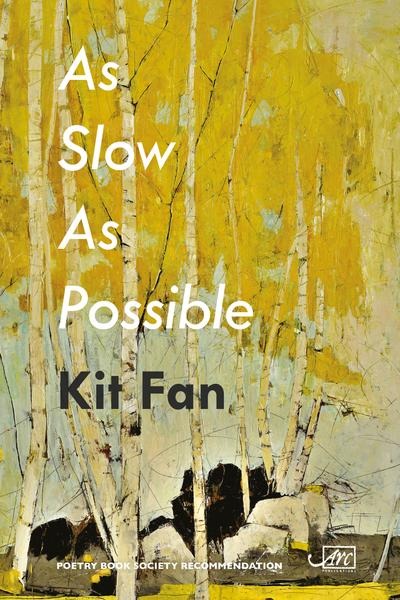

Kit Fan’s multifarious second collection takes its title from an art installation / piece of music for a church organ by John Cage which began its performance in September 2001 and is scheduled to end, believe it or not, in 2640.

It takes on average over a year for a note in Cage’s composition to change. While reading Fan’s latest collection does not require such an investment of time, his title poem attempts to help us savour our time on earth, to slow us down and how the way we rush about our diurnal lives is often at loggerheads with such art. While other poems in the collection, such as ‘Banksy in Gaza’, suggest that art is a decadent thing that intrudes on issues that it cannot resolve (‘how should we unimagine a thing once it’s been imagined?’), there is a prevailing sense that the poet believes poetry and art will prevail. We:

will gather in the right transept, first to listen

to that last note sustained by sandbags on pedals,

its ghostly, peculiar ring in the ear reminding us

of ourselves; then, if breath can still be held,

to witness the sandbags being gently removed

all at once, so that this time, we can hear the finished

sound, the tinnitus recalling absence.

It is something of a memento mori of a poem, as the speaker knows perfectly well that not a single person alive today will survive to hear and witness the end of this piece. By 2640, the language of the poem might have been completely superseded, it might be a dead language, worse still, humans might have died out and the earth might not even exist. Many other poems in the collection certainly suggest that this is a distinct possibility, such as ‘Spill’ which imagines the seas of the earth engulfed in a giant oil spill.

But Fan is no harbinger of doom – we are all to die and Fan attunes this to a gospel of love, desire and unity. As an acolyte of the poetry of Thom Gunn (on whose poetry Fan did a PhD at York) he is particularly strong at capturing a sense of the earthly sanctity of lovers and lovemaking. This awareness of mortality brings Fan’s poetry into poignant focus, as in ‘Transmigration’:

The day we saw a kingfisher on the Roman bridge of Salamanca

was the day we saw two otters on the bank of Rio Tormes in Salamanca

.

[…] What would I barter for

this life? A man for a bird, or a stone for a pillow, except the thought

.

of you alive, or better still, us alive simultaneously, even once,

is enough. But just in case it’s true, let’s be the two otters.

The niggling sense that reincarnation does not exist makes the closing lines all the more affecting. At certain points, time weighs heavily in the collection, such as in ‘Duodenum’, the very title of which suggests a process of being broken down. The poem is a rather plangent portrait of the poet’s/ speaker’s father, ‘a failed man’ who seems to wither away with sadness, rather like Melville’s lowly clerk ‘Bartleby’ in a short story of the same name. Here it is love and family rituals which slowly thaws out the father and brings him back to some semblance of functioning life:

[…] He would curl up and hug his wife’s

pillow close to his chest […]

.

That was how I learned to cook: rinsing grains of tear-like

rice over a cold tap […]

I was ten, at most. In the end, he would emerge

from his cocoon, turn on the gas, throw in what seemed

a life sizzling in a wok.

At other times, Fan can take vast tracts of time and history in his stride. Note Fan’s choice of verb to describe his walk in ‘Les Alyscamps’:

We saunter

through the road of open tombs, unnamed

by their weathered stones. Here a trace of Adam hiding

in the leaves and there a firstborn dangling

from a sword. Christ was here once, attending a funeral.

Temporality and Christianity are central threads running through the collection and they are both tacitly evoked in ‘Migrant’. Not only does this poem pick up on the idea of Fan as a widely travelled poet, with a vitally transnational outlook, but its setting, Russell Square, brings to mind TS Eliot who served as an editor for many years in the Faber and Faber offices on the square. Both Eliot and Fan share a fascination with the passage of time and of the aesthetics and icons of Christianity, and Eliot’s ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ carries that well-known refrain ‘there will be time’ and his literary criticism (‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’) was all about finding ‘belatedness’ in texts – that is, how texts are echoes of older texts, haunted by dead poets and writers. In ‘Migrant’ Fan suggests that not only are we all immigrants from one place or another, but we are also travellers through time whether we like it nor not. Fan sees not only the environment being at risk but also human frailty, and the need to cherish the moment:

We all have it, living it, re-living it, shaping this one-off malleable

thing over and over that even though all winter we’ve seen

what could happen to it, we still sit on the bench among the perishable

green, chattering about it as if it won’t leave us just like that.

In case my comparison with Eliot is thought too conjectural, it is clear that Fan embraces Eliot’s undeniable influence elsewhere in this collection, in a poem such as ‘Doublespeak’ with its clear echoes of the opening of The Waste Land:

Early April, some greening syllables

are jostling their way through

the drizzly soil.

It is also interesting to note that in the sequence ‘Twelve Months’, a poetic calendar, Fan reports on the death of a female factory worker from asbestos exposure in the early 1920s, at the very high-tide watermark of literary Modernism. It is the ordinary, enchorial voices of workers in the streets and in the pubs that populate Eliot’s poems, and so too here does Fan take into account those so often overlooked in poetry and by doing so, grounds and earths his work in an accessible and relatable realm.

Like the title poem and work, As Slow As Possible accepts that our lives are circumscribed little pockets, or ‘spots’, of time and the task of the poet is to try and slow us down and notice the magic in the everyday that we take for granted, or are too busy to take in. This is a highly eclectic collection of poems, amply demonstrating both the conceptual and technical range of Fan’s poetry, as well as his intellectual and intertextual verve. As such it would be wrong to leave any review of this collection without even a passing mention to the ambitious long poem ‘Genesis’. In a collection tempered with an atmosphere of fugit inreparabile tempus and of mortality, it is refreshing that the collection in its second half delves into beginnings and births. This poem uses the forbidding language of the Old Testament to present Chinese creation myths and it has to be said that what Fan achieves here is something boldly phenomenological, where neither culture is submitting to the other, where East and West exist in unison, and where people are to be found ‘in / the beginning of time and in the end / of time’.

If you’d like to review for us or submit your publication for review, please contact Ali Lewis on [email protected] or Will Barrett on [email protected]

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.