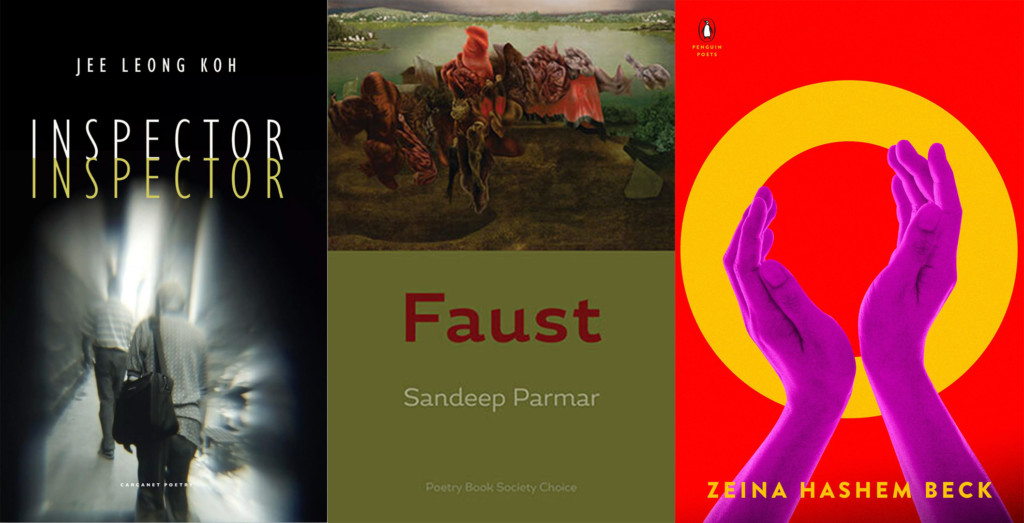

Departing significantly from his earlier collection Steep Tea, Jee Leong Koh’s latest work, Inspector Inspector, is an elegiac, yet witty and bold exploration of history, exile and Asian queer identities. Through various forms and narrative, the reader is invited into a variety of spaces: the personal or the intimate, queer spaces of the lover; the everyday for the diasporic community drawing from interviews with Singaporeans living in America; and the elegiac poems in memory of the speaker’s late father.

Central to and interspersed in this collection are thirteen palinodes drawing from what the father said during his lifetime. Spare, ironic and poignant, these are attempts to reconcile the distance between the voice and his father, the latter having never left Singapore.

I am struck by the poet’s nuanced portrayal of class and generational divides, especially in the strangeness of the intergenerational gap: the new generation’s courage and indebtedness to the elders. In ‘Palinode in the Voice of My Dead Father (VII)’, there is the comparison of how the older generation’s experience of the war has changed them and generated much resilience, as compared with the younger generation who experience the prosperous era and are better able to embrace ‘success’:

The war

accommodated

me to hardship –

[…]

as the prosperity afterwards

accommodated

you to success.

In the sequence ‘Ungovernable Bodies’, Jee explores the freedom, inhibitions and vulnerability associated with queer bodies. Drawing from intimate diary entries, these sonnets are taboo-breaking in language and form. One diary entry, tinged with humour, begins: ‘The day after sex should be a day off / for contemplation, walking in the park, / or basically doing nothing at all, /except to reunite the shattered body’ (‘Andy, July 1, 2007 (Sun)’). Such intimate, tantalising lines impose a narrative for sexual politics that dares the reader to examine, up close, the intensity of queer love and bodies, against the backdrop of everyday life and surprise encounters.

Through a section of poems derived from interviews, we also encounter the diasporic Singaporean-American community and the trauma of racism in everyday life. In ‘The Muslim’, for example, the poet challenges the unfair stereotypes and disrespect that can occur between different ethnic minorities, through a shocking scene in which a Muslim woman is stereotyped (and the public practice of Islamic religious acts are criticized) by another woman of colour, who assumes an air of superiority as she speaks on behalf of the people in America:

She was at Trader Joe’s and kneeling down

for Zini’s vitamins on the bottom shelf

when a Black woman cried in a loud voice,

‘Why are you praying here? Stop your praying.

