It’s been a superb year for ‘little shapelets’ and their ‘sprinkling of white space’. Funny, painful, complex, adventurous, elegiac, innovative, insightful and enduring, the books we have chosen to celebrate here represent just a small selection of the marvellous work we have read and loved over the past twelve months. Below, in alphabetical order, you will find a few of our favourites, in short reviews written by our staff, and a longlist of a hundred.

It’s fashionable to decry the state of contemporary poetry – it feels like every year someone takes to the pages of a broadsheet of literary magazine to confidently announce the end of the genre, the loss of craft, its general amiss-ness. In truth, it’s stronger and more vibrant than ever; nothing is out of bounds, nothing is impossible, nothing is beyond its reach. We’ve chosen books that explore parenthood in all its forms, d/Deafness, multilingualism, Windrush, wild swimming, loneliness, cricket, pearls, Freud, masculinity, games, spells, gay shame, wasps, mass shootings, Mad Men and myth.

Having binned all the rules, let’s dare to say it out loud: contemporary poetry is in a glorious state.

WB = Will Barrett, ED = Ema Dumitriu, JC = John Canfield, SC = Sally Carruthers, AL = Ali Lewis, MS = Martha Sprackland, ML = Maria Lewandowska, AP = Andrew Parkes

POETRY SCHOOL BOOKS OF THE YEAR 2018

The Perseverence by Raymond Antrobus (Penned in the Margins); Rising Stars: New Young Voices in Poetry by Ruth Awolola, Victoria Adukwei Bulley, Abigail Cook, Jay Hulme, Amina Jama (Otter Barry); The Republic of Motherhood by Liz Berry (Chatto); Pamper Me to Hell and Back by Hera Lindsay Bird (Smith|Doorstop); Venus as a Bear by Vahni Capildeo (Carcanet); Any Change? Poetry in a Hostile Environment edited by Ian Duhig (Strix); Their Lunar Language by Charlotte Eichler (Valley Press); Passivity, Electricity, Acclivity by Ella Frears (Goldsmiths Press); The Built Environment by Emily Hasler (Pavilion); American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin by Terrance Hayes (Penguin); Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God by Tony Hoagland (Bloodaxe); Isn’t Forever by Amy Key (Bloodaxe); Us by Zaffar Kunial (Faber); The House With Only an Attic and a Basement by Kathryn Maris (Penguin); The Triumph of Cancer by Chris McCabe (Penned in the Margins); Anomaly by Jamie McKendrick (Faber); Working Class Voodoo by Bobby Parker (Offord Road Books); Jinx by Abigail Parry (Bloodaxe); Feral by Kate Potts (Bloodaxe); Natural Phenomena by Meryl Pugh (Penned in the Margins); Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting by Shivanee Ramlochan (Peepal Tree); Rabbit by Sophie Robinson (Boiler House); Soho by Richard Scott (Faber); Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith (Chatto); Green Noise by Jean Sprackland (Cape); Three Poems by Hannah Sullivan (Faber); The AQI by David Tait (Smith|Doorstop); The Barbarous Century by Leah Umansky (Eyewear), Tenuous Rooms / Solo for Mascha Voice by Jack Underwood (Test Centre).

The Perseverence by Raymond Antrobus (Penned in the Margins)

The Perseverence by Raymond Antrobus (Penned in the Margins)

I have a personal connection to this book. The author was thought to be dyslexic with severe learning disabilities until his deafness was discovered at the age of six. I lost part of my hearing when I was eleven months old, didn’t talk until I was five years old, and was thought to suffer from learning disabilities. I remember angrily smashing my hearing aid at school when I was eight, inchoate with rage, only beginning to understand that the problem wasn’t whether I could hear, but whether THEY were listening. This book is far bigger than d/Deafness, however, localising identities in the entire bodyscape, be they physical, social, racial, class or religion-based. The Perseverence starts off like a modern-day Milton (‘Echo’), ends with ‘Happy Birthday Moon’, a tender, deceptively simple pantoum about the author’s father (a keystone of the book), and ranges everywhere in between. It channels Danez Smith, Malika Booker and Caroline Bird, in formal poems, erasures, free verse, innovative use of Makaton symbols, translation, prose, and a blackout version of Ted Hughes’ ‘Deaf School’; probably the best poem I read all year, and it doesn’t even have any words in it. WB

