow process. I’ve had small commissions along the way, and some funding by Mercy in Liverpool and Penned in the Margins. Also I make things for free.

KM: How many projects have you done in all?

RS: About ten or eleven. Some were more successful than others. There’s a DIY aspect to my work. I like poems that are made quickly and have a spur-of the moment-feel, which are temporal and raw.

KM: What’s your preferred term for what you do? Live Literature? Multimedia poetry?

RS: Subject matter interests me more than defining the genre, so I define it differently depending on the show. I’m interested in the border between ‘poetry’ and where poetry becomes something else. When I do a show, I want two percent of the room to be thinking, ‘That’s not poetry. You killed poetry.’

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.