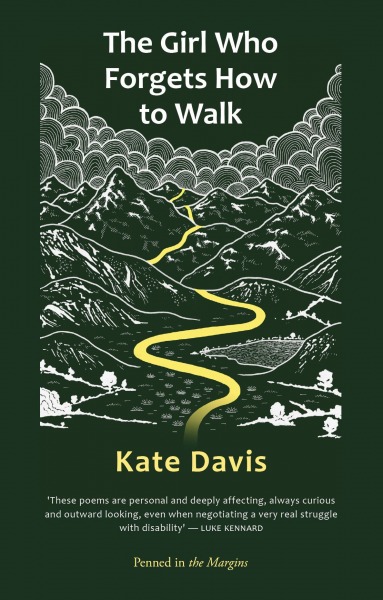

A personal quest to re-learn how to walk through cherished, northern landscapes introduces a gifted new voice. Gathering fragments from memory, myth, archaeology and geology, Kate Davis’s debut is a nimble exploration of what it means not only to exist, but to persist.

The Girl Who Forgets How to Walk feels to me incredibly timely. Coming on the back of a surge of so-called ‘new nature’ writing, Davis’s perspective – female, middle-aged, disabled – is refreshing. In what has become de rigueur, a (usually white, male, able-bodied) narrator will be inspired to set off following some river or shoreline, tracing Situationist ambiance onto the terrain in order to offer mild critique of late capitalist ennui. Thankfully, Davis’s book shuns what we might term ‘common denominator psychogeography’ to present the reader with something altogether more fulsome.

Split across three sections, The Girl Who Forgets How to Walk is a sustained rumination on how we come to terms with disability and loss. It is also a book charting the wildness of Cumbria and Lancashire and how we, as human actors, figure in the landscape irrespective of our flaws. ‘When they say geology, she sees anatomy’, Davis writes in ‘She examines her fear that the ground is not to be trusted…’, one of a series of poems which has a self-reflexive narrator ruminate on the circumstances that led to her forgetting how to walk.

Most impressive about the book is the way that, to use a term of Davis’s, nearly all of the poems ‘channel’ back to the half-forgotten circumstances that led to her contracting polio from, it would seem, ‘the boating pool brimming green’. In ‘How the forgetting began’, this knowledge is nebulous, not absolute:

The thing she didn’t know —

the sea hid a gob of virus

.

Things she knew —

the waves’ hard slap on the fleet of little peeling hulls

the shocking intransigence of small boats

.

The thing she didn’t know —

the virus intended to get to the core of her spine

Not to know that ‘the virus in her spine would bring a terrible dream of heat’, such a lack of omniscience is immediately countered in the following poem, ‘The hot, terrible dream’, in which a fragmented narrative uses the run-on line to deft effect, channelling the refracted memories of care and convalescence.

The opening sixteen poems in the book are the most off-kilter, but that is not to say misplaced. On the contrary, Davis’s decision to include adaptations of geology texts (‘Limestone (CaCO³)’) and chemical formulas (‘Sinkhole’) between a ballad warning of ‘Ginny Green Teeth’ (‘Grim’) and a modern sonnet set ‘ten feet above the rubble’ (‘Relativity’), shows how dexterous a writer she is, how capably she plays with form, and how committed she is to investigating her subject from many, often-obtuse angles. In this sense, opening poem ‘Peninsula’ is a masterstroke:

We never speak of it, but here we know the land

cannot be trusted. So a woman

might reach out her hand

towards a rail in Debenhams

and for a fraction of a second

knows the earth beneath the town

is shifting as limestone lays itself open to rain

Interested in scale and the playing-off of everyday objects of modernity against glacial time, the poem, with its clever ear for internal rhyme, seems to be measuring the personal against the prehistoric (the ‘Costa […] mocha’ against the ‘Permo-Triasic rocks’). The last poem in this introductory section, ‘Disaster’, sees Davis toying with line lengths, foregoing a conventional account of a train crash which ‘everyone remembered’ to instead focus on the surreal image of the ‘whole train falling slowly’ into a sinkhole. I have not copied verbatim Davis’s use of line and even word breaks here, but it should be noted that their cumulative effect makes for a kind of stalling: the blunt terror of a one-hundred foot chasm opening in the earth and swallowing a carriage full of people is apprehended. Are we – is our narrator – certain that this disaster actually happened?

Two preceding poems would have us be sceptical. We begin to wonder if it is animism – the ‘troll teeth’ in the ‘mouth’ of the pit in ‘Limekiln’ – or myth and folklore – the ‘stories of farmers’ in ‘Haematite’ – which is at fault here, but then Davis seems more intent on the bigger picture: might both be different sides of the same coin? The fallibility of memory and the impermanence of apparently-solid elemental structures are routinely clashed together.

By the time we reach its closing section, images and motifs have begun reappearing. While this forms a pleasing narrative arc – this is one of few collections which I’ve felt obliged to read in order – it also makes for thematic unity; some order amid the chaos of circumstance. ‘The Taxidermist’s Apprentice Discovers Palaeontology’ sees the return of the pink dress in ‘Peninsula’, while ‘gigantic bones’ and ‘jelly-fish in a warm viscous sea,/tree-ferns decaying to sediment’ remind the reader of the cornucopia of ‘certain creatures’ met elsewhere in the collection (‘Bodies’).

In poems which convey the lyric heft of ‘clouds that were […] ideas about colours you’d wear to a summer dance’, to phonetic trials in relearned perambulation (‘She teaches herself to walk across a limestone landscape’), Davis’s bold cartography places her firmly in literary territory of her own, following the ‘pathways of the ancestors […] for something to hold on to’ while shaking the ground beneath the reader’s feet. Ultimately, The Girl Who Forgets How to Walk is a map and compass for uncomfortable terrain and self-doubt. Nowhere is this more distilled than in ‘Boulder Drift’, whose title puns on being more assertive:

She would have preferred the one

geologists gave it — Boulder Drift.

To imagine those stones suspended,

.

all weight gone, their pock-marked bodies

lifted and held like dancers. To think

of drifting — a sugar-stealy blown

from weeds, weightless, the iron-work

gone from her body. To think too

of being bolder, braver —

You can find out more about The Girl Who Forgets How To Walk from Penned in the Margins.

You can find out more about The Girl Who Forgets How To Walk from Penned in the Margins.

If you’d like to review for us or submit your publication for review, please contact Ali Lewis on [email protected] or Will Barrett on [email protected]

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.