Rising Stars: New Young Voices in Poetry by Ruth Awolola, Victoria Adukwei Bulley, Abigail Cook, Jay Hulme, Amina Jama (Otter Barry)

Highly commended in this year’s Centre for Literacy in Primary Poetry Award (CLiPPA), this anthology, commissioned by Pop Up Projects with help from SLAMbassadors, comprises five poets drawn from the spoken-word community. There are poems about space and aliens, superpowers, animals and the natural world, accompanied by witty and appealing illustrations, and tackled with a delicious energy and freshness of approach: ‘Lost leaves at winter / find their way back home / like a dormant Lego piece’ (‘Spring’ by Amina Jama). The everyday – tea, pockets, kitchens – is written with a tremendous sense of musicality and play, but the anthology’s real trick is the power of its poems about community, bravery, discrimination. Poems like Victoria Adukwei Bulley’s ‘This Poem Is Not About Parakeets’ carry a strong message of tolerance and understanding, but are never preachy. A timely and well-presented selection for children that grown-ups, too, would do well to dip into. JC

The Republic of Motherhood by Liz Berry (Chatto)

Liz Berry’s poems conjure up the juxtapositions and contradictions of new motherhood in a visceral exploration of the exhaustion and triumph of creating another life. From fearful steps leaving a bedroom for two for the last ever time into a waiting car which will return once and forever with three, to the bloodied battles which constitute pregnancy and birth, these are poems which cling to the reader and remain with them like the embrace of a new baby. I cannot read these without hearing Liz’s wonderful voice. They are celebrations of the triumph of motherhood, of a love which defies reason, of the fierce, primal violence of the maternal instinct which is yet the tenderest and gentlest of all emotions. These poems are crafted with a deeply deceptive lightness of touch which only heightens their impact. To say that this was one of my favourite pamphlets of the year is an understatement – it has become in its truth and transcendence one of my favourites of all time. SC

Pamper Me to Hell and Back by Hera Lindsay Bird (Smith|Doorstop)

Pamper Me to Hell and Back by Hera Lindsay Bird (Smith|Doorstop)

If it’s the poet’s job to say which things are like which other things and why, then Hera Lindsay Bird is the CEO of Poem Corp: life is ‘like being given a rare and historically significant flute’; heartbreak is ‘like a tax audit of the soul’. Bird is that rare poet who writes like she actually lives in the era she lives in. More than that, she embodies it. Her poems read like crisis WhatsApp messages from your most internet friends, or would if your friends were all also always-on geniuses. AL

Venus as a Bear by Vahni Capildeo (Carcanet)

Venus as a Bear by Vahni Capildeo (Carcanet)

The winner of the 2016 Forward Prize for Poetry for Measures of Expatriation returns with a visually delightful new collection, tackling a variety of topics ranging from the relationship between humans and animals, to ancient mythology, museum explorations and multilingualism. It is refreshing and compelling to see some influences and marks of foreign languages in an English poetry collection, as it is still not a common phenomenon; here, the interjections in French, Italian, Latin and Icelandic reinforce Capildeo’s acclaim as a global writer. What is most powerful, however, are the reminiscences of her homeland, like ‘Trinidad Sugar’, which not only recounts a very personal story of loss and gain, but also revisits the historical narrative of the author’s origins. ML

Any Change? Poetry in a Hostile Environment edited by Ian Duhig (Strix)

Any Change? Poetry in a Hostile Environment edited by Ian Duhig (Strix)

Any Change? Poetry in a Hostile Environment, edited by Ian Duhig, is a modest (in size, certainly not in spirit) anthology published with the financial support of the Forward Arts Foundation in reaction to the Windrush scandal. It interrogates the growing indifference of the British government towards the immigrant communities in need, as well as the deteriorating state of this country’s social care. What is special about that collection is the range of authors that it brings together, from internationally recognised writers to amateur poets just starting their journey, for whom poetry has become a way out of the reality of racism, homelessness, mental illnesses and impoverishment. This is precisely what makes Any Change? so important right now: it is not restricted to tackling the issue of social disadvantage from distance; instead, it gives voice to those who suffer from it, makes them visible and present in the general discourse and allows them to transform it with their own narratives. ML

