Ekphrasis is one of those poemy words poets assume everyone knows, like villanelle, and pantoum; but my Mac doesn’t recognise it, flags it up, and takes me to Wiki – ‘an ekphrastic poem is a poem inspired or stimulated by a work of art’. I remember feeling so happy when I first discovered the word, because it described something already I did – and there’s nothing like a Greek term to validate your practice.

Ekphrastic poetry can be transcendent and sparky, but it can also be dreary as hell, and some of the rottenest comes about, I think, when the poet fails to bring anything new; either writing a fan letter to the artwork and leaving the reader out of the loop, or assuming that by simply name-checking it, they will manifest the same effect the original art evoked. I once wrote a novel about grief, where grieving characters mooched around London art galleries pondering over artworks about grieving. I’ll admit, it wasn’t the most sophisticated way of showing, not telling, and any grieving readers looking for catharsis would have been better served visiting Richard Wilson’s sleek black reservoirs of sump oil at the Saatchi Gallery, or contemplating Rachel Whiteread’s negative spaces for themselves. In a novel, I just about got away with it, but as poets, we need to make something from our response to an artwork – to transform it for our reader. In the course I’m running for Poetry School in July, I hope to share some of the ways we can take our inspiration from an artwork and use it to write – and especially to write about self representation.

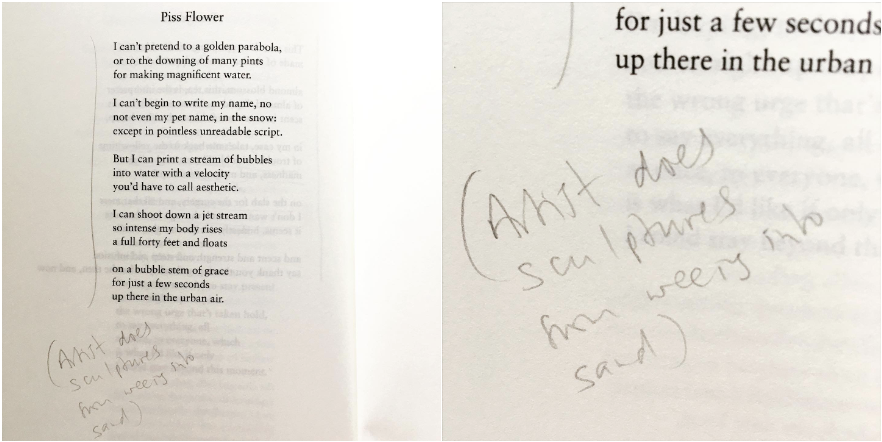

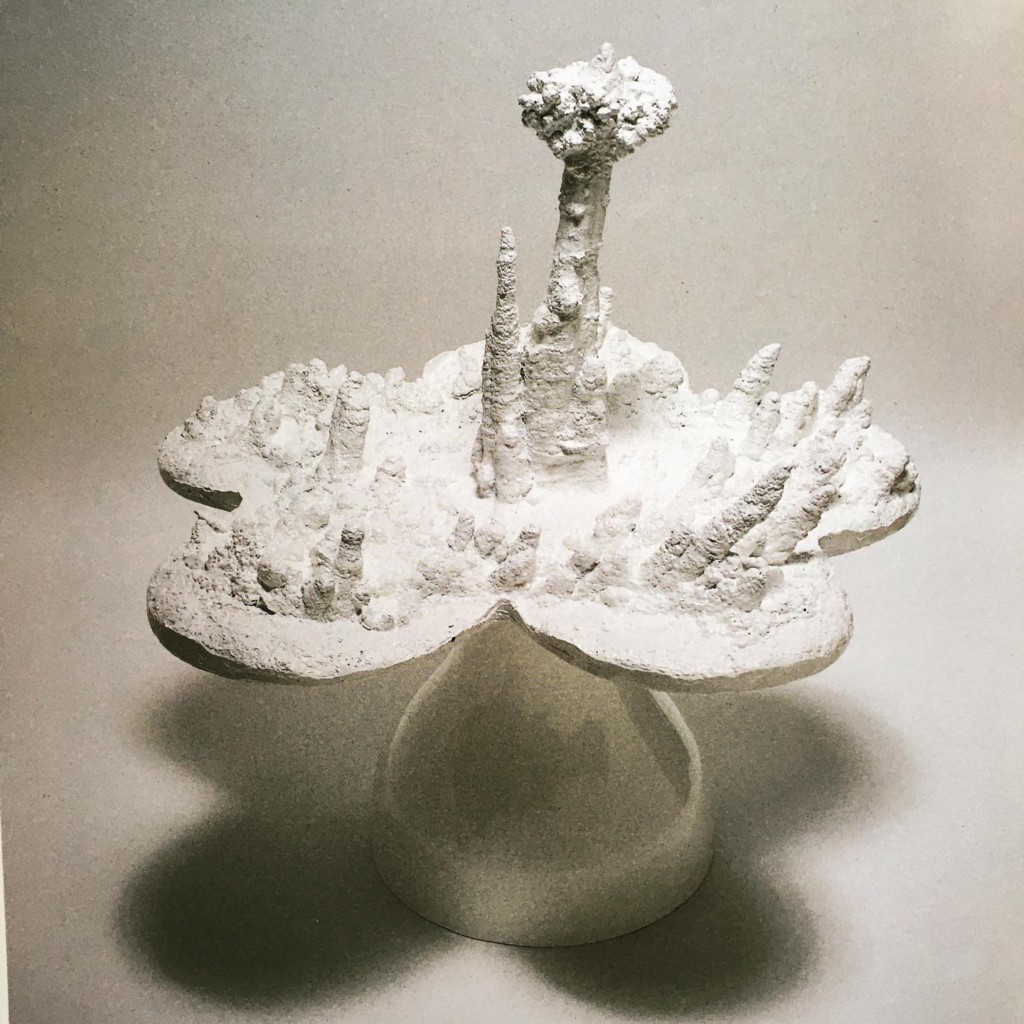

I’ve called the course Of Mutability – a title taken from Jo Shapcott’s collection (Faber, 2011), which itself came from Helen Chadwick’s multimedia artwork (1986). Shapcott draws inspiration from a selection of Chadwick’s work, and it’s a rich seam. But does it matter if the reader doesn’t know the works? A few weeks ago, I came across Shapcott’s book in my local Oxfam. Pencilled in the margin of one of the Chadwick-inspired poems, Piss Flower, I found the note: ‘artist does sculptures from weeing into sand’, referring to the fact that Chadwick created the series of sculptures from impressions made by pissing in snow (who knows how this became sand in the reader’s note). Does Shapcott make something new out of her response to Chadwick’s work? I think so, absolutely. Do we need to know the original artwork to appreciate the poem? I’d say not, but then, I know the work, and so can’t un-know it. But maybe the reader who gave their copy to Oxfam felt left behind. It’s definitely something we’ll be considering during the course, as we explore making ekphrastic poetry that resonates with our experiences, and then, hopefully, resonates again for our readers.

Book here for Claire Collison’s course ‘Of Mutability: Ekphrasis & the Body‘, running as part of our Summer Term 2022.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.