If Jane Austen was a modern Welsh poet, her name would be Emily Blewitt.

This Is Not a Rescue (Seren) is an easy mix of dark and light, scooping its inspiration from the years between girlhood to marriage in Wales. These are old-fashioned yet ageless themes and Blewitt draws us in with her keen eye for quirkiness, a good ear for dialogue and her riotous delight in all things absurd, such as these lines remembered from a natty dance teacher who smoked during lessons and made personal comments:

Keep your eyes up

You’re blushing again

You’re as flat-chested as I am

if you don’t use it you lose it

if you don’t click this time, there’s something wrong with you

You’re too naïve

These poems are not naïve yet there is a total lack of pretention. For example, we have poems about chilling out on the sofa watching Paranormal Witness.

The house they find is empty, cheap

as chips and chipped all over: old panels, damp; nothing that a lick

of paint and some love won’t fix, they think. If it were me

I’d wonder what the catch was

Blewitt’s writing voice is endearing, sweet and self-deprecating. Some of the poems read like gossipy, literary conversations you might hear at college. Her favourite Austen male character says it all:

Only one satisfies:

Robert Martin,

bare arms like hams,

shirt sleeves rolled up

ready for supper.

Unbuckling his belt at the prospect of pudding,

he tells me there is no time for poetry

but he’ll keep me in steak,

love my brown eyes

that remind him of cows.

The majority of these poems throw themselves at the reader ‘like a kiss across a crowded room,’ but others are as unsettling as an egg lobbed at a window. There is an undercurrent of trauma, a sense of wrestling dark desires to self-destruct. In one poem she imagines leaping out the window, wondering if she will ‘fall the way cats do’. ‘When in Recovery’ is a very matter-of-a-fact poem about mental health:

Resist the urge to stick your knife in the toaster.

Be reckless enough to decent hills at a decent pace

but pick your mountains wisely. Get out of breath.

Focus on words, wasting them. Take citalopram –

four syllables, once a day, behind the tongue.

As her dance teacher says, ‘it takes a bit of grit to make a pearl’.

As well as personal suffering there is a sensitivity to others. I was moved by ‘Witness’, a poem which recalls the suicide of a young man, presumably a friend from school who played the clarinet and leaned on the desk laughing along with his peers:

Word spread quickly

that winter:

your car, abandoned,

the driver’s side

a gaping mouth

to your graceful vault

over the barrier

toward the river.

There is also a creepy, reoccurring figure of an abusive uncle who did something horrific to her mother. The effects burn into the skin of the next generation.

I am my mother’s daughter. I forgive

the man, my grandmother who let him in,

who called my mother a bloody liar

[…]

But I am my father’s daughter, too. I won’t

forget. Every night,

I bury the man alive and breathing.

My fires burn hotter than any crematorium.

One very short poem creates a cold sense of unease, showing a community in the midst of an unspecified crisis:

The village is out.

There are stars, houses

wrapped in snow. A search begins.

Although it is not referred too, it reminded me of when five-year old April Jones went missing in Machynlleth, mid-Wales in 2012. The whole community went out searching for the girl whose remains were eventually found. I lived not far away at the time and Blewitt captures so well that eerieness of a communal wound.

Unsurprisingly, I enjoyed the Welshness of the book, the sense of hiraeth: that nagging, tricky to define feeling of ‘the soul’s longing for home.’ The imagery of lighthouses, harbour walls, old boats, sand dunes, salt and a dog following the smell of chips into Cardiff town centre created a sure-footed sense of place. Being a Welsh person presenting herself to the English is shown in a somewhat self-conscious manner. Her English lover (a Saes), is a quiet figure in the poems; he seems obligating but disoriented and puzzles through her familiar streets ‘feeling lost to this west country that is no West Country’. Soon she finds herself as a bride to an English groom, and in ‘How to Marry a Welsh Girl’ she helps him navigate by describing a series of nuptial traditions. She uses humour to send up but also celebrate that aspect of her culture:

For a dowry you take what you can,

get what your given: the chapel, prolific sheep, jackdaws, circling

hills and black mountains, the usual ropey singing

at the pub they don’t speak English in, cheese and pickle

cocktail sticks, pasties, corned beef.

[…]

you won’t know

to carve a lovespoon, but I’ll tell you that birdsong in the morning

means luck; there might be donations of cheese, money, wool, bacon.

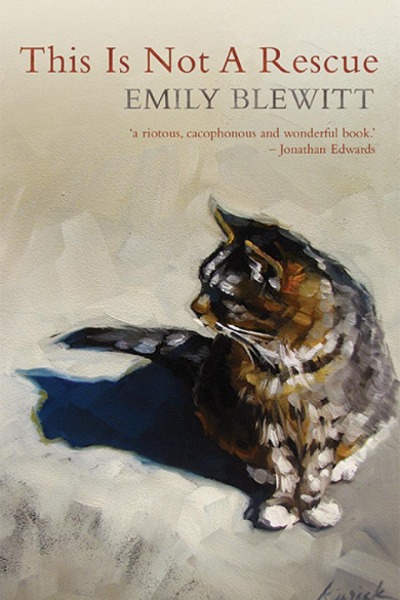

Poets at Seren are invited to choose their own cover. Blewitt chose a cat, a contemporary yet impressionistic painting of a tabby. It sits upright, face turned away in a concentrated, feline gaze. Its head hovers just above a large blue and black shadow that its dappled body casts on the pearl-grey carpet. This is a well-chosen picture. It combines a simple joy in domesticity with the shifting shades of inner darkness. The cat is the perfect symbol for this collection: a mysterious synthesis of softness and brutality.

Reviews are an initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at – [email protected].

You can

You can

Fantastic Review. I was starting to get sold on the book and then the mention of the ‘dog following the smell of chips into Cardiff town centre’ convinced me completely that I have to read it.