It’d be easy to talk about the long awaited fourth collection from Ben Lerner as excellent, or sophisticated, and both would be true, however I am more inclined to think of The Lights as a vertex, a plot on a chart to a heavenly body that Ben Lerner’s next collection, or the next, might take us to. I think I know why I think this but let’s see if I can take you there with me. Nobody hold their breath.

First Things First

Let’s get something clear so we understand each other from the outset. The first time I read Lerner I was somewhat intimidated. He was virtuosic. So good that at some point I couldn’t bear to read him anymore (a reaction Lerner had anticipated in his earlier monograph The Hatred of Poetry – albeit not for this reason). I realize this is not a criticism of Lerner’s work so much as an acknowledgement of its very goodness, but here I am, unburdened.

The Lights, though, appears to be something new – infusing as it does Lerner’s acrobatic poetics with a good helping of humanity and perhaps even (whisper it) sentiment. For me, The Lights is two things: 1. further evidence Lerner has the tools to write some of the most accomplished anglophone poetry of our time and 2. an indication his evolution as a poet is pointing in an important direction.

So, I’ve sworn off using the word ‘genius’, but there are three poems in this collection I marked with an ‘m’ in a little triangle for ‘masterpiece’; ‘The Son’, ‘The Lights’ and ‘The Rose’ (p18). For my money, this is what truly great poetry looks like. Take for instance, this excerpt from ’The Lights’:

that they are here

among us, that they love us

that we invited them

in without our knowledge

into our knowledge, its cavities

[…]

in us, that they are part of our sexual life

that they are reading this

In a piece ostensibly about aliens (that doesn’t talk about aliens), Lerner’s speaker instead gives us the familiar, the unfathomable, the petrifying ‘they’. He spends eighty lines braiding the deep uncertainty, and fear, involved in our relationship with the unknown (both external and internal) and manages to land the whole piece on a pinhead with the third section of this poem that contains no less than sixteen expositional uses of ‘that they’. Lerner’s ‘they’ here is the unknown itself, the alien. But it’s also our own dead, our own children, doesn’t matter – here ‘they’ are now among us. Lerner’s speaker even has them care about us, at the same time as considering our destruction. Heck, ‘they’ might even be us. It is a finale that is at the same time wondrous and armageddon, human and magical, terrible and, in the end, somehow full of hope.

Elsewhere Lerner explores thematic forays into fatherhood (in ‘The Camperdown Elm’ & ‘The Readers’), which feels like a first as do the more essayistic offerings (in ‘The Curtain’ and ‘Untitled (Triptych)’). Lerner does give space to a good deal of recollection from childhood, and this is welcome as well as noteworthy in the context of a maturing (mellowing?) poet perhaps previously more likely to wow than to wonder.

The Game

That Lerner is as playful as ever in his use of language throughout is no surprise. He frequently fragments or layers thematic elements to create collage and uses humour to good effect; noticing it ‘[s]trange how “poet” and “cop” are anagrams’, ‘strange that “song” and “smoke” are homophones’, that ‘glass […] is made by heating grass into a liquid’ (‘The Stone’), and later has ‘soft glass bending in long meadows’ (‘The Media’).

And it has always been to some extent a game for Lerner, except that now it’s a game in which he has more skin by dint of his young family (the book is dedicated to his daughters) and his responsibilities toward them. This has two notable effects on the work; a softening or maturation in terms of his themes and objectives, and a muting of some thematic elements perhaps trickier to share at bedtime (a function he explores explicitly in ‘The Readers’ and alludes to elsewhere). I can empathize as a father with the need for gentleness and tonal restraint regarding creative output – Lerner here embodying the role of protector – but would like to see what he writes when it becomes acceptable to be Ben Lerner the whole person, complete with his mistakes, regrets, desires, distresses, and other fallibilities more fully addressed in his poetic work.

Let’s look at ‘The Media’ where there is some indirect attempt to address this:

Otherwise you’re mixing pills and gin and your friends are debating if it constitutes a true attempt,

recklessness, a cry for help, before deciding it makes no difference, it’s pain behavior, he has to be

checked in, monitored, sponsored, set to music. Anyway, the girls are down and I can talk. I’m just

clicking on things in bed, a review by a man who says I have no feelings and hate art.

On Feeling…

I do not think that Ben Lerner nor his speaker has ‘no feelings and hate[s] art’ (‘The Media’), far from it. It seems he struggles deeply with the often-conflicting roles of artist/earner/parent and with what is at stake in that struggle. Everything is on the line here – the speaker unable to fully reconcile the demands these roles make upon them, he becomes marooned while shuttling between these stations – as if playing musical chairs and being left to contemplate the failure, the loneliness, when the music stops.