Their Lunar Language by Charlotte Eichler (Valley Press)

Their Lunar Language by Charlotte Eichler (Valley Press)

Their Lunar Language is a condensed and successful debut. Eichler’s poems revolve around dichotomies, focusing particularly on the dividing line between the human and the natural, which sometimes is blurred and mitigated, and at times, contrarily, augmented through powerful portrayals of the foreignness and disparity of the two worlds. ‘Trapping Moths With My Father’, to me one of the best pieces, compellingly represents how approaching the realm of nature and glimpsing the other side, which will never be fully accessible, actually reinforces and tightens the bonds between people. Eichler explores that connection in diverse forms, never settling for a fixed stance; she shows us half-complete transformations and immersions into the wilderness, like in the ‘Balloonist’. But among these metaphysical explorations, Eichler also manages to convey the simplicity of human relationships, as in the picturesque ‘Halfway to Voronezh’, perhaps the most tender and personal poem in the collection. The universe the author paints in Their Lunar Language is sometimes obscure, sometimes unsettling, but her poems are nothing less than pure expressions of beauty. ML

Passivity, Electricity, Acclivity by Ella Frears (Goldsmiths Press)

Passivity, Electricity, Acclivity by Ella Frears (Goldsmiths Press)

Combining the pull of story and the shock of lyric with the argumentative precision of an essay, Ella Frears’ pamphlet-length hybrid poem lands squarely in the sweet spot between forms, between art and life, between the long view and the moment. It’s an exhilarating, gripping, hold-your-breath fifteen minutes of reading that somehow pulls everything together and everything apart. AL

The Built Environment by Emily Hasler (Pavilion)

The Built Environment by Emily Hasler (Pavilion)

Reading The Built Environment I had the sense of watching something being brought into being, of being present during its construction. By the poem’s end the scaffolding has been packed away, the wires tucked in, and the structure is absolutely sound, and I’m left with the feeling of a secret, have seen the work and material and skill that went in. These are poems of our natural/unnatural world in all its industry: of bridges and fields, tideline and train-tracks, and, addressed with such adoration it makes you envy it, the river’s ‘clear curve’ in which the speaker swims ‘as long as I could bear . . . muddy-shored, grass / fuzzing edges, trees that overreach // and vibrate with reflection’. MS

American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin by Terrance Hayes (Penguin)

American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin by Terrance Hayes (Penguin)

American Sonnets reminds us of the activist power of poetry, of its impact in times of political trouble, of how we need words to believe in days of ‘fake news’, ‘post truth’ and worse. As 2018 creaks to its end with chaos in Westminster, the ugly undertones of Brexit and its toxic messages of isolationism, closed doors and borders, Hayes has created a post-Trump collection of supreme impact. Cloaked in the guise of love poems, these sonnets avoid easy assumptions and lazy cliche by exploring the contradictions of our times with vivid language and images which roam from the body politic to the body of a lover to the body of state and ‘Mr Trumpet’ himself. Hayes wrestles with the pain of loving his country and yet wanting it destroyed. It is a collection for our era, which has the resonance and weight to remain timeless for generations to come. SC

Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God by Tony Hoagland (Bloodaxe)

Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God by Tony Hoagland (Bloodaxe)

Here, Hoagland proves his mastery of tone, voice and imagery through splendidly candid poems that manage to trouble and amuse, in equal measure, whilst embodying a scathing social commentary of Trump’s America. For instance, in the title poem, the speaker turns off the radio in order to make up his own news reports: ‘Unidentified Rich Man Elected President; / San Francisco Yoga Tragedy: Three People Hugged to Death; / Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God’, are some of the imagined leading stories. In the poem ‘Achilles’, the Greek warrior is a cancer patient in hospital, ‘IV bags suspended over his head / like toy Mylar balloons fastened to his arms by string. / Anyone can see he’s done’. But the speaker wants to say: ‘Look, don’t pity him! His imagination is not dead!’ In turning their bleak reality into a sharp-witted examination of both the self and others – via the saving grace of humour – Hoagland’s poems serve as the ouroboros of contemporary poetry, in which there is to be found both catharsis and an extraordinary affection for the world. ED

