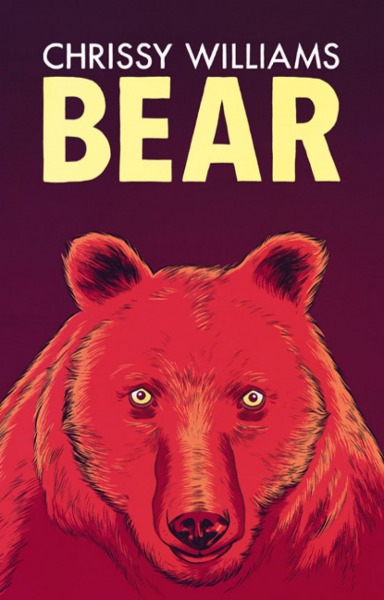

An enormous bear with piercing yellow eyes fills the cover of Chrissy Williams’ first full-length collection; stare for long enough and its neutral expression seems to shift from challenging to friendly to curious to sad, and back.

The bear appears again in the opening poem – ‘Bear of the Artist’ – cementing its symbolic significance for the poet. The speaker explains: ‘I asked the artist to draw me a heart and instead he drew a bear. / I asked him, ‘What kind of heart is this?’ and he said, ‘It’s not a / heart at all.’’ This interchange suggests that artistic expression is personal, not a matter of right or wrong. When questioned, the artist explains that he ‘[…] mistrusts anyone / who tells you they know what kind of place the heart is, the head, / how it should look, what size, what stopping distances, etc.’ Human experience is plural – interpreted, experienced and depicted in a myriad of ways. Acknowledging this ‘truth’ seems especially vital in light of uncertain world events, as the artist explains: ‘nights are getting darker, and we’re all tired, / we’re all so tired.’ In keeping with its fluid interpretation, the bear takes on a new meaning as the poem ends:

everyone could use a wild bear, though they can be dangerous

and there’s nothing worse than a bear in the face, when it breaks –

always remember how your bear breaks down

against the shore, the shore, the shore.

While a ‘wild bear’ brings a certain drive or urgency to a life, there is also comfort to be drawn from facing our fears and thereby diminishing them; this is emphasised by the soothing sibilance and repetition in the last line.

The subjective idea of ‘what kind of place the heart is’ persists throughout Bear. Many poems explore the theme of love with what feels like untempered expression; the tone is typically conversational, playfully drawing on in-jokes without elucidating matters for outsiders. With tenderness and humour, ‘Bedroom Filled With Foam’ is about disrupting a couple’s overfamiliar night-time routine:

If you want to watch something in bed, I will come and watch

something in bed with you. If you want to go straight to sleep, I

may stay up a little longer as I’m not ready to go to sleep just yet.

If, for some reason, we can’t get into the bedroom, say, because

the bedroom is filled with foam, not that I’m saying I have filled

the bedroom with foam or anything

The private mythology of references and anecdotes that exist between two people in an intimate relationship further teased out in ‘Where Have You Put the Wine,’ as the speaker attempts to locate the bottle by questioning their (possibly) inebriated partner. The answer moves from ‘the oven’ to ‘the cold oven’ before the speaker deciphers their nonsense: ‘‘You’ve put the wine in the fridge?’ / ‘I’ve put the wine in the fridge.’’ And presumably in ‘Jam Trap’, the partner likewise understands the speaker who ‘beaming like an idiot’ announces that they have ‘a brain like a jam trap.’

Williams’ writing also reveals a love of language, particularly for its capacity to move and connect us. In ‘Poem in Which I Respond to Notes Pencilled into the Margins of Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Selections’ the speaker enjoys constructing a dialogue with a book’s previous reader through their notes (‘Poems are toys and you’re right: everyone plays with them in / their own way’) and agrees with Finlay’s assertion that ‘WORDS ARE DIFFICULT / TO PUT INTO WORDS.’ In ‘Bliss’ also, the speaker has an interactive experience with Douglas Dunn’s work at a poetry festival. A scholar gives the speaker ‘Dunn’s copy of the source book / Bliss. I hold it. An old object.’ Like a shared secret, he instructs the speaker to read a hidden handwritten poem. This medium feels more intimate, seeming to preserve Dunn’s energy:

Starting slow, squinting in

at the black ink, biro I think,

handwritten loops, the bounce,

twirl, I read them, speeding up.

Propelled along by the exuberant shapes on the page (‘loops’, ‘bounce’), the speaker reaches the end of the poem suddenly, and is unexpectedly overwhelmed: ‘I see / what I did not want to see / and choke on the final stanza.’ The reason for this reaction remains private, and like other poems in Bear, this too seems to draw upon a private world of associations. Addressing an unidentified person, the speaker explains: ‘[…] I can only think / how much I want to tell you / this, how much I want / to tell you everything.’ The line breaks convey breathlessness and emotion, demonstrating the power of words to unlock personal experience.

Experiences with paper and pen contrast with Williams’ poems on communicating in the digital age. ‘Digital Ghost Towns’ laments the internet’s dead links in an outpouring – without pause or punctuation – that describes a place ‘full of dead ends and / holes.’ This triggers the speaker’s realisation that ‘anything abandoned / especially something creative makes me sad’ and their hopes for a more ambitious world:

and oh my god how many blogs will there even be online in 50 years’

time and have we got another 2000 years of blogging coming up

and shouldn’t we be setting up grander projects that will last

The final line – ‘Shall we put the kettle on?’ is what I actually say’ – is isolated from the piece. Ironically, in leaving these thoughts unspoken, they too become dead links.

‘The Burning of the Houses,’ which views the 2011 riots through the lens of social media, similarly captures a sense of disconnection between the online and real world. The speaker’s colleague ‘tweets that he can see / people smashing up a bus’ and ‘Anna is Facebooking furiously from Manchester / calling everyone bastards for doing this.’ Distressing events and emotions lose their impact and sound tinny when conveyed in this form, reflecting the helplessness of watching on as social order breaks down. The speaker’s cynicism is clear as order is similarly ‘restored’ at a safe distance: ‘[…] some of my friends / are linking to videos of kittens which must mean / everything is fine.’

‘Sonnet for Zookeeper’ lists repetitive actions in an online game (‘crocodile drop lion delete crocodile / drop lion delete crocodile drop’), highlighting the solitary, compulsive and immersive nature of life online. Again, there is sense that the digital world offers the illusion of a buffer against the difficulties of engaging with the real world. A footnote to the poem advises the player to ‘Try looking away from the screen’ and ‘Imagine you are driving at / night on a stretch of road lit by endless cat’s eyes / and have turned your headlights off.’ It is unclear if this guided meditation offers to draw the player away from an unhealthy habit, or to steel them for another round. Likewise, ‘Post’ offers a critique of contemporary living:

People in charge are needlessly cruel

and everyone is superstitious

remembering the once-great glories

of their golden days, trying to appeal

to our once-great memories

and failing. Death permeates it.

Farce permeates it.

Nostalgia feeds into this pessimistic outlook: the past is simultaneously glorified and hard to remember, placing it out of reach either way. But hope is not lost as the speaker draws strength from everyone who is ‘trying so hard to be great, doing / whatever they think is for the best’ This reiterates Bear’s opening celebration of the individual who can feel insignificant in, or disconnected from, modern society. Williams makes it clear that even though it feels as if ‘nights are getting darker’ and governments are ‘needlessly cruel’ there are pockets of magic to be found – in striving for what we believe in, in the idiosyncratic details of our relationships, and in creating and engaging with art as a way of hanging on to what it is to be human.

Reviews are an initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at – [email protected].

You can

You can

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.