This is America.’

The incident intimates a deeper rooted frustration with the elision of identities under the term ‘ethnic minorities’, and the slighted nuances within such categorical approaches.

The collection goes on to interrogate prejudice beyond race and faith – drawing from the life of Kopin Tan, ‘The Columnist’ depicts the first gay columnist for Barron’s and his shock when friends and social media followers decide that they ‘liked his cheesecake photos well enough’ but turn away from photos of his husband on Facebook.

At the end of the collection, we arrive at a courageous voice that believes ‘a letter is not an eulogy’ and affirms a rootedness and sense of kinship, despite the everyday trauma of rejection and ambivalence:

I’m seized by a wild desire to swear

that before every poetry reading, I’ll say,

I’m Koh Jee Leong, the son of Koh Dut Say,

in the manner of the Malays and the Scots.(‘The Reply’)

Mapping the queer migrant’s experiences, hopes and fears across a matrix of love, family history and community, Inspector Inspector offers a nuanced, politically-engaged and experimental approach towards grappling with racial history, justice and the complexity of queer body politics.

In Sandeep Parmar’s Faust, truth is composite and changeable. Weaving migration, history, and the racial imaginary, this experimental collection of poems and lyric essays draws from the reimagining of Goethe’s popular, canonical work Faust, revisited in the eyes of a migrant of colour who navigates the reverberating impact of postcolonial history.

Throughout, meaning is continuously in flux and questioned. Metaphors, fragments, spacing and a panoply of voices fuse to create a sense of displacement and longing, as the poems interrogate the problems of history in a circulatory manner. In section I, ‘Faust’, part v., ‘home’ captures nostalgia yet reminds us of the traumatic experience of racism:

Go home then–Why did you come here

To study (you tell the officer)

To retrace my steps part way home

Across a burning field

To stand in the smoke and to locate its source

and in part ix., we are presented with the collective ‘we’:

Who will we become

across several oceans–Arabian to Pacific–

rude stars

in an arc bending over Kyiv, Belarus, Astrakhan.

These lines suggest a transnational, collective identity that is subject to change and resists stereotypes. To spotlight this, Parmar utilises metaphor to weigh down the often romanticised, yet ‘rude’ in this instance, ‘stars’ – a rude realisation for the voice, as the identity they fantasise about becoming, figuratively drops down to earth.

Shifting between depictions of hunger and harvest, between personal and collective acts, the sequence of poems in section I is filled with a sense of urgency as the dramatic tragedy of the original legend of Faust is reimagined and translated into an abstract yet universal language of suffering in part xiv.:

The plough carves fate into flames that split your skull forty-six years after your birth. The douleur, the gham, the tragedy of six harvests overseen as the tumours weave like fire in your gut and the seventh, final crop you will never see breathes gently under the frost of Punjab.

The line shifts from douleur (French word for pain or distress), gham (meaning sadness in Punjabi) to the ‘frost of Punjab’, such that the hunger and tragedy is not just that of the individual’s but rather that of a much wider society. Similarly, the collection expands and contracts through the collective and individual experience…

At the core of the collection are prose poems which challenge the linearity of intellectual and racial identities. ‘An Uncommon Language’ pulls apart the complex and interior nature of grief around a miscarriage, and it ends with an elegy that acknowledges the ghost of a stillborn while the ‘[t]axonomies of grief elude the non-mother / the un-mothered, the anything-but-of-this-fact.’

As ‘far away’ cities become ‘the city […] in your living room’, the lyric voice tries to reconcile and hold together the disparate images, characterisations and meanings of the events it carries as it passes through these spaces; ‘This is not your city’ … ‘This is not your history’ (‘The Nineties’). Knowing that it is impossible, the speaker is nonetheless conscious of the universality of any feeling or attachment: ‘The cheapness of all you are obliged to call home. This is not personal.’ In pursuit of the larger meaning or purpose for exile, ‘Something Particular’ strikes me as a poem that crystallises the humanity in that longing and kinship, even if it remains elusive:

I draw a black dot under your ear every morning to ward off evil and praise. This means nothing or something particular to her.