Isn’t Forever by Amy Key (Bloodaxe)

Isn’t Forever by Amy Key (Bloodaxe)

Dreamlike and gloriously textured, Amy Key’s Isn’t Forever is a talismanic book of treasure and tenderness. Nowhere more than this excellent book do I find such achingly accurate images of how loneliness feels, and where the proofs against it – though often slant – might be found: ‘to walk in woodland the colour of internal organs’; to try to outrun the ‘peel of the waves’ which are ‘uncooperative’; to bathe, to make a bower or boudoir. The voice here is immediately recognisable, opulent, and simultaneously confiding in its intimacy and deflecting in its self-preservation, an impressive control that belies the pliability of periwinkle bath salts, pearl, perfume, rabbit-fur, rosewater and silk. MS

Us by Zaffar Kunial (Faber)

Us by Zaffar Kunial (Faber)

Us is a perfect title for this collection of poems which seem to speak to each other across the pages. There is a sense of comradeship between them on many levels; from the novelists both quoted and referenced – Ishiguro to Austen, Dickens to Brontë and Mary Shelley to Kureishi – to the repeated murmurs of childhood memories, of fathers and of being the keeper of more than one language. The poems travel from Kashmir to Birmingham, cricket pitches to Constantinople; part of Zaffar’s talent is to take us with him on each of these deep and illuminating journeys. One of the joys of the collection is the diversity of form used and his dedication to employing it with a light yet impactful touch. Zaffar is a joy to read. SC

The House with Only an Attic and a Basement by Kathryn Maris (Penguin)

The House with Only an Attic and a Basement by Kathryn Maris (Penguin)

Kathryn Maris’ third collection is concerned with interiors and exteriors: with, on the one hand, the insides of people’s minds and relationships, and on the other, the jittery and not-entirely-convincing performances they put on for the world. Her characters’ internal drives and neuroses, diagnosed in the language of Freudian psychoanalysis, are stated as plainly as their actions. This even-handed approach to the life of the mind and the life of the world eerily exposes the way that every encounter, whether mundane or fantastic, involves the complex psychologies of two (or more) people scheming, performing, battling, hurting and wanting. AL

The Triumph of Cancer by Chris McCabe (Penned in the Margins)

The Triumph of Cancer by Chris McCabe (Penned in the Margins)

2018 was yet another prolific year for Chris McCabe, with Daedalus, a novel taking up where Ulysses left off, and The Practical Visionary, a collaboration with Sophie Herxheimer responding to William Blake poetically and visually. He also published his fifth collection of poetry, The Triumph of Cancer. It’s a collection that’s as bold and personal as its title suggests, containing elegies for his father and explorations of loss and illness, interweaved with history, modernity and politics. It’s a powerful and emotive read, and is shot through with McCabe’s relish of language and syntactical playfulness. The last line of the collection starts with ‘Flick light, light flicker’, and ultimately this collection is a flicker of light – vulnerable, but also illuminating and hopeful. JC

Anomaly by Jamie McKendrick (Faber)

Anomaly by Jamie McKendrick (Faber)

Anomaly is an elegant, cosmopolitan collection, a citizen of the world that despite its linguistic self-assuredness never takes the opportunities of that world for granted. There is, already, a sense of elegy and admonishment, that McKendrick is resentful of the borders that restrict movement, of toxic flags, of expired empire. ‘[N]o door’, he says, ‘Or if a door an always open door.’ In this ‘home for wandering voices’ he crosses lines, collapsing a busy road to stand with the horses in the field opposite, to draw our attention to treasure: quince from ‘the steel sunlight of Toledo’; inks and paints from India and China, and translations of Magrelli, Machado, Anedda, Palazzeschi, Baudelaire, twinning distant towns and voices in this intricate and readable collection. MS

Working Class Voodoo by Bobby Parker (Offord Road Books)

Working Class Voodoo by Bobby Parker (Offord Road Books)

