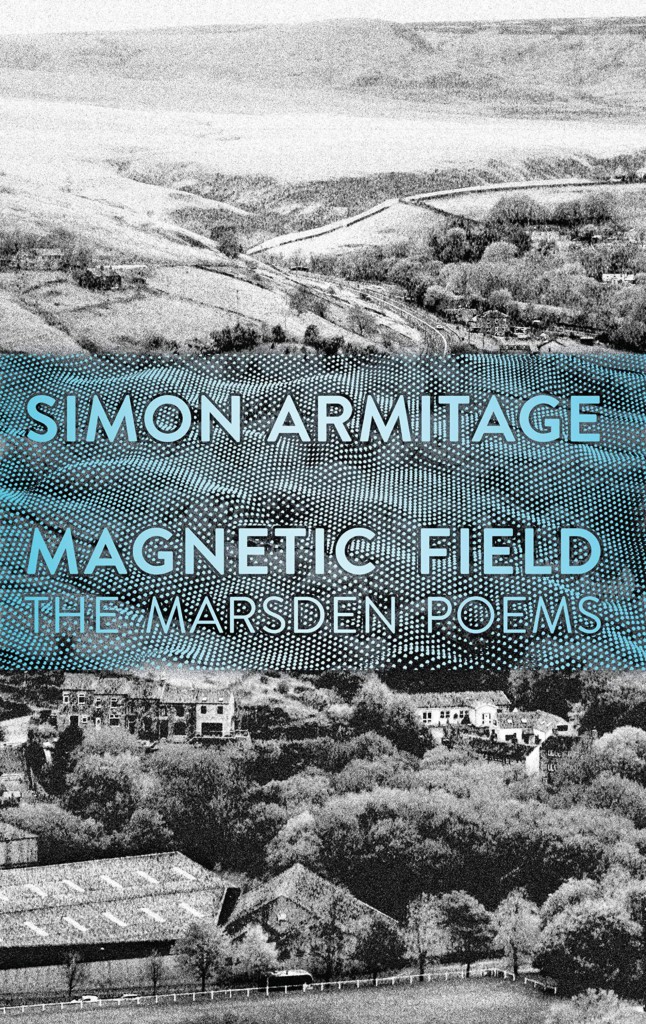

Simon Armitage first referenced Marsden, West Yorkshire, in his inaugural collection Zoom! (1989). Over 30 years later, with Magnetic Field: The Marsden Poems, we’re taken there once again. The poems are like cardinal directions, pointing back to the landscape and inviting readers to gather in a geographical amphitheatre.

As with many poets, the childhood home offers a creative wellspring: bricks and mortar provide the structure; dripping taps the punctuation; doorways ellipses to the world beyond. For Armitage, it’s not only a house, but an entire village that swells with inspiration and nuanced information. Roman roads, open moors, terraced houses, and playgrounds are part of a universe in perpetual motion:

Forget

(‘The Catch’)

the long, smouldering

afternoon. It is

this moment

when the ball scoots

off the edge

of the bat; upwards,

backwards, falling

seemingly

beyond him

yet he reaches

and picks it

out

of its loop

like

an apple

from a branch,

the first of the season.

Though the collection spans eighty-nine pages, fifteen black and white photographs, numerous locations and a plethora of experiences, all the poems can be credited – to some degree – to the confines of a bedroom window. Through the glass pane, Armitage would often look down at the streets below, observing and internalising the mechanisms of village life:

The frame of the window might have operated as a limiting device, restricting my perception of the wider world, but it was an invaluable template for bringing focus to the poems and legitimising the use of local subjects and vernacular in a poetic context.

(Introduction, p.xi)

This concept recurs. In ‘Kitchen Window’, a pane is replaced to satisfy the desire for ‘more view, more day’, and with it, a whole new microcosm of possibilities. It provides a portal to a new kind of life:

Wrapped in a canvas sheet the brand new pane

rode on the side-neck of the joiner’s van.

Undressed and carried, cloudscapes tilted

in its mirror and the planet swayed, though

set in place it seemed a solid nothingness –

a panel of air or frozen light

that magnified its own transparency.

The poem is one of many which depicts household events with a ‘near-sacramental pattern and process’. Through the glass, the speaker reflects on their place within the universe as well as the vulnerability of such a position. The piece is palpable and celestial – balancing the quotidian with the experiential – as it assesses the enormity of outside possibilities.

This sense of introspection is taken further still, deftly anthropomorphising the window and its lifetime within the household. The old pane, with its ‘dulled soft-focus cataracts’, is wilfully ‘thrown in the skip’. The home is an extension of the body – with memories built into the blueprints – subject to ageing, decay, and the removal of certain parts.

Armitage glances sideways to a fearsome periphery: the inevitability of outside dangers or, perhaps darker still, of simply moving on. This existential melancholy creeps into view on many occasions. In ‘Camera Obscura’, an omniscient narrator describes a mother in the distance, who grows smaller as she moves out of her son’s view:

On Old Mount Road the nearer she gets

the smaller she shrinks, till he reached out

to carry her home on the flat of his hand

or his fingertip, and she doesn’t exist.

As is customary for Armitage, this collection is intrinsically performative. The acts of living, seeing, and understanding are inherently bound to the paths we follow. This is true of the lines across the page and the landscape in front of us; the journeys are tightly aligned for both the poet and the reader.

‘Privet’ exemplifies this succinctly and with sophistication. A young speaker describes the task of cutting a hedge as penance, cutting a clear line across the boundary of his household. Whilst making amends for an unknown deed, the narrator opens up the idea of borders — geographical, anthropological, and cultural:

And because I’d done wrong I was sent

to the end of the garden to cut the hedge,

that dividing line between moor and lawn

gone haywire that summer, all stem and stalk

where there should have been contour and form.

The words sit between childhood and adulthood. They consider the thin lines between decision making, consciousness, and accountability. The poem also hints at the intersecting topography of Marsden: where Yorkshire meets Lancashire. The village is in many ways a utopia beyond definition – sitting outside of reality – but it is also a linchpin for the speaker’s fragile and rapidly forming identity:

and I floated there, cushioned and buoyed

by a million matchwood fingertips,

held by nothing but needling spokes and spikes,

released to the universe, buried in sky.

Like a needle in a compass, Armitage continues to align himself with Marsden as a place of ‘recalibration’ and ‘poetic measurement’. In a time of lockdown, these poems offer an opportunity to engage in a ‘fascination with everyday domestic detail’. Magnetic Field is a complex and alluring interpretation of our connection to both interior and exterior spaces: the grass is near touchable; the evening breeze tangible; the ‘horizon ablaze’ (‘Emergency’). The fields await our return.

Kate Simpson is Associate Editor at Aesthetica Magazine, and Editor at Large for Valley Press. She has had both critical and creative work published in The London Magazine, The Poetry Review and Mslexia, amongst others.

Magnetic Field by Simon Armitage (Faber & Faber)

I grew up at Crosland Moor just down the road from Simon and remember trying to walk there when I was about seven and looking down on the village from the moors above at sunset. I don’t know why I was drawn there but Marsden seemed set in its own time zone, very different from the pebble dashed council estate where I grew up. These poems reflect Huddersfield which is a place of odd perspectives with villages clambering up strange angles and more particularly for me the strange separateness of Marsden.