This Indian superstition to ward off evil is a subtle, yet powerful, symbol to suggest cultural inheritance.

Bold, dramatic and inventive, Faust draws parallels between history and the present. Rich in its intertextual references, experimental use of form and language, the book demands from the reader the willingness to question or decode the meaning of one’s mosaic of experience and sense of place.

Lebanese poet Zeina Hashem Beck’s long-awaited collection, O, is a stunning collection that explores love, history, politics through the lens of a bilingual migrant. Weaving duets of English and Arabic into dialogue with the divine, these poems articulate the value and contradictions of motherhood, family and mortality.

Through strikingly original use of forms and voices, Beck’s poetry is full of yearning, vision and compassion. For example, in ‘There, There, Grieving’, the poet reflects on the forms and rituals of prayer in bringing together the living and the dead, capturing grief over so many things, from ‘a dead bird, bathed in broken light / like a little christ’ to ‘a tin of olive oil in its wooden coffin / so the airport security would let me through’. In ‘daily’, which starts with the line ‘my little country is not enough’, the speaker laments – in between lines written in Arabic – that there is ‘no remedy but / antidepressants & prayer’. In the daily ritual of loss, the speaker’s voice is filled with nostalgia and longing, beckoning others to ‘follow the lemon & minefields / follow the wailing of the ambulance / follow the songs of the dead & the living’. Although the exact nature of absence or loss is unnamed, the pain is felt deeply between the lines, amplified by the fact that the semantic meaning of the Arabic words woven into the text remain inaccessible to the reader unless they know that language, and vice versa for the English words, creating mediated access to the full meaning of the narrative.

Beck is also wonderfully talented in capturing the intersection between the personal and collective, or the relationship between one’s inner monologue and the external reality. For instance, in ‘triptych: you & my country & i’, the fragmented narrative offers glimpses of longing, bodily responses, domestic or intimate spaces, reflections on language. Even though each column of narrative reads differently, they all arrive at the same conclusion: ‘aren’t they beautiful’, which gives hope and affirmation to life as one struggles daily to reconcile with language and truth.

There are several poems that explore childbirth, motherhood, and a woman’s kinship with her mother and grandmothers. In ‘Ghazal: My Daughter’, the repetition, or radif, of ‘my daughter’ on the end of each second line holds the poem together both formally and conceptually, while the deliberate use of clinical vocabulary elsewhere deepens one’s sense of the bodily trauma the mother goes through in birthing:

When the gyno cut, I was full of god & nausea. Quickly they pulled

you out of me & the room. Said my uterus was drought, my daughter.

The first few hours your alveoli expanded, did not collapse.

I fell asleep, woke up breathless, knew what that was about, my daughter.

Two doses of surfactant & a central IV. O but your eyes:

how you breathed with them, my tiny, my defiant, my stout, my daughter.

In essence, Beck gives the ancient form of ghazal a contemporary spin, using it to engage with ideas of legacy both on the political (birthing of the ghazal) and the personal (birthing of the daughter) front. The poem forgoes linguistic expectation in its employment of clinical syntax, while still adhering to the traditional, intricate rhyme scheme and the use of the more intimate radif, expanding the meaning of loss contained in the ghazal.

Evocative and fascinating in its varied use of form, language and voices, Beck’s collection portrays with such craft and complexity one’s inhabited joys, memories and sorrows in life. It traces the daily witnessing of history, love and suffering, offering clarity to the world we are living in.

*

You can order the books via the below links:

*

Jennifer Wong is the author of several collections including Letters Home (Nine Arches Press, 2020). She is the co-editor of Where Else: An International Hong Kong Poetry Anthology (Verve Poetry Press 2023) and the author of Identity, Home and Writing Elsewhere in Contemporary Chinese Diaspora Poetry (Bloomsbury Academic, 2023). She also translates and reviews poetry. She has taught creative writing in Poetry School and other places. She is working on her next collection.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.