I am interested in this experience of isolation – when the music does in fact stop. It is a deeply affecting passage, because it looks precisely like the ‘pain behavior’ he refers to. Here Lerner’s speaker is like us; vulnerable, afraid to be brought back down to earth, or beyond, afraid to be told, after everything, he’s no good. These are the difficulties Lerner seems to begin to both tackle and avoid as he is inevitably seen to be jumping in and out of the speaker’s voice: ‘And it’s me, Ben, just calling to check in’ (‘The Media’).

So, what does Lerner’s speaker lose in the course of this struggle? There are some clues with a healthy smattering of ‘vaguely erotic’s (‘The Dark Threw Patches Down Upon Me Also’) and several other underexplored references to desire scattered through the collection. We find desires relegated to the general in ‘Auto-Tune’, elevated to the altruistic in ‘Untitled (Triptych)’, hidden from view in ‘The Readers’ and ‘The Grove’, and destroyed altogether in ‘The Lights’:

I hold the back of his head and see

unexplained lights over him

that love makes, even if what I want in part

is to be destroyed, all of us

at once, and so the end of desire is caught in it

I think it is ok to want that …

…& Destruction

Here Lerner’s speaker envisages a collective end, and along with it the end of the problem of (his own?) desire. The absoluteness of this as a solution indicates deep difficulty in the encounter with (or consequences of) desire. Exactly as a person in profound emotional pain might posit their own ending as the only solve. This is nothing if not ‘pain behaviour’. But what aspect of who’s desire is Lerner’s speaker intimating? Or is desire in its entirety that which might usefully be destroyed, and if so – why? What is the unsayable, unbearable alternative?

Lerner’s speaker has us believe he can feel ‘it getting away from me’ (in both ‘The Dark Threw Patches…’ and ‘The Rose’) but the collection never looks like doing anything close to that. Perhaps a Ben Lerner collection which more freely explores what happens when it does, or why it does might be possible, even necessary? Holding my breath for that might be a bad idea, but buying his next book might not. The Lights cements Ben Lerner near the top of my ‘must buy’ list, he should be on yours, too. More of this.

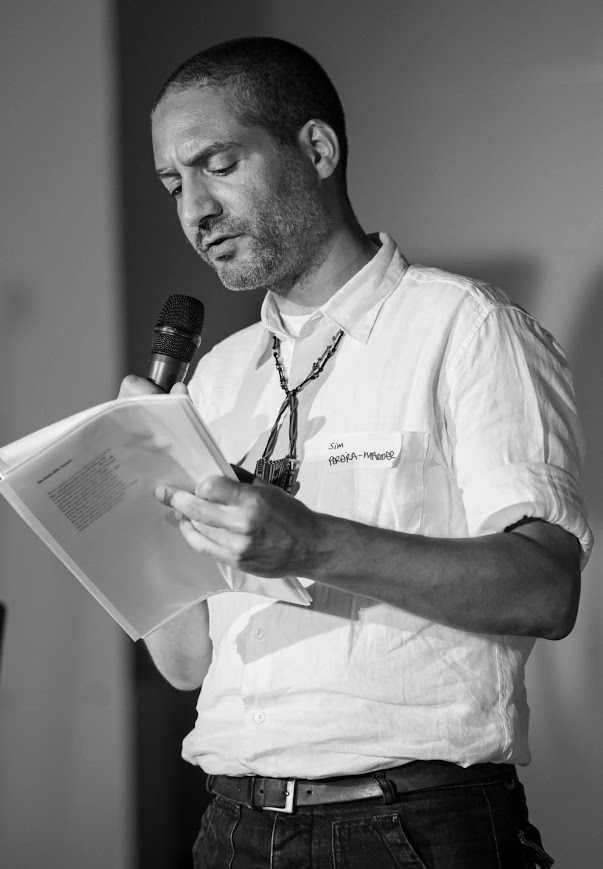

Sim Pereira-Madder is a British born poet based in London. His work centres otherness, repair, experimental form, and the domestic realm. An Obsidian Foundation alum, and Poetry School intern, he is currently studying for his MA in Writing Poetry. His work appears or is forthcoming in Magma Magazine, Ink Sweat & Tears, Propel Magazine, La Piccioletta Barca, and Wet Grain, and is being corralled towards a debut pamphlet. This is his first review. You can find him on the internet at threetruewords.com or on instagram at @threetruewords.

Image credit: josimarsenior

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.