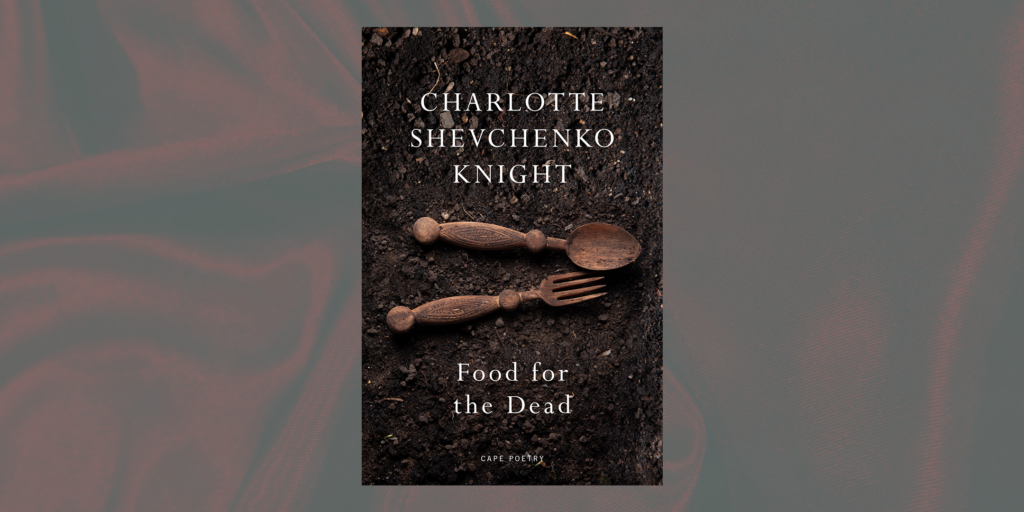

Welcome to our Forward Prizes 2024 ’How I Did It’ series. This year we asked poets shortlisted for the Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection to write about the inspiration behind one of the poems from their chosen collection. Here’s Charlotte Shevchenko Knight on what inspired her to write the poem ‘life & no escape’ in Food for the Dead.

My recollections of Valentina are vague, which I blame on the distance. She lived in Donetsk most of her life, and I’d only visit Ukraine every other school holiday. With each summer that passed, my grasp on Ukrainian dwindled and our conversations became increasingly limited. She began to retreat to her room more often, which I mistook for shyness.

As I got older, I’d learn that my great-grandmother had been living with dementia and would keep to her room, in part, so that I would not witness her undoing.

In my most vivid memories of Valentina, we are sat side by side in silence, exchanging the occasional smile.

Or there is the image of her hand reaching over to mine, its blue veins protruding, and my fear that it could hurt to hold her hand, that my grip might stop her blood.

Perhaps that fear of holding her hand is what propels ‘life & no escape’.

The poem consists of seven couplets, so fourteen lines, which could mean it is a sonnet depending on your beliefs around sonnets, or it could mean nothing at all.

What I can say is that the motivation behind form was not the sonnet. Rather, it was that couplets felt apt when writing a poem about Valentina. Couplets go together, like two women sat side by side on the porch, enjoying a forever summer.

Couplets hold each other’s hands in thought, sustaining that thought across its line break. But my concern in this poem was to undermine that lucidity. Take as an example the following lines:

[…] to feed

the chickens perhaps but there were

no chickens to dig up potatoes

but the ground lay bare

The couplet presents the reader with an image, say, chickens, or potatoes, but by the following line it takes them away.

The couplet here is a hesitant hand, a thought undoing itself. This is what perversely sustains the poem, much like the star which can be seen but which is not.

Towards the end of her life, Valentina’s memories, her sense of time, would often undo themselves.

We would be in the kitchen, for example, drinking tea, when she would be snared by terror. Who was the girl sat across from her, what was she doing in her house? Was this her house? Where was the farmyard of her youth, the grazing goats she adored?

Valentina passed away in December 2020. I wasn’t there. As I understand, she was staying in a motorway motel with my grandmother and became confused by her surroundings.

The poem places itself – places me, the grandchild – in that final moment. Why?

Partly because I couldn’t be there – travel restrictions meant I couldn’t attend her funeral, couldn’t go through the 40 days of mourning that would usually be observed.

Partly because a year on from her death, I travelled to Ukraine to mark the anniversary of her loss and came across a country totally unfamiliar to me. The level of covid restrictions differed greatly from the UK – with temperature checks at every supermarket, vaccination documents being shown at cafés – but I also noticed armed men patrolling neighbourhoods and shopping centres, a sign of what was to come.

The landscape of my childhood summers seemed to have vanished. I thought of Valentina, lost in time, and wanted nothing more than to be with her on the porch.

The poem places me alongside Valentina in the motel, I suppose, because I hoped that I could hold her hand. If not in the past, then in the poem.

Which brings me to its title, lifted from Anne Carson:

My brother once showed me a piece of quartz that contained, he said, some

trapped water older than all the seas in our world. He held it up to my ear.

‘Listen,’ he said, ‘life and no escape.’*

Life and no escape is the condition of the poem. Here in the poem I am with her, despite having not been, amongst all this doing and undoing. This can be the place where I reach for her hand.

*Anne Carson, ‘The Wishing Jewel: Introduction to Water Margins’, Plainwater: Essays and Poetry.

life & no escape

after Anne Carson, i.m. Valentina Zhmur

she would open the front door & forget

where she was going to feed

the chickens perhaps but there were

no chickens to dig up potatoes

but the ground lay bare the motorway

would buzz nearby the sky would stand

blue unfamiliar as would the mirror

as would the grandchildren dressed

in denim tugging her sleeves asking her

to come inside there would be no cosmic

reasoning for it first she would forget

their names then she would forget hers

like a star dead in the sky they could see her

but she would no longer be there

BIO

Charlotte Shevchenko Knight is a poet of British and Ukrainian heritage. Her debut pamphlet Ways of Healing was a winner of the 2022 New Poets Prize. Her debut collection Food for the Dead, published by Jonathan Cape, was a winner of the 2023 Eric Gregory Award, and is shortlisted for the 2024 Forward Arts Foundation’s Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection. Shevchenko Knight is a PhD student at Manchester Metropolitan University and is based in York.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.