In a recent reading, Eve Ewing quoted the Black Liberation Army leader Assata Shakur: “Black Revolutionaries do not drop from the moon. We are created by our conditions.” Ewing agreed with Shakur, but then went on to ask: what if they did drop from the moon?

This is the premise of the opening poem of Electric Arches. In ‘Arrival Day’, the ‘moon people’ land to turn a dystopia upside down:

the girl ones were greedy and lustful and

felt no pain but made endless noise and how small ones could

trick you, looking like children but their skin was mercury

and they could not be shot dead so do not fall for it.

The moon people are the arbiters of empathy; they know the pain and come as saviours: ‘this here is christened a new thing’, they say as they smash Hennessy bottles on squad cars. ‘[re-telling]’ poems such as this use imagination, and a blend of magical realism and science fiction, as a coping mechanism; typed text gives way to handwriting to reflect an escape from reality.

In ‘four boys on Ellis’, the boys have been stopped by the police, suspected of stealing a phone. Our narrator, observing this, decides to close her eyes.

When I opened them, the police were shouting and jumping into the air, grasping at the boys’ shoelaces as they drifted up into the clear night. Their bikes went up, too, and they managed to climb atop them midair, which was impressive.

Similarly, ‘the first time [a re-telling]’ describes the speaker’s first childhood experience of racism while innocently out riding her bike. When an old lady shouts ‘go back to your nigger Jesse Jackson neighbourhood’, it is the young girl’s imagination that helps her to cope. The text turns to handwriting and the bike is able to fly. She circles the lady, making her dizzy, then scoops her up and flies with her to a lake, leaving the old lady on a rock. It is one of many cinematic moments in the collection.

Section Two of Electric Arches, ‘oil and water’ addresses the black female body. Poems like ‘Shea Butter Manifesto’ praise and take pride in black skin and that which protects it:

heal yourself, baby

with the tree and the touch, with the turmeric

In this world, nothing brittle prevails

so in this world, grease is a compliment

no, it’s a weapon.

‘One thousand and one ways to touch your own face’, meanwhile, is a beautiful depiction of a turbulent coming-of-age experience through the medium of make-up and a daughter’s love for her mother:

even now, in this room, I see her

resplendent in indigo, smelling of otherworldly things,

draped in damask before the mirror

as a wandering woman would be,

smiling from the end of a tinkerer’s cart,

toes tracing lines luxuriantly through the mud.

And in ‘Ode to Luster’s Pink Oil’ and ‘why you cannot touch my hair’ (like two others in the collection, the latter poem is in white font on a black background), hair becomes an extended metaphor:

‘my hair is a speakeasy, it’s not that no one can get in – it’s just you don’t know the password’,

In the final poem of Section Two, ‘Thursday Morning, Newbury Street’, I am reminded of the micro-aggression in Claudia Rankine’s Citizen when the therapist mistakes her black client for the cleaner. In Ewing’s poem, when seeing a child therapist, the speaker says,

I can’t afford this therapist.

He sees me for a nominal amount – so low that when he first names the number I ask to pay ten dollars more. So low it is really just a courtesy. It’s symbolic, like the city selling vacant lots for a dollar.

But, of course, the poem is also about mental health — the secrecy of it. She wonders ‘if therapists are immune to small indignities by virtue of knowing everything terrible about you.’

Section Three, ‘Letters from the Flatland’, is about place, both in the ordinary sense, as in the narrative poem ‘Chicago is a chorus of barking dogs’, and in an extended sense, going beyond a city or home to the body as it negotiates itself in an attempt to keep it all together – even by such mundane but important things as looking after your hair and skin. In ‘at the salon,’ hair recurs as a theme, this time as a conduit for imagination about place:

I see the world from here, and the world is dark brown,

and the world keeps me modest, hidden,

.

from without, I am not a face, but a lace curtain

as over a woman betrothed

as over the window of a solemn neighbor

as over a passing hearse’

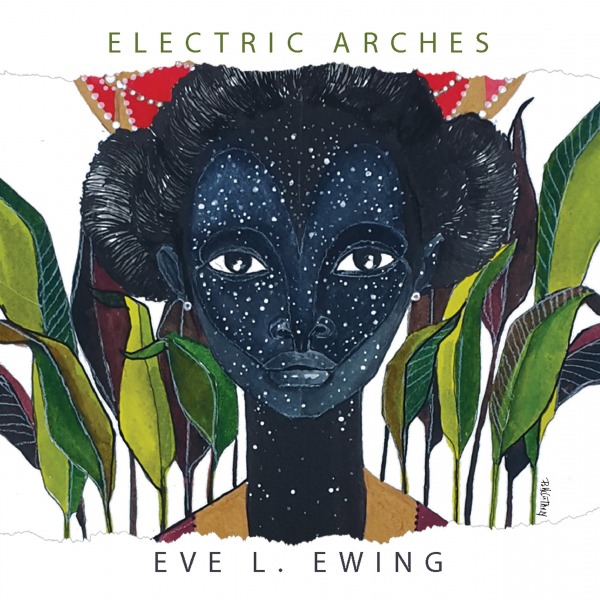

Both in the way it deals with the theme of racism, and in the forms presented – the mixture of free verse, narrative, handwriting, white font on black space, and images – this is a book of huge imagination. It is an imagination that reminds us that it is not just institutions, but people who must change. As Assata Shakur also said: “It’s not enough just to change the system. We need to change ourselves.”

And we cannot rely on people coming from the moon to do that.

Reviews are an initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at [email protected] or Ali Lewis at [email protected].

You can

You can

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.