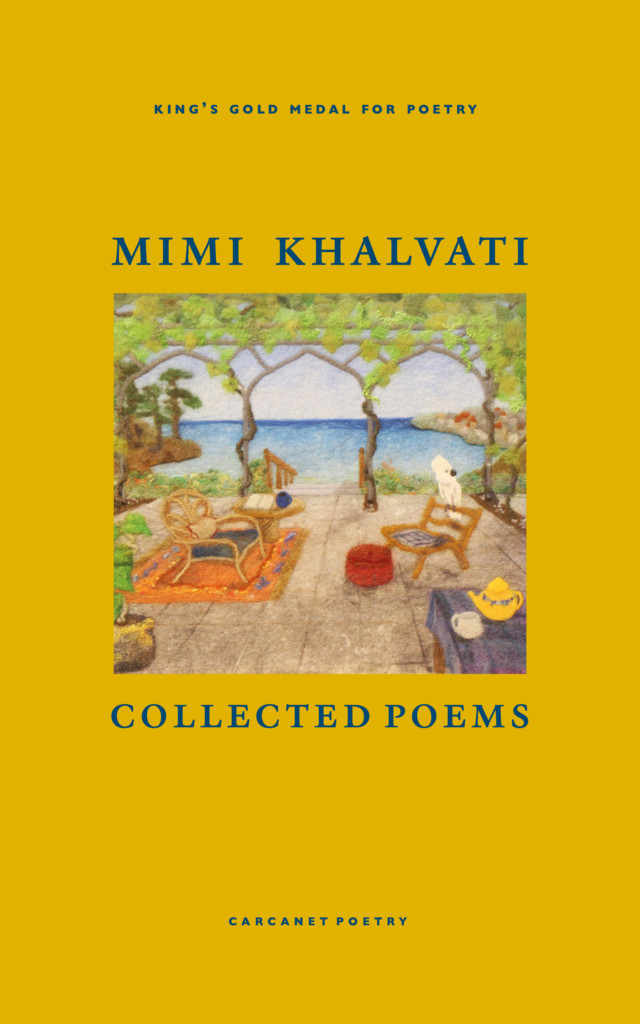

Roshni Gallagher Explores Light, Love, Language and the Self in Collected Poems by Mimi Khalvati.

Mimi Khalvati is a poet of light, love, absence, and the many facets of self. Her various collections span from In White Ink, published by Carcanet in 1991, to her 2019 collection Afterwardness. The publication of this Collected Poems comes on the heels of her being awarded the King’s Gold Medal for Poetry and contains previously uncollected poems. Khalvati’s lyric poetry pays particular attention to the routines of daily life, daily emotions, and at times takes a child’s eye view. These poems speak of a sensual, interconnected world, where images of flowers, fruits, and animals populate the page.

Home as Empty Space

Khalvati is a poet who writes primarily from real life – in a 2024 interview with Carcanet ahead of the publication of this book, Khalavti states ‘I’ve never actually invented anything in any of my poems, to my knowledge. I think everything is literal, everything is pretty much autobiographical’. Though born in Tehran, Khalvati was sent away to boarding school in the Isle of Wight at age six, where she grew up with few memories of her mother or of those formative years. Absence and loss are a defining feature of her collections, and in the poem ‘Writing Home’ from The Chine (2002) she writes: ‘As far back as I remember, ‘home’ / had an empty ring.’ It was ‘an empty space / I sent words to.’ Language creates a further division between the speaker and the ‘home’ of their childhood. Growing up Khalvati lost her first language, Farsi, and learnt to speak English. The poem concludes, ‘under the crab-apple tree, taking root, / words in a mouth puckered from wild, sour fruit.’

In ‘Scripto Inferior’ from Afterwardness:

To know your story is to understand

not only who you are and where you come from

– even if some imaginary homeland

is all you know, shall ever know of home –

but is also to understand the nature

of story …

Unable to easily define their life story, the speaker goes on to state that foisting ‘a love of narrative’ onto one who does not possess ‘near total recall’ of their past is ‘unkind’. Instead, the poems are propelled by lyrical, hazy memory and language itself. In the interview with Carcanet, Khalavti describes her approach to writing poetry as ‘trying to use the language well, being more interested in the process, in how I write, rather than what I write’.