How many ways are there to damage a man? Emotional repression. Toxic masculinity. Drug use and withdrawal. Capitalism. An individual’s behaviour over time. Lack of money. Lack of attention. Lack of anything to do. It’s all here, ranged line by striking line over emotional distances so quickly and brutally cut across that I felt like I might throw up from the g-force of the currents I was being drawn through. Working Class Voodoo is the closest a book of poetry has ever come to the feeling of being completely immersed in the full-blown adrenaline-flood of an episode. There is an achieving stability here as well, but it is a painful process, and it leaves scars. How beautiful they are too. WB

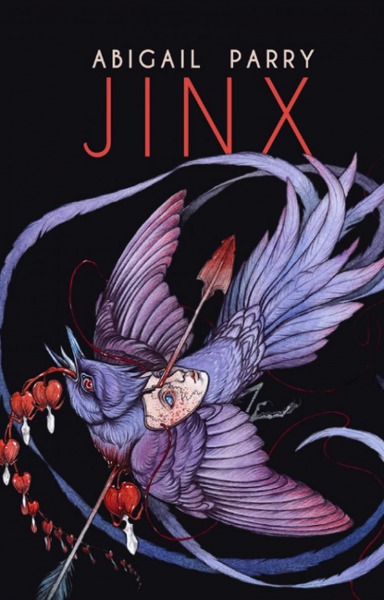

Jinx by Abigail Parry (Bloodaxe)

Jinx by Abigail Parry (Bloodaxe)

Nominated for the Best First Collection at the Forwards, Abigail Parry’s Jinx is as hard to summarise as the slippery definitions of its title, summoning up superstition, folk-tales, spells and childhood games. The poems slide like the ball-bearings in one of those games, but always moving by design (Parry used to be a toymaker – do you see where I’m going with this?) and when she chooses to, she can drop one of those ball-bearings into its slot with a satisfying and stomach jolting thunk, as in the ‘giddy vertex’ of ‘The Knife Game’, the visceral and emotional gut punch of ‘Arterial’ and the shimmy and sway of Ropey Joe in ‘Girl to Snake’. Jinx is packed with intricate and delicious language; it delights in wordplay and in the savour of syllables. As you reach the end of its labyrinthine routes, as ‘The Great Escape’ says, there will be ‘static, click. And play again.’ JC

Feral by Kate Potts (Bloodaxe)

Feral by Kate Potts (Bloodaxe)

In the long-awaited follow-up to 2011’s Pure Hustle Kate Potts further explores her fascination with language and its effect on us. From the otherworldly definitions of animals and objects in the sequence ‘from A General Dictionary of Magic’ to a vocalised electronic dictionary in ‘The Blown Definitions’, an extract from a play for voices, her linguistic exuberance moves into new narrative and emotional territories. The images are always arresting and Potts has a skill for turning the everyday and familiar into something unique and freshly coined. ‘Still yourself; hold your breath’ and revel in it. JC

Natural Phenomena by Meryl Pugh (Penned in the Margins)

Natural Phenomena by Meryl Pugh (Penned in the Margins)

This collection reverberates with overlapping waves of physical detail of the things we miss a thousand times a day, contrary thoughts, and passages that become haphazard, twisted, hardscrabble, ingrowing. What is most remarkable about Meryl Pugh’s Natural Phenomena is its one-pointedness, how the author brings it all together. The sheer sweep of this book, and Pugh’s obsessive control of every single sound and image, endures because it unifies, finds fatbergs and smoke-filled cafes kindred with greenbelt, river, tree, sky. I mean, just listen to this exquisite hoard, the first line of the book: ‘Ash grotto, rain hill, fallen night labyrinth; / demolished Palace, diminishing; / remember-ruin, ripped, deface; / repeat in slow motion your razed / echo.’ We are our attention; make it count. WB

Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting by Shivanee Ramlochan (Peepal Tree)

Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting by Shivanee Ramlochan (Peepal Tree)

Shivanee Ramlochan’s Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting was one of the most electrifying books I’ve read in a number of years; a feeling only furthered by hearing her read from it at this year’s Forward Prizes. Across three sections, the book explores Trinidadian identity through folkloric traditions, religious rituals, shared traumas, the language of ‘speculative fiction’, visceral acts of violence, and a panoply of dynamic, non-binary, and radical-feminist voices. The force with which Ramlochan writes is astonishing, the anger and bravery of these poems often leaving me breathless. The book’s central section – ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, a powerful sequence on rape survival – works to forge a new linguistic space where such inarticulable experiences can be expressed and, in so doing, reclaims these moments for their survivors and stands as a furious condemnation of systematic patriarchal power abuses. The book’s final lines offer a perfect snippet into the justified and uncompromising anger of Ramlochan’s speakers, and the retribution these poems herald: ‘You tell him / I am the queen / the comeuppance / the hard heretic that nature intended’. AP

Rabbit by Sophie Robinson (Boiler House)

Rabbit by Sophie Robinson (Boiler House)

A virtuoso book, uncovering, recovering, and examining the pains and concerns of self-isolation, desire, shame, sex, relationships and false standards in modern society. These poems have an outstanding ear for the ways in which we hurting ourselves as a way to let out the aggression in us. Much like its brilliant faux-fur wraparound cover, this book fucks with expected form, is neither wholly soft nor angular, tossing the usual literary defaults for dealing with such issues into the incinerator and then watching to see whatever remains rise from the updrafts. It moved me to tears. I felt physically weakened by it (whilst it simultaneously forced me to reconsider what I or our culture might consider as ‘weakness’ at all). I am profoundly grateful so have experienced such a new way of writing about, through, and deeper into those insecurities. WB

Soho by Richard Scott (Faber)

Soho by Richard Scott (Faber)

Rarely has a debut collection arrived so fully formed, accomplished and exciting. Rightly shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection, Scott is a poet whose deft control of his subject matter enables him to tackle him the inheritance of shame and its influence on the life of a gay boy and man. I like nothing more than echoes of a couple of thousand years of poetic allusion and Scott clearly delights in his forebears, from Verlaine to Donne to Whitman, either explicitly or obliquely, both in form or credit. Soho is a joy, like Richard himself, an exuberant, courageous, honest triumph. SC

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith (Chatto)

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith (Chatto)

Technically, we already included the 2017 American edition of Don’t Call Us Dead in last year’s round-up, but making a list about poetry in 2018 and not including Danez Smith just doesn’t make sense. It was a book of the year last year, and it’s a book of the year this year: essential reading. AL

Green Noise by Jean Sprackland (Cape)

Green Noise by Jean Sprackland (Cape)

Green Noise pulses, throbs, buzzes and creaks with the footfall of nature and the range of our human interactions with the natural world. Through waters deep or dankly swimmable to dandelions and gall wasps to ‘lost villages’, their memories are as tangible as their stone skeletons and half-remembered names. The joy of reading Sprackland is in her quiet command of form and language, the clarity of imagery and that sense of shared memory, shared experience heightened by a presentation of the known unknown, found again and presented anew. It is a collection which I will treasure. SC

Three Poems by Hannah Sullivan (Faber)

Three Poems by Hannah Sullivan (Faber)

Three Poems stood out this year for its cleverness, confidence and clarity, as well as a fourth C, its undeniable coolness. Determinedly marketed as a successor to T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, these three pieces suggest to me something far more recognisably female, exploring the risk and exhilaration of arrival in a new city as a young woman, and the freedoms and disenchantments of that dislocation. I am impressed by poems two and three, which are quieter, sensitive to the ecstasy and cataclysm of family life. My favourite, though, is ‘You, Very Young in New York’, whose extended lines are long views between tall buildings, and the proliferation of proper nouns, the richness and exuberance of that detail – Bowie, Brachetto d’Acqui, Bidart, Craigslist, Club 19, Krušovice, Camel Lights, ‘Crazy in Love’ – brings Sullivan’s work to vivid life. MS

The AQI by David Tait (Smith|Doorstop)

The AQI by David Tait (Smith|Doorstop)

The AQI is filled with many excellent poems, on subjects such as air pollution and city life, but I’m going to focus on just one worth the cover price of the book alone. The centrepiece of The AQI – ‘After Orlando’ – is about the 2016 shooting in which forty-nine people were killed at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Florida, the deadliest mass shooting in modern US history. Its balancing of extraordinary mourning and white-hot fury is astonishing, as it carefully intercuts and dissolves frame by frame (in ascending order of heartache): Shakespeare; personal and/or imagined reminiscences of anti-LGBTQ+ abuse; transcripts from those who survived; texts of those who were killed; a list of every single person murdered at the shooting, including full name and age, in alphabetical order. It is a engrossing, exhausting protest against forgetting, unbearably sad, but a sadness that by turns will make you more aware, attentive, alert, alive, aglow. WB

The Barbarous Century by Leah Umansky (Eyewear)

The Barbarous Century by Leah Umansky (Eyewear)

The big-budget TV serial has become a force to be reckoned with; box-sets and binge-watching are common currency, and the advent of streaming services has changed how we engage with long-form storytelling. Poetry is never far behind, treating these stories as another way of engaging with our physical and emotional landscapes; The Private Press produced a chapbook on Twin Peaks (the original must-see series) and Nine Arches published Roz Goddard’s The Sopranos Sonnets. The central section of Leah Umansky’s The Barbarous Century, titled ‘People Want Their Legends’, hones in on Mad Men and Game of Thrones, drawing out their profundities in poems that are cautionary, educating, politicising and entertaining. Umansky’s skill is in directly engaging with the world of the show whilst bringing it into our own sphere; ‘Cersei’ is particularly affecting. Throughout, this book expands and contracts, deliberately resistant to pigeonholing: ‘let the gutter turn operatic’, the first poem ends; ‘I will sing of the heart’. JC

Tenuous Rooms / Solo for Mascha Voice by Jack Underwood (Test Centre)

Tenuous Rooms / Solo for Mascha Voice by Jack Underwood (Test Centre)

Every poem is ultimately a love poem, Jack Underwood’s latest collection of poetry seems to propose. And language isn’t always the most reliable system of meaning in conveying the complexity of love, be it romantic or otherwise. In this sense, translation – or the act of translating one’s response to another writer’s body of work – can serve as a focusing device through which the love poem is tackled both conceptually and emotively. This elegantly designed book consists of two sequences of seemingly unrelated poems, which question, celebrate and agonise over the idea of love poetry. If in Tenuous Rooms the speaker embarks on an ingenious attempt to emulate and parody the best-known love poems in literary history – from Dante to Donne to Elizabeth Barrett Browning, in Solo for Mascha Voice, we are taken deep down into the forlorn speaker’s psyche, where the conjured voice of Polish-born poet, Mascha Kaléko, resonates with so many unpredictable responses. It’s a supreme love for poetry that calls forth both sections of Jack Underwood’s new volume, and, in conjunction with it, the reader’s awe and admiration. ED

Longlist

A Quarter of an Hour, Leanne O’Sullivan

American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin, Terrance Hayes

An Ocean of Static, J. R. Carpenter

Anomaly, Jamie McKendrick

Any Change? Poetry in a Hostile Environment, ed. Ian Duhig

As Slow As Possible, Kit Fan

A Watchful Astronomy, Paul Deaton

Baby I Don’t Care, Chelsey Minnis

Bezdelki, Carol Rumens

Black Girl Magic (BreakBeats anthology 2), ed. Mahogany L. Browne, Idrissa Simmonds, Jamila Woods

Blackbird, Bye Bye, Moniza Alvi

Blotter, Oli Hazzard

Body Work, Tom Betteridge

Brown by Kevin Young

Cruel Futures, Carmen Giménez Smith

Counter Reform, Charlotte Newman

Dedalus, Chris McCabe

Did You Put The Weasels Out?, Niall Bourke

Don’t call us dead, Danez Smith

Passivity, Electricity, Acclivity, Ella Frears

Electric Arches, Eve Ewing

England: Poems from a School, ed. Kate Clanchy

Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting, Shivanee Ramlochan

Feeld, Jos Charles

Feral, Kate Potts

field notes on a downpour, Nina Mingya Powles

Fondue, A. K. Blakemore

From There To Here, Ciaran Carson

Giant, Richard Georges

Girls are Coming Out of the Woods, Tishani Doshi

Green Noise, Jean Sprackland

Grid, Alice Tarbuck

I can’t wait for the wending, Wayne Holloway-Smith

If They Come for Us, Fatimah Asghar

Insistence, Ailbhe Darcy

Introduction: The Poetry Business Book of New Poets, ed. Suzannah Evans & Peter Sansom

Isn’t Forever, Amy Key

Jinx, Abigail Parry

Knowing This Has Changed My Ending, Alex MacDonald

Like, A. E. Stallings

Milk Tooth, Martha Sprackland

Natural Phenomena, Meryl Pugh

Negative Space, Luljeta Lleshanaku

25, Geraldine Clarkson

Not Here, Hieu Minh Nguyen

Now We Can Talk Openly About Men, Martina Evans

Nowhere Nearer, Alice Miller

Oceanic, Aimee Nezhukumatathil

Pamper Me to Hell and Back, Hera Lindsay Bird

playtime, Andrew Macmillan

Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God, Tony Hoagland

Rabbit, Sophie Robinson

Registers of Illuminated Villages, Tarfia Faizullah

Rising Stars: New Young Voices in Poetry, ed. Ruth Awolola, Victoria Adukwei Bulley, Abigail Cook, Jay Hulme & Amina Jama

Self Heal, Samantha Walton

Shrines of Upper Austria, Phoebe Power

Soho, Richard Scott

Songs of Love and Horror, Will Oldham

Spells: 21st century Occult Poetry, ed. Rebecca Tamás & So Mayer

Subcritical Tests, Ailbhe Darcy & S. J. Fowler

Suffolk Bang, Adam Warne

Support, support, Helen Charman

Tenuous Rooms / Solo for Mascha Voice, Jack Underwood

The AQI, David Tait

The Barbarous Century, Leah Umansky

The Built Environment, Emily Hasler

The Caught Habits of Language: An Entertainment for W. S. Graham on his Having Reached 100, ed. Rachael Boast

The Death of a Clown, Tom Bland

The Displaced Children of Displaced Children, Faisal Mohyuddin

The Distal Point, Fiona Moore

The Games, Harry Josephine Giles

The Geography of Rebels, Maria Gabriella Llansol

The Healing Next Time, Roy McFarlane

The House with only an Attic and a Basement, Kathryn Maris

The Illegal Age, Ellen Hinsey

The Jude Poems, Matthew Halliday

The Maldon Aviator, Richard Skinner

The Möbius Strip Club of Grief, Bianca Stone

The Moon Is A Pill, Ausra Kaziliunaite

The New Testament, Jericho Brown

The Perseverance, Raymond Antrobus

The Practical Visionary, Chris McCabe & Sophie Herxheimer

The Republic of Motherhood, Liz Berry

The Triumph of Cancer, Chris McCabe

Their Lunar Language, Charlotte Eichler

Threads, ed. Sandeep Parmar, Nisha Ramayya & Bhanu Kapil

Three Poems, Hannah Sullivan

Tiger, Rebecca Tamás

Truffle Hound, Luke Kennard

Unwritten: Caribbean Poems After the First World War, ed. Karen McCarthy Woolf

Urn & Drum, Lila Matsumoto

Us, Zaffar Kunial

Venus as a Bear, Vahni Capildeo

Waitress in Fall, Kristín Ómarsdóttir

Wake, Gillian Allnutt

Wade in the Water, Tracy K. Smith

When I grow up I want to be a list of further possibilities, Chen Chen

Who Is Mary Sue?, Sophie Collins

Working Class Voodoo, Bobby Parker

Wretched Strangers: Borders Movement Homes, ed. J. T. Welsch and Ágnes Lehóczky

I can’t believe Carrie Etter’s ‘The Weather in Normal’ is nowhere. It is a sutble, innovative exploration of the personal and political — family, climate change and the fundamental importance of place to identity and humankind. A disappointing and surprising ommission from your list — not even on the longlist?

HI Jinny – the list very much impartial. We love Carrie, but we haven’t found time to read her book yet. So we very much welcome suggestions from our students!

Will not sure how to contact you but i have dome many poetry courses and uploaded poems and some of them I would like to download again from the library on my part of the site .is there a way of doing this? regards justine newport