Tim Tim Cheng explores a world where endings and beginnings are inseparable in Yau Ching’s for now I am sitting here growing transparent (Zephyr Press, 2025).

Bilingual books curate a space of generosity. Placing work in the source language and target language side by side invites cross-cultural exchange. While monolingual readers must navigate unfamiliar sightlines, bilingual readers may engage more intimately with the creature that we call translation – a being that lives between and beyond two languages. Translated by Chenxin Jiang, Yau Ching’s for now I am sitting here growing transparent interrogates the interconnectedness between the human and non-human, word and world, where play manifests as intimacy, and intimacy as resistance. Through urban anti-eclogues, Yau Ching dances with death in its many masquerades.

And What’s Normal, Anyway?

The collection is divided into four sections: ‘Home 家’, ‘You 妳’, ‘Prose Poems 散文詩’, and ‘Death and Adventure 亡命與半途’. Each opens with a photograph of womxn – some distracted or forlorn in claustrophobic, tattered urban settings; some nonchalant, even lustful, in bridal veils and tiaras against studio backdrops. These images reflect Yau’s multimodal cosmovision, shaped by her well-wrought hybridity as a queer filmmaker, newspaper columnist, and academic across New York, Tokyo, Taiwan, and British-colonial and post-Handover Hong Kong.

Yau does not wait to problematize normality. In ‘Hong Kong Malady’: ‘health itself is just numbness / deadness to the world’, suggesting that our awareness of the world – of its injustices, its alienations – can itself be a kind of sickness. This calls to mind Sanah Ahsan’s analogy rooted in liberation psychology: ‘If a plant were wilting we wouldn’t diagnose it with “wilting-plant-syndrome” – we would change its conditions’ (2022). We are only as healthy as our environments.

The Last ‘No’!

Though a sense of crisis simmers throughout the book, Yau maintains an erudite, critical voice with a lightness of touch. She acknowledges complicity in late-capitalistic, neo-liberal societies. In ‘No city’, ownership is illusory, and language – like the world’s order – fractures:

Whenever I visit a city

I think about buying a flat

Whenever I go to a new place

I think about settling down

I’m looking for what I imagine

the doable can’t be attained

impossible human

[…]

So many people

there’s no way to live

what’s left is no thing

that makes us

no body

if not a body

then just a no

After serial negations, the last ‘no’ lands somewhere between despair and transcendence. I recall the Buddhist idea of ‘emptiness’, where the ‘non-self’ exists in a ‘neither the same nor different’ relation with everything else (Ziporyn, 2014). This aligns with Hong Kong’s ‘political ecology’ and ‘translational activities’, where, as Zhao and Geng write, ‘progression of human history can be viewed as a movement towards an even greater loss of control over the processes that affect human beings and their environment’ (2024).

Blurred Lines

In the translator’s note, ‘Yau Ching’s Self-Translating poems’, Jiang elucidates that Yau writes ‘in Cantonese-inflected standard Chinese’. To translate this work into English, Jiang notes, is ‘to bring them into a space that they already uneasily inhabit’. Though most Hong Kongers ‘speak Cantonese as their main language’, ‘English was [Hong Kong]’s only official language’ until 1974, when Chinese was formally recognised. In ‘You and Us’, Yau writes:

Modernity colonized you

You want to be us but

you despise us

Colonialism modernized us

It wrote literature backbone trust and history

into commerce reason the nimble formula of rule

of law of the only impartial

free place where Chinese people and foreigners lived together

inside us while we

have never been modern

[…]

We’re used to

debris facing backwards while being dragged forward

[…]

we are

debris layer upon layer of skin and flesh with pickled vegetables

flayed from us picked clean

feed our crippled ruined city

spouting red bubbles if you think for a minute you’ll wonder

why your flowers are

so red today

Here, Yau blurs the distinction between the human, non-human, and spatial, depicting a cyclical relationship between history and nature. ‘You’ and ‘we’ stare at each other only to find a mirror: ‘Modernity colonized you’ / ‘Colonialism modernized us’. Symbiosis becomes parasitic. Our ‘bubbl[ing]’ blood nourishes ‘your flowers’. Alienated, abstracted into a vessel, ‘we’ come to the collapse of linear time: ‘Chinese people and foreigners lived together / inside us […] / We’re used to / debris facing backwards while being dragged forward’.

Playtime.

In ‘Queerness as Translation‘, Mary Jean Chan writes: ‘I want, instead, to inhabit a state of play – a form of playtime – where time dissolves and there is only being, breath, and the myriad of languages we allow ourselves to inhabit and speak’. Yau’s work, too, longs for such play, a dissolving into one’s surroundings. In ‘Spacetime’:

Time is like a shadow on the road

The English word longing has length in it

I long—long——for you

My sleeves pant legs lengthen fingers and toes lengthen

every single hair on my head and brow

stretches downwards trailing on the ground like banyan roots

[…]

Loneliness in Chinese is empty

An empty sheet of lined paper

“Hey you, three more love poems!”

translucent it has no shadow

the world is big and for now I am

sitting here growing transparent

No words can fill up

how empty I am on all sides

and in front and behind, how long

The poem’s irregular rhythms evoke a kind of stretching – of time, body, longing. In ‘Moon’, the poem plays with homonyms: the lover’s name, ‘Mona’, echoes the Chinese homonyms ‘moon’ and ‘month’ (月). Linear time and collective progress are abandoned in favour of individuals’ proximity and tenderness:

why does our way of telling time

always forget the moonlight?

I’ve no way to complete the circles of life

when planting

onions and peppers and perillas

In this moment your hair is splattered like a Pollock autumn

sliding

into a time that’s neither yours nor mine

someone is busy talking about stars expanding, which is to say contracting

while we spin like spaghetti in a black hole

The Final Word

Yau elevates the carnal to something more-than-human. Urban sensualities do not escape nature’s pattern. As Schnabel notes: ‘human activity takes place not within human cultures, but within inseparable “natureculture” assemblages’ (2014). Yau’s poem ‘Embrace’ merges the physical and metaphysical, distilling this interplay into a final word:

I embrace you

at an angle that mimics

the arc of a cat’s softness

After savaging

the neighbourhood butterflies

it’s content to return to

your roundness

inside it a teeny-tiny

quiet little

so hard-beating

core

Inversions on Death

In the final section, ‘Death and Adventure’, Yau grapples with ‘the unknown and unknowable’ through elliptical phrasing. Jiang’s translation embraces this with ambiguity and wit. The poem ‘I am a Foot’ reads like ‘afoot’, inverting a popular philosophical axiom:

what Yau Ching is

I am always over-acting the part

some things some tasks some likes and dislikes

on limited repeat

unlike wind flowers cats or even grass

There is no me therefore I have no limits

a foot cannot step twice into the same river

before it steps out   it has already become a different foot

how to become this foot

how to bear each stepping in and out   every moment

the river is different

every inch of the foot

has already become the river

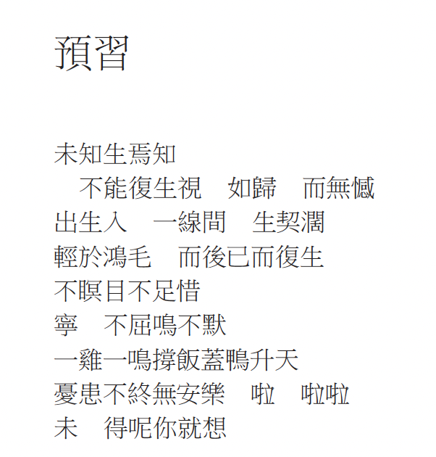

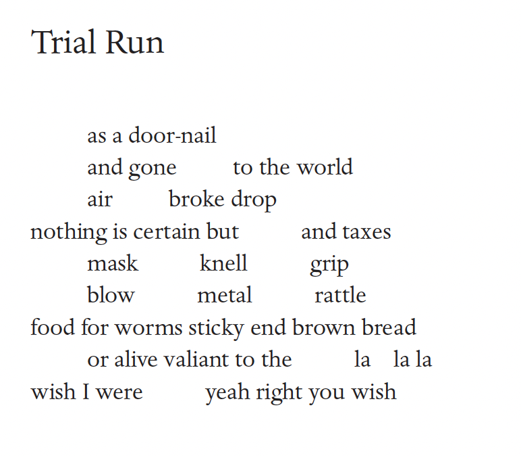

From an anthropocentric perspective, death is feared. But for Yau it is part of ecology: ‘learning not to fear death / is the only way to know life’ (‘Unknown’). In ‘Trial Run’, Yau and Jiang push the limits of language, omitting the poem’s subject entirely and forgoing literal translation. In doing so, they create a ghostly presence that merges with the white space of the page.

Beyond Sameness…

‘Trial Run’ creates a visual riddle. By inviting the reader to decode the missing words and fill in the blanks, the poem forces bilingual creativity and reader involvement. Those with different languages can experience the poem in diverse ways. As a bilingual user of Chinese and English, I was intrigued. What makes ‘Trial Run’ an iteration of ‘預習’? The only ‘word-for-word translation’ is ‘la la la’ (啦啦啦) and ‘you wish’(你就想). While ‘yeah right’ (得呢) qualifies as ‘sense-for-sense translation’, the rest of the poem is translated ‘form-for-form’ (Ip, 2024). Chinese meanings leap across the threshold of English, shapeshifting beyond sameness.

Such Radical Hope!

So much more could be said about Yau’s poems and Jiang’s translation, which interrupts ‘binaries’ such as ‘nature/culture’, ‘east/west’, ‘life/death’ and ‘form/content’ (Schnabel, 2014). The inquisitive and pluralistic voices in Yau’s poems resist easy categorization, asking if we ‘know after the apocalypse life will keep / growing’ (‘Poem About Being Young’). Such radical hope is grounded in one’s material relations with the environment, where endings potentiate beginnings. As in ‘Dissolve into Wind’, Yau’s vision of cyclical time and material interconnectedness comes into sharp focus. Here, even incomplete phrases, like ‘is so’, suggest a world where endings and beginnings are inseparable, and historical process resists closure:

(Maybe you don’t know how to be weary

Passing by you fell in love with stones by the wayside

you’d forgotten that stones speak of tiredness, dissolve into wind)

[…]

there’s something that

while being completed

can’t be improved accumulated

inherited revisited

it’s no wonder history is so

Tim Tim Cheng is a poet and teacher from Hong Kong, currently based between Glasgow and London. She is the author of the pamphlet Tapping At Glass (VERVE, 2023), which was one of Poetry Society Books of the Year. Her debut collection, The Tattoo Collector was published by Nine Arches Press in 2024; it explores the relationship between the body, ecology, and class.

She is a co-editor of Where Else: An International Hong Kong Poetry Anthology (VERVE, 2023). Her poems appear in The Rialto, POETRY, Poetry London, Magma, among others. She has performed for BBC Scotland, StAnza Festival, Singapore Writers Festival, National Poetry Library and the likes.

She is a WrICE fellow (awarded by RMIT University), an Ignite fellow (Scottish Book Trust), a member of Southbank Centre’s New Poets Collective 2022/23, and a mentee under the Roddy Lumsden Memorial Mentorship scheme. She edits, translates between Chinese and English, and writes lyrics. timtimcheng.com

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.