Playing with Form

As the poems are propelled by language, they are also born from form, and Khlavati has an intelligent and masterful grasp of form, from Ghazals to villanelles. Khalvati is particularly at home when writing sequences, perhaps because without a narrative ending there is always more to say – these are poems that capture the fabric and feeling of life. In her second collection Mirrorwork (1995) Khalvati experiments with a free verse sequence of poems entitled ‘Interiors’ based around the work of the painter Édouard Vuillard, whose process involves painting from memory. Artists and writers are referenced throughout these Collected Poems and Khalvati is not a poet who writes in isolation from the world. Partly drawn to his art for the resemblance between Vuillard’s mother and her grandmother, in section II. Studies for the Workroom, Khalvati writes:

we will feel,

lodged long before we enter,

like a bass note to the moonlight,

a memory forgotten that will not go away,

the ceiling of a presence,

a company, a solitude,

These interiors are inhabited by memory and absence, where we sense the presence of people who have passed through before us. The use of the collective pronoun ‘we’ throughout the sequence encompasses the speaker, us as readers, and perhaps also this ‘presence’ that inhabits the paintings. There is also a sense of holistic cohesion and acute awareness of space in this sequence:

Over doorsills, tiles,

from the intensity of borders

to the middle ground and back again,

taking carpets at their own speed,

we move along their pathways;

With an acute focus on the ground, we move through these dream-like spaces with precision. Khalvati notes the different temporal qualities of space. Borders and thresholds such as the ‘doorsill’ have an ‘intensity’ that is diffused as we move back to the ‘middle ground’ and take ‘carpets at their own speed’. The room itself dictates the pace with which we move through it, eroding the separation between the material world and the self.

Khalvati builds on the rhythm established in Mirrorwork in her third collection, Entries on Light (1997), which is a singular book length poem that takes light as it’s subject. In the poem we glimpse moments of intimacy and fleeting thoughts, that rise and vanish in the poems’ awareness. There are indentations of white space at the beginning of every other line, which wrap the poem in silence and enhance the fragmentary nature of the sequence. There’s humour and strangeness here too, where light itself becomes a character in the poem. She writes: ‘Light’s taking a bath tonight’… While light is personified, the mind too is akin to nature, and Khalvati excels at drawing similarities between the natural landscape and the inner landscape of self:

the mind has taken flight

left a birdless stretch of grass

so much larger than itself.

Here the white space embodies a creative and intellectual leap as well as loss.

Her most recent collection Afterwardness is also a sequence, but of Petrarchan sonnets. These sonnets strike different tones, from elegiac to playful, but broadly circle the themes of language, writing, and early trauma. The poem ‘Petites Salissures’ references back to Vuillard and his, ‘small sketches’ that reproduce ‘the distortions, elisions and arbitrary / vanishing points that memory dictates.’ A commitment to honouring and writing through these ‘distortions’ is a thread that runs from Khalvati’s early work to her most recent.

The Threshold of Landscape

There is a strikingly strong sense of place in these Collected Poems. From the chine in the Isle of Wight to the Mediterranean, Khalvati wonderfully captures the heart of landscape. In ‘The Mediterranean of the Mind’ from The Meanest Flower (2007) she writes of ‘[s]mall and profuse, white figs’ and ‘[l]emons’ that have ‘spilled / to circle their trunks’, noting the ‘frugality / and generosity both of the village / and landscape.’ She is attuned to the sounds and silences of place:

the big church

in the village square, forever

clanging its bells – heard in London

if you use the public phone –

Khalvati’s landscapes are always in touch with other places, through memory, story, or people.

There is also a sense of language and writing as a place in and of itself, one where a reader might experience life more acutely. In ‘Writing in the Sun’ from Mirrorwork she writes:

writing in the sun

is what would make

re-entering a room

as cool, hushed,

as walking into sleep

if sleep were

a marble void

on the threshold of cathedrals.

Writing is a way to enter a different state of consciousness – ‘blinded’ by ‘sun’ and ‘shade’, it is a liminal space of possibility and spirituality that one can drop in and out of. Where one might ‘take […] life in hand’ and build a home at the ‘threshold’ of wonder and absence.

Childhood, Childhood

In The Meanest Flower, Khalvati writes: ‘There’s nothing I love more than childhood, childhood’, forming childhood as a space where one is closer to nature, and better able to listen to the world:

As if they were family, flowers surround you.

As if they were a story-book, they speak.

They speak through eyes and strange configurations

There is a directness to the community found in nature – it is a form of connection that exists outside of human language. We can engage in conversation through ‘eyes and strange configurations’ without having to confine or subject ourselves to the limitations or misinterpretation of our words. And one doesn’t need to be in their ancestral country to find themselves at home. In ‘I love all things in miniature’ from Entries on Light:

they

recollect a child’s eye view

of a small world inside a large

in which small things might represent

the large …

Khalvati is interested in what she describes as the ‘quiet monotony’ of daily life (‘Iowa Daybook’, Child: New and Selected Poems 1991-2011), and by taking a ‘child’s eye view’ of the world she pays attention to the ‘small things’ that could easily be overlooked. In ‘Reading the Saturday Guardian’ from The Weather Wheel (2014), the focus on a ladybird and ‘(croissant) flake – // twice her size’ that ‘toppled over the rim of the Guardian’ is a delightful example of this. The attention she pays to this image allows the reader to take pleasure in and experience the texture of daily life with fresh eyes.

Lovely as the Moon

Kha lvati writes intimately and with great care about the lives of women, where some of the most moving and striking poems in this book are the elegies written to the speaker’s late grandmother and mother. In her 2024 interview with Carcanet, Khalvati says that because her grandmother spoke ‘no English and I spoke no Farsi’ they built their close relationship through what she describes as ‘these silent dialogues’. In the poem ‘Rubaiyat’ from In White Ink, Khalvati writes:

My grandmother would rise and take my arm,

then sifting through the petals in her palm

would place in mine the whitest of them all:

‘Salaam, dokhtaré-mahé-man, salaam!’

‘Salaam, my daughter-lovely-as-the-moon!’

Would that the world could see me, Telajune,

through your eyes! Or that I could see a world

that takes such care to tend what fades so soon.

The tenderness of the gesture is just as important as what is spoken. And by capturing the grandmother’s small movements, the speaker ‘tends’ to and mourns the memory of her. Amid the delicacy, and ‘sugar’ of this poem, there is a further question of inheritance and heritage, where the phrase, ‘whitest of them all’ introduces a subtle element of racial tension to the poem. Whiteness, here, is desirable and layers onto the loveliness that the grandmother sees in the petal, the moon, the speaker and perhaps part of what is not seen in the speaker by the world at large. In a poem so ‘lovely’, Khalvati raises, then disrupts, the iconic image of the ‘lilacs’ utilised throughout Persian tradition. Subtly, and with devastation – these fragile complexities are laid out for sifting.

Writing after her mother’s death in ‘Tears’ from The Weather Wheel, the speaker reflects also on the centrality of her mother to her life: ‘I measured distances by her. My mother my compass, / my almanac and sundial, drawing me arcs in space.’ This profound grief is compounded by a further loss of heritage, story, and memory, and in ‘Granadilla de Abona VI’, there is the devastating couplet: ‘Her family history died with her, none of it lives in my / or my children’s memory. We are yesterday’s people’.

Then Sing, Sigh and Sing

In the long poem ‘Iowa Daybook’, the speaker expresses the wish to luxuriate in ‘patient’ close reading, so that one might ‘live with Dante, say, / months at a time’. And reading these Collected Poems I feel I have had the rare and precious honour of living for a month with Khalvati’s mind – her passions, language, and memories.

What Khalvati does best is map what it is to live a connected, lucid, sensuous life despite experiences of early separation or the traumatic loss of one’s culture. She is a thoughtful poet, attuned to the joys and sorrows of the world. In Afterwardness she writes:

Where do memories hide? the pine trees sing.

In language, of course, the four pathways reply.

What if the words be lost? the pine trees sigh.

Lost, the echo comes, lost like me in air.

Then sing, the pathways answer, sigh and sing

for the echo, for nothing, no one, nowhere.

And the poems, do.

Image: Kirsty Cook, 2022.

Roshni Gallagher is a poet from Leeds living in Edinburgh. Her debut pamphlet Bird Cherry is published by Verve Poetry Press. She is a winner of the 2022 Edwin Morgan Poetry Award and the 2022 Scottish Book Trust New Writers Award. In her work, she explores themes of nature, memory, and silence. Find her on twitter and instagram or at roshnigallagher.com

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.