‘Fondue’ must be one of the more descriptive words in the language. It summons up consistency, texture, a sense of movement, taste and smell. Even the sound of the word is evocative: the onomatopoeic glooping of ue – and borrowed from French, too. It’s certainly more suggestive than ‘melt’.

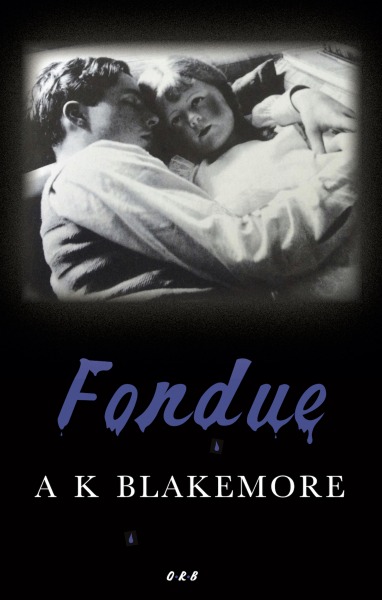

It’s an appropriate title for this new collection, as A. K. Blakemore has a particular gift for such succinct description. Poetry can be many things, but Blakemore’s work proves again one of its simpler definitions – ‘the best words, in the best order’ – though, as we will see, Blakemore’s politics are far from Coleridge’s conservatism.

Take the poem ‘grandmother’s cat’:

my grandmother’s cat is ugly

because he’s always been that way:

the woollen wrists,

scapolite eye unhooked

in quasi-mystical disputation –

but he is also beautiful and this because i hold him

in very high esteem.

I don’t know what scapolite is, on first reading, but it does not matter. The point is not only the image the word suggests to me, but its technical precision as description. It is evidently a word specific to science, implying that a scientifically exact approach to classification is required – more so than accessibility for the reader – to the extent that even the cluster of consonants seem to curtail the lines, making them sound exactly measured. This microscopic attention, across several registers (both the unfamiliar ‘scapolite’ and more homely ‘woollen’), shows a level of attention that indicates respect. The lesser regard shown for the reader, here, is inverse to the attention given to the cat.

In fact, throughout the collection, none of Blakemore’s descriptions are predictable. Later, in ‘Fountayn Road’, there is a body with ‘gums mauve / like a brachycephalic puppy’s.’ The unwieldy ‘brachycephalic’ delays the end of the line to a comical extent, signalling its own reluctance to reveal itself easily. Look the word up, if you want; you know you can easily do so on your phone, and so do the poems. Usually, similes perform a kind of logical clarification; at the beginning of Bleak House we know how much mud there is in the streets from Dickens’ helpful comment: ‘as much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth’, which draws on a common fund of images. Yet in Blakemore’s poem, the similes tease the reader, actually going deeper into opacity.

As Sam Riviere said about Blakemore’s first collection, Humbert Summer, the poems ‘don’t care about you’. The same is true of the poems in Fondue, but don’t let that dissuade you from reading them; both Humbert Summer and Fondue take joy in consciousness of language and lyricism. They are not just about precise description. However, Fondue has a harder, darker message than Blakemore’s earlier work. Violence – anonymised, sexual – is a threat threading through the collection in poems such as ‘golem’, ‘samaritans’, ‘lovers’ and ‘bedspread’, which put pain and power relations at the centre of a relationship. This is most explicit in ‘lovers’, especially its final line:

i was frustrated by

the way he received fellatio.

that very blonde underarm –

with the passivity

of a teddy bear of a dog –

how

(tight-clasping memory!)

no one was allowed to hurt him

but me.

Punning on sadomasochism and a duller, mental kind of pain, Blakemore makes the point that hurting each other is what ‘lovers’ do. Doubling and linking these two types of pain, she interrogates the concept of pain itself, challenging us to consider in which cases pain – of any kind – is asked for; is even pleasurable. Earlier in the poem, the image of a male partner as a ‘blonde’, ‘passiv[e]’ ‘teddy bear of a dog’ reverses conventional stereotypes of masculinity. Yet the point is not that a feminine male partner is particularly transgressive (we do not know the speaker’s gender, anyway). In context, it is in the way that love is represented in terms of passivity and frustration, giving and receiving, hurting and being hurt – the tense binaries that make up a relationship.

There are also poems in here that are unassuming, tender, and uncynical. But these moments are felt precisely for being on a knife-edge; a sense of threat is realised through skilful use of temporality. In ‘February 13th’, which begins with an exuberant simile:

love is … slowed down

like an ice-dancing championship replay –

The poem turns in the central line:

this is the moment i feel i have lost you –

Love’s events are pinned to days and moments, creating the uneasy sense of a world in which everything beloved can vanish without warning.

The sense of transience is also emphasised in the poems’ length. The short, vivid, haiku-like poems of Humbert Summer were sometimes played for laughs (I recommend ‘Ross and Rachel as invertebrates’). Short poems can run the risk of sounding like Instagram Sappho-lite or bad stand-up, but the shorter poems in Fondue are more complex, playing with restraint and voice in the space of time it takes to read them.

‘amateur’ is an unsettling shorter poem which uses its brevity as its effect. Beginning with dramatic irony, with the reader and speaker as complicit eavesdroppers, the power of knowledge is concisely reversed:

to listen

to their conversation

i became a blue silk fan

spread high on the wall

of the chinese restaurant –

& then

the same beneath him.

End. From being ‘high on the wall’, our perspective shifts abruptly to the opposite point of view, ‘beneath him’. From the speaker clearly explaining exactly where we are and why (‘to listen’), this abrupt shift is left unexplained: it is confusing, and feels all the more sudden due to the zeugmatic use of the verb ‘spread’, which Blakemore uses once to locate us in one place, then, without wasting time on repetition, in another – it is concise to the point of leaving us feeling dizzied.

Despite its brevity, there is much suggested in this poem – the ‘chinese restaurant’ could be the usual high-street takeaway, but the ‘blue silk’ bears an extra glamour and suggestion of luxury – why is the speaker here? The implied voyeurism and sex in this poem suggest further uneasy questions: who is the anonymous ‘he’? Has the speaker been caught and sexually trapped ‘beneath him’, or are they using their sexuality in order to continue spying? These are questions suggested but left unanswered: at the end of the poem, the fan is physically held down and the voice curtly cut off at ‘beneath him’ The poem leads us in, but then uses its own length to hold back meaning and create an unsettling effect.

Throughout this collection, those silenced struggle against silence. The voice of the poem against the unnamed them, against the ‘surface […] suitable / for the breaking / of horses, and myself’, the pain lovers cause each other, the recurrent, encroaching darkness that serves as counterforce or backdrop to the tenderness in these poems. Ultimately, there is an imbalance; the underlying threat of violence means that, for all the moments of bright beauty, these poems reflect a world of fear and threat. This is the fault of the world rather than the poems, but makes Fondue at best, ironic, and at worst, bleak.

All the more heartening, then, to find two final poems blazing up in empowering fury. ‘golem’ and ‘beau’ are poems about remaking the world for yourself. ‘golem’ explicitly tackles the issue of enforced silencing: ‘Cleopatra was a cunt for going quietly –’ enacting its refusal through the speech act that is the poem itself, and emphasising this with three curse words in the first two lines:

you tell them not to fuck with you but they’ll fuck

with you anyway maybe even fuck you if they can

‘Fuck’ and ‘cunt’ are taboos, spells, language that has violent effect simply through being spoken. More joyful is the very last poem in the book, ‘beau’, which remakes another male-centred literary myth; that of the observant savant flâneur. It is usually a male – Baudelaire or Rimbaud or Iain Sinclair – who chronicles life from the street. Blakemore plays with this assumption by suggesting in the final lines that the speaker may not be male:

oh how

i feel like god and endlessly –

will there still be waterside places people go to die happy?

will they say i was a

lonely seer, a savant, a lover of men?

The question is unanswered, but in conjunction with other poems that interrogate treatment of the female body and its sexuality, there is a suggestion that this is a female voice. After Fondue’s confronting, exposing and ironising social treatment of the body, ‘beau’ is uplifting. With the recent increase in visibility of street harassment, female walking has become politicised (though, for women, at night, it always was); with this in mind, the suggestion that the speaker is not the default male-as-norm, when made so lightly, feels freeing.

You can find out more about Fondue from Offord Road Books.

You can find out more about Fondue from Offord Road Books.

If you’d like to review for us or submit your publication for review, please contact Ali Lewis on [email protected] or Will Barrett on will@poetryschool